The only rules worth following are the ones you write yourself.

Very few companies understand the big idea behind their brand, if they even have one.

They may know their mission and vision. They may see how they plan to disrupt their space, or have a feel for what the big idea is behind their product, but the big idea behind a brand is something very different.

Your brand’s big idea is a notion or concept that changes the rules for everyone in the space — you, the customer and your competitors.

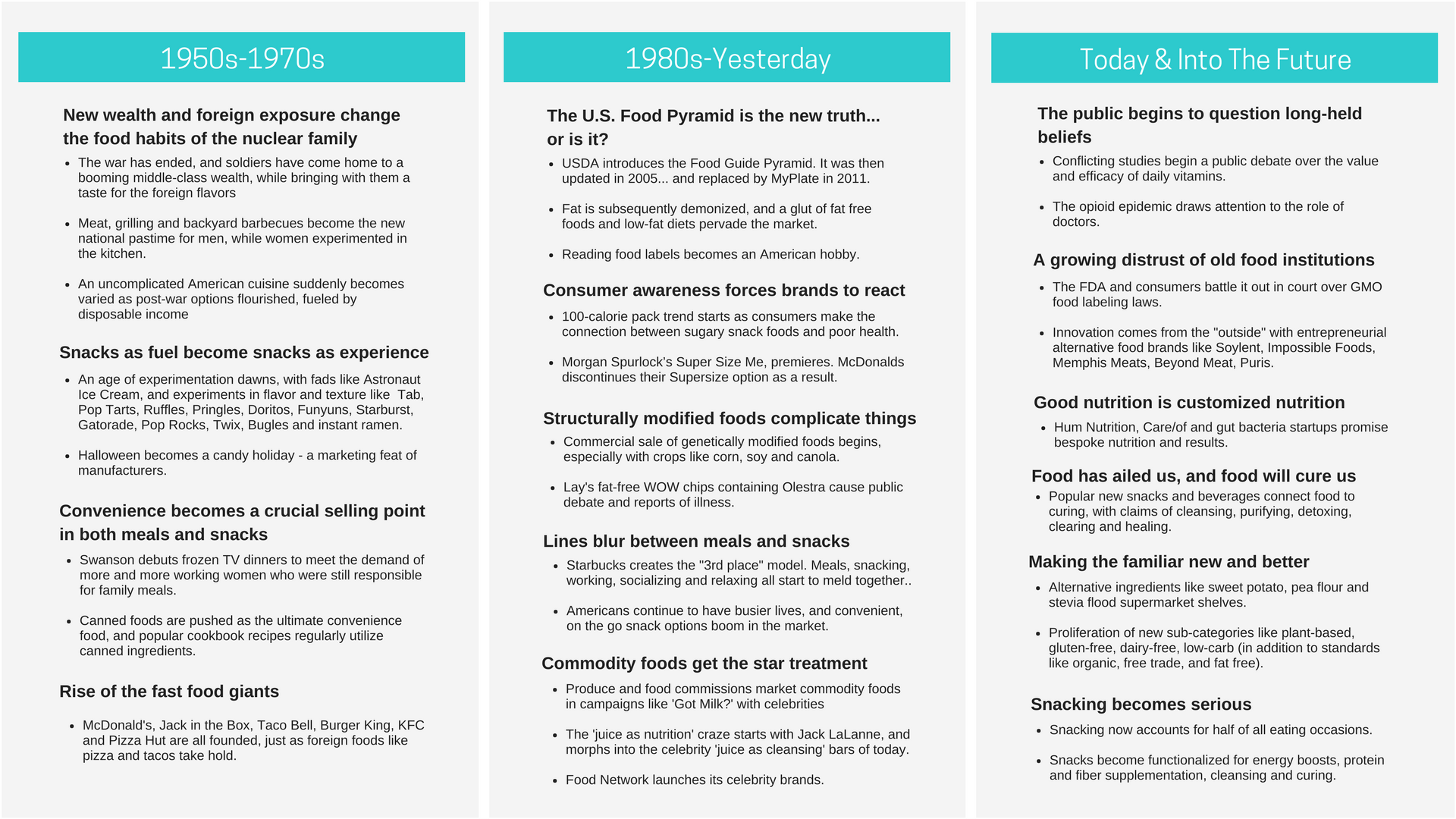

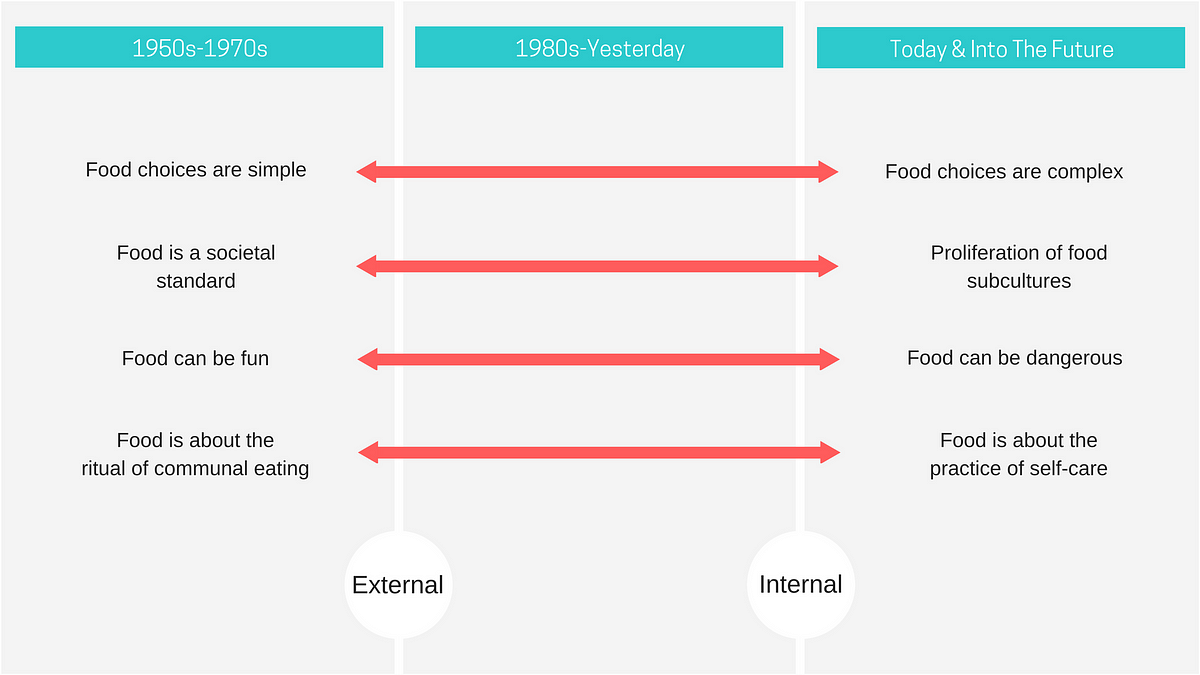

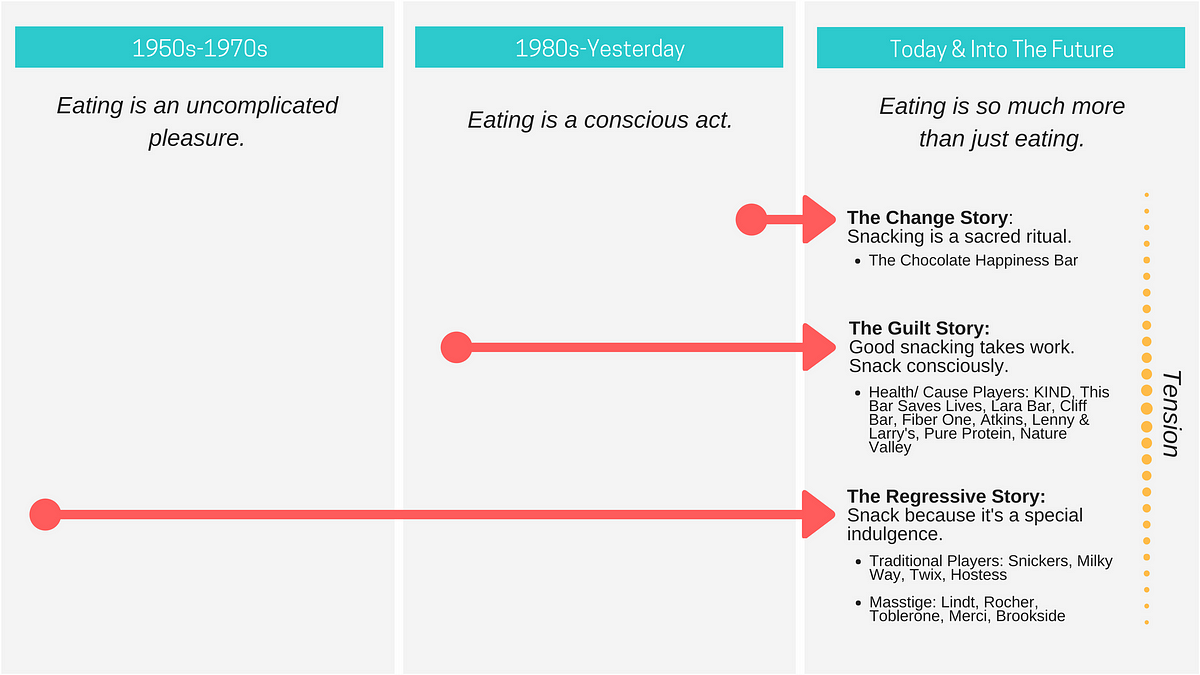

The rule used to be that food programing on television was a specialty genre. Food shows and channels were niche, much like crafting programs or channels centered around sport.

Then 9/11 happened and suddenly people were looking for comfort.

One of the first places they turned to was The Food Network. There was such a huge influx of viewership, that the company chose to rethink the very concept of their brand.

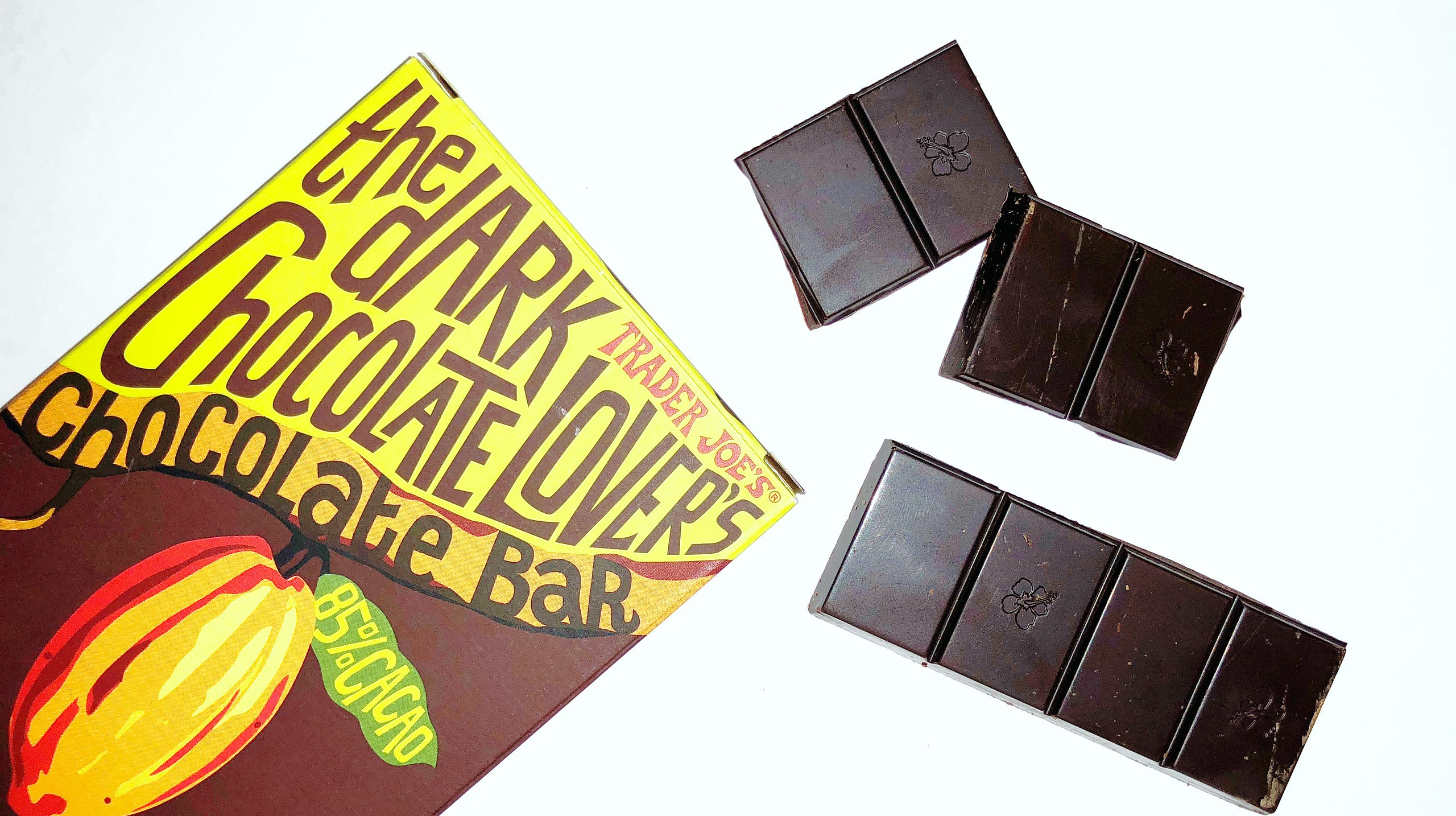

They quickly understood that food didn’t have to be about food. Food could be about entertainment and safety — a notion that was unthinkable even a few months before that point in history.

That’s a huge change in the rules.

When you change the rules, you change the paradigm. The Food Network’s big idea not only affected them, it affected their customers and perhaps above all, affected their competitors.

Alton Brown recalls that time and what it did for the landscape:

It spawned an entire comfort culture that led to the proliferation of experiential wellness and self-care, ASMR and mukbang videos, and hygge, among other things. All ways to shut off our brains and simply absorb feel-good sensory content.

Changing the rules creates a new lens that hasn’t been considered before by the user.

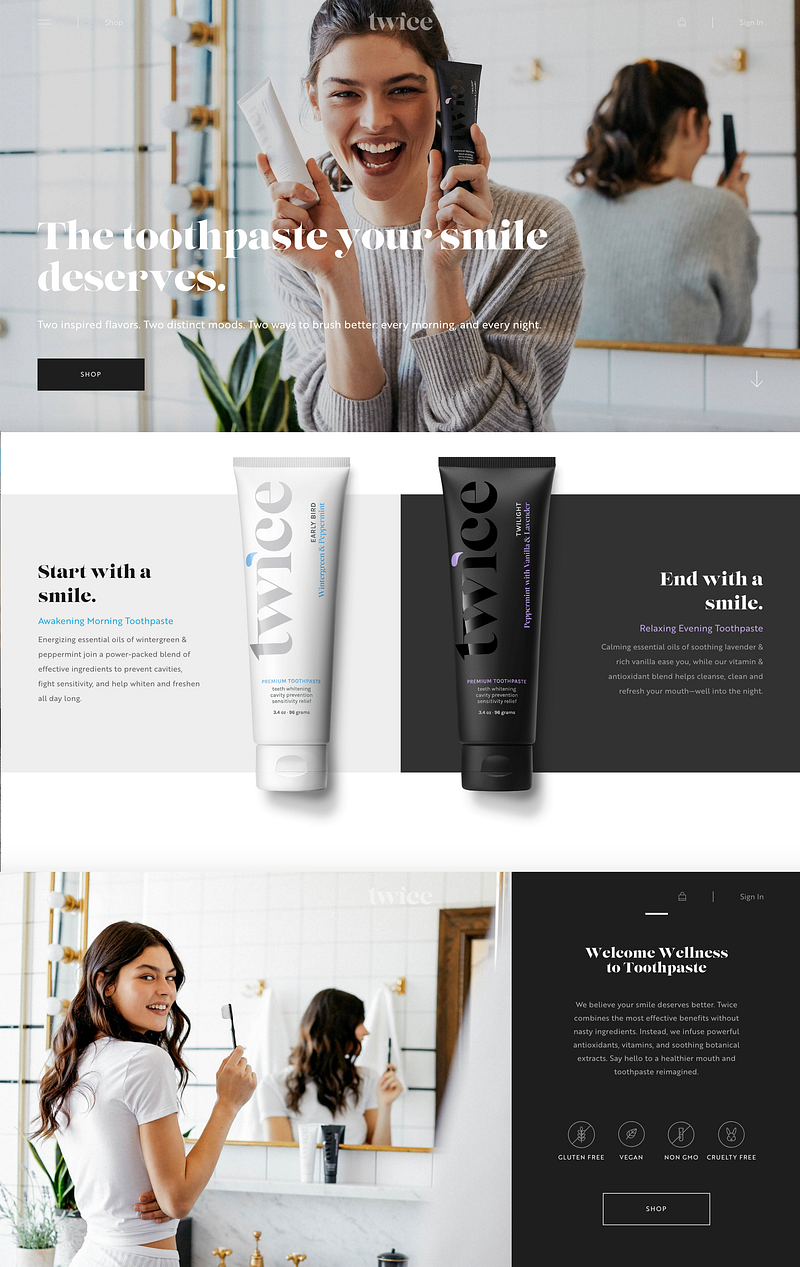

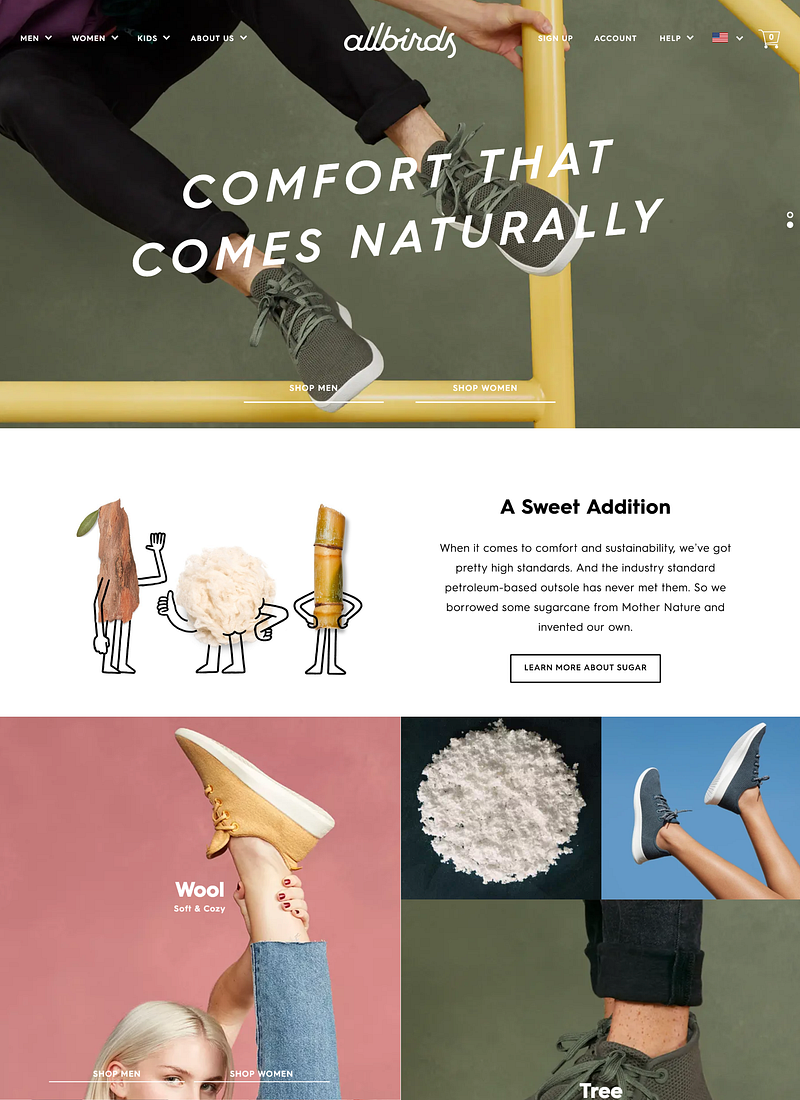

Very few companies today — even many of the buzziest or well funded — have a big brand idea behind them, and that’s because they’re tapping into a rule set that already exists.

Great Jones makes beautiful, affordable cookware that millennials love, but they’re playing by today’s rules of what it means to be a good host and transitioning to an adult life.

They, along with others like Year and Day and Misen, have a huge opportunity to redefine the spaces we eat in. After all, gender roles in the kitchen have changed, this is the first time in history when entertaining a dinner party does not have be precluded by marriage and homeownership, and the role of the celebrity chef has altered our relationship to food altogether.

Any of these new millennial-facing cookware brands could capture the latent value of these cultural shifts by creating a narrative or context to understand them in.

They could write new rules around the intimate act of eating in the home or what it means to reclaim the cooking and eating space that was once so politically charged and gendered, but is now up for complete redefinition. There is room for a brand to lead this conversation and create the new rules of engagement around it.

Instead, they’re playing by the old rule book that Le Creuset wrote decades ago: embody the role of a good host, create something beautiful that guests will remember, and have that picture perfect adult life. Basically the same roles and relationships we’ve had to eating and cooking for a very long time now. The same rules our parents and grandparents operated in.

Brands following someone else’s rules leave money on the table.

They can get very far, and perhaps even win, without a big idea propelling them, but let’s be very clear about what’s really happening here — they’re creating a brand for today, playing by today’s rules and today’s values.

Even though Great Jones and Year and Day both have very specific visual styles and motifs, illicit a general feeling very well, and have seemingly figured out product-market fit, there’s more to be had here.

Those that create a brand for tomorrow by defining a new set of rules and pushing users into that unfamiliar future are far more defensible in the long run because they are creating their own authority and their own playing field.

There is no doubt that The Food Network has benefitted tremendously by spearheading a big idea.

It led to celebrity chef franchises (unlike any we had seen before), food and cookware (both chef-driven and private label), and a major event circuit. This is an entire world of market opportunity that didn’t exist before they changed the rules.

It’s risky but when done right, a big idea with new rules means new market opportunities as well.

If you’re building something meaningful, you need to start mining for your brand’s big idea now. Here’s how to know it when you find it, and how to leverage it to create a whole new roadmap.

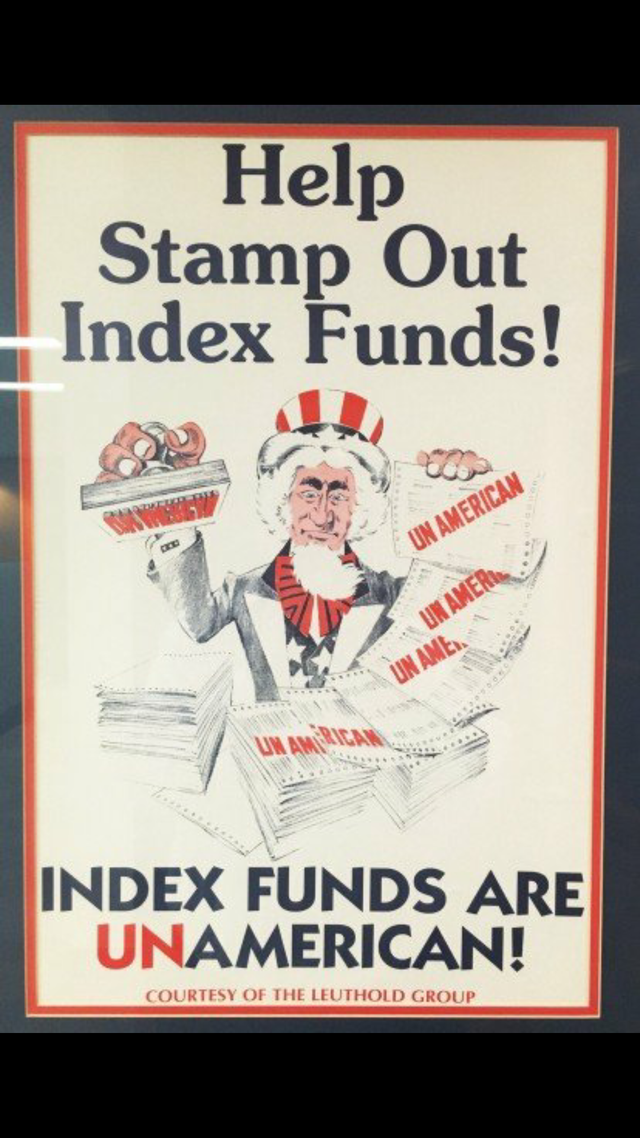

Your brand’s big idea must create new rules that make old norms obsolete.

This is the first sign of a big brand idea.

You’re not just making things better or more advanced in a way that evolves current norms. When you change the paradigm of an entire space, there simply is no room for old norms to exist anymore. You’re creating a whole new reality.

If you take a look at The Cooking Channel, a graveyard for old food programming and spinoff of The Food Network, you can see that these brands literally live in two different worlds.

Every user touchpoint from the videos to the cookbooks and community either falls into the old or new paradigm. A show on The Cooking Channel such as Cook’s Country is not a passive experience, nor does it trigger the same entertainment signals in your brain.

The community that’s formed around the show does not engage the way that you might see around The Food Network, celebrity chefs have very different relationships to their audiences, and the overall experience is wildly different.

You couldn’t even evolve The Cooking Channel’s programs, non-TV content or community to fit into The Food Network. A Cook’s Country chef isn’t going to show up on an episode of Hot Ones like Alton Brown did.

The brands are on two different planes.

Big brand ideas are hard for this very reason — you oftentimes have to scrap everything you know and be willing to build from the ground up.

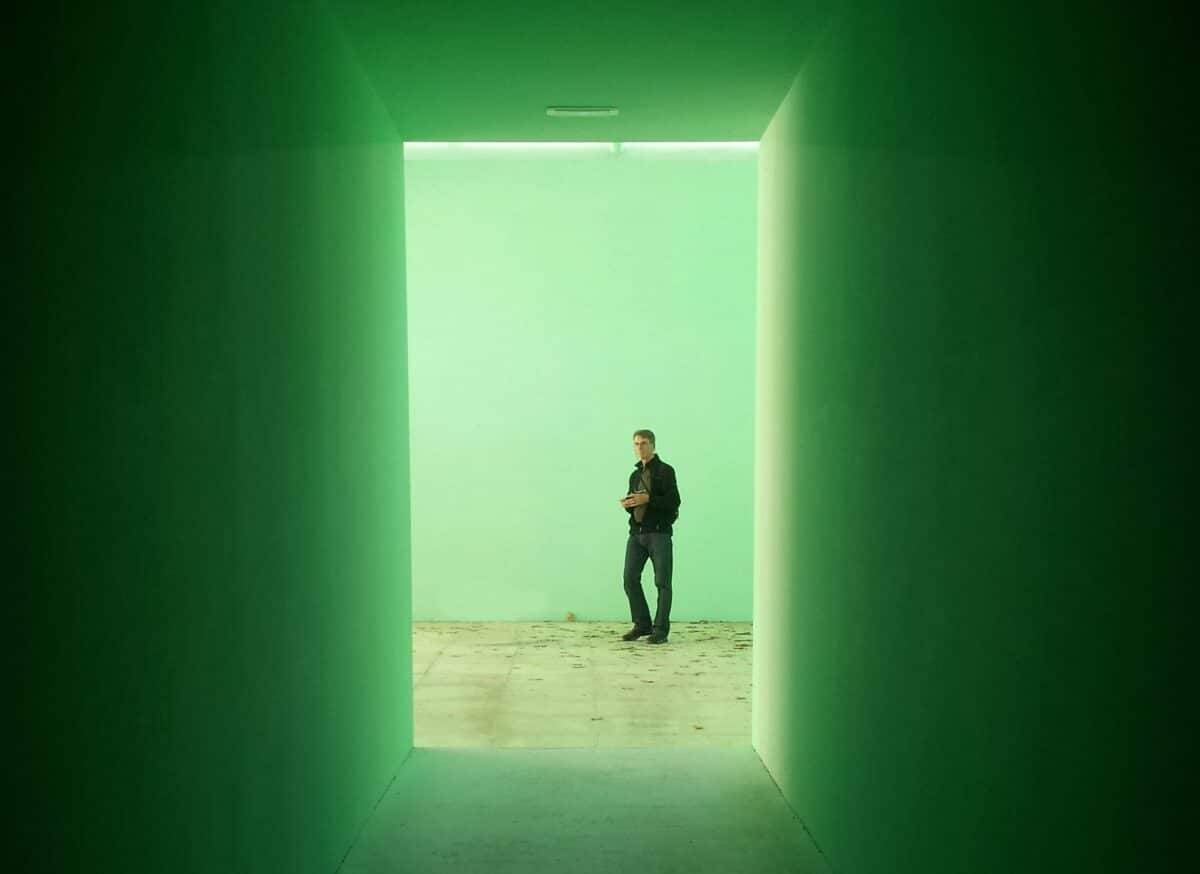

The idea is bigger than the sum of your product and your user. It’s a new lens that changes the way we see (and behave within) the world.

Big ideas are debatable, risky and likely to fail.

Big ideas are not guaranteed to work.

Your audience is always ready to be pushed into the future, but sometimes we push them too hard, too far, or in the wrong direction.

The Food Network’s big idea was highly debatable (especially for its time), risky and likely to fail. But it worked.

Then again, so was Snapchat’s big idea, as I wrote back in 2016:

According to Evan Spiegel, “It’s not about an accumulation of photos defining who you are … It’s about instant expression and who you are right now.” If you think Snap’s new Spectacles product is a misguided step into hardware, consider it from that strategic narrative. Spectacles are about reliving memories, not creating a curated online album like every other social network out there.

Snap Inc.’s strategy created pressure to move into a different market. Killer strategies pressure you to make divisive decisions. They pressure you to change your consumer’s behavior and mindset.

They also pressure you to talk directly to audiences that are on your wavelength, and force you to risk not talking to the rest of the world.

They’ll push you to do the impossible. In this case, that means winning where Google Glass failed, with an arguably simpler product no less.

Snapchat and Google both shared a big idea around how we experience life through AR and shared content.

Neither of them could make it work, but rest assured there will be other companies with other attempts, and each time the big idea will be just debatable as it has been.

That doesn’t mean, however, someone can’t figure it out. It only means that we’ve tried to either go too far, too soon, or in the wrong direction.

Big ideas will open new doors that sound crazy (at first).

Hardware sounded crazy for a social network. Private label goods sounded crazy for a television network. But in both cases it was the big idea that revealed those new market opportunities, and once the gates had been opened, it didn’t sound so crazy anymore.

If your big idea leads you into new categories and products, then you’re likely on to something.

You can think of big ideas — and brand strategies by extension — as master filters.

When you’ve nailed down that big strategic idea, you should be able to filter every choice through it and arrive at an on-brand decision.

Everything from product to communications, customer service, UX, partnerships and collaborations, HR and hiring, executive team, sales, operations, business development… everything should be filtered through your big strategic idea to make sure you are arriving on an on-brand decision.

It is a filter for every choice that matters, and the choices that matter the most are the ones that move you forward in your market.

Use your big idea as a filter for your product roadmap and you may find that the obvious choice for your brand is no longer the right one. Big ideas will move you into weird, scary places sometimes, but that is where the true opportunity lies.

Fewer and fewer companies are winning by staying in their lanes.