What‘s said vs. what‘s heard.

At any given time, your brand is communicating two different stories — the spoken story that you’ve created, and the heard story that the consumer internalizes — and they’re not the same thing.

The spoken story is under your control.

Your history, legend, consumer touch points, language, brand identity, packaging, user experience and so on are all part of the spoken narrative you’ve created.

The heard story, however, is what the consumer actually hears when your spoken story touches them.

Even though that’s ultimately the story you want to influence, you can’t directly control how the heard story is internalized.

Let’s consider a very literal example.

When I say the phrase “That which cannot be named,” where does your mind go?

Do you hear the spoken story of something nameless, formless, blank and full of positive potential… as was intended by this originally Taoist phrase?

Or do you instead imagine something dark, mysterious, looming and threatening? Something taboo and perhaps evil.

Chances are you heard the second version.

In fact, that heard story is so much stronger than the spoken story, that J.K. Rowling adapted it for the character “He Who Must Not Be Named” a.k.a. the existentially evil Voldemort.

That’s how spoken stories and heard stories work.

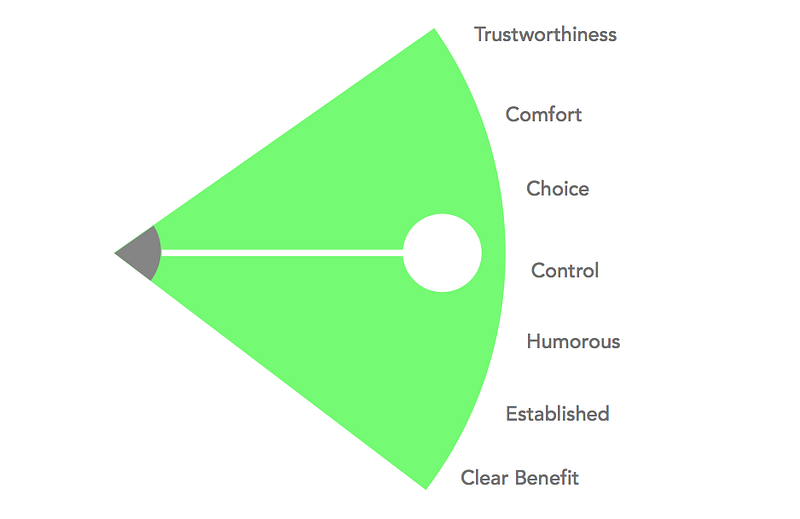

The heard story is usually stronger than the spoken one, and it takes into account a lot more than just what you’re saying.

Just because you’re saying it doesn’t mean that’s what’s being heard.

One of the biggest mistakes a company can make is not knowing which heard story they’re communicating.

There are 2 common types of hidden counterstories — heard stories gone awry — that are important for any brand to be aware of.

1. The Silent Kind

For some brands, the heard story is likely the exact opposite of the narrative they want to employ.

This is especially true with brands trying to address a clear pain point.

Sometimes talking about a solution underscores the hopelessness of the problem instead.

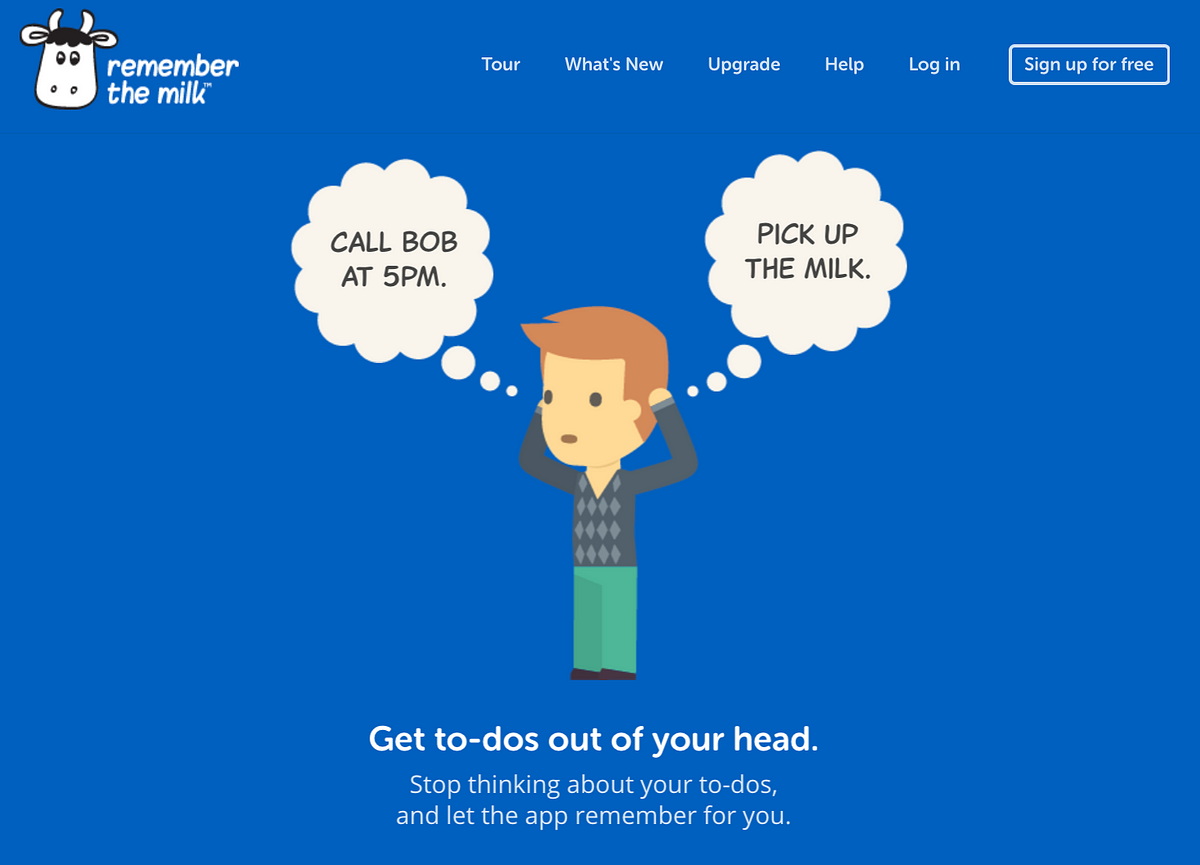

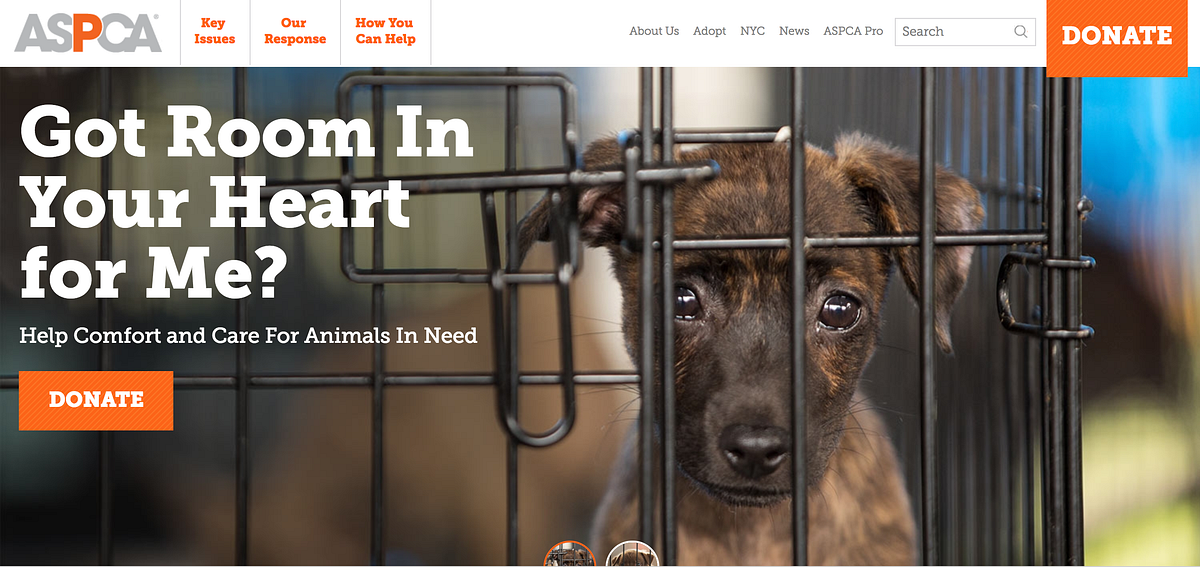

Whether you’re a task app highlighting the overwhelm of daily life, or a nonprofit focused on the suffering of the disenfranchised, what people are actually hearing you say may not be what makes them convert.

Is Remember The Milk telling a story about control… or instead chaos?

Is the ASPCA creating a story of hope… or rather hopelessness?

These silent counterstories are deceptive.

You might think, why shouldn’t a brand explain the problem they are solving?

You can explain the problem you are solving, but that’s fool’s gold at best.

People don’t want to know you can fix their problem. They want to know who they can become with your product.

…and who they can become is much bigger than the problem holding them back today.

“Here’s what our product can do” and “Here’s what you can do with our product” sound similar, but they are completely different approaches.

— Jason Fried (@jasonfried) November 13, 2013

The better version of themselves is the real prize for consumers.

Move past the pain point, or your heard story may backfire.

2. The Tethering Kind

Be wary of any narrative that talks about the “other”.

We see this a lot in politics and the public realm. Notable figures, leaders and sometimes entire nations define themselves as not being the other.

If I mention Israel, you may think Palestine. If I say Aaron Burr you may reflexively respond with Alexander Hamilton (and milk, if you’re an older millennial like me). The thought of Taylor Swift may conjure up Katy Perry.

These are examples of how defining yourself against something will, by definition, wrap that thing into your identity.

Defining yourself as ‘not the other’ will always tie you to whatever that ‘other’ is.

Brands do this all the time.

Anytime a brand is ‘XX% better than’, ‘a newer version of’’, ‘ the most XX’ or ‘not like XX’, it is tethering itself to the very competitor it’s trying to break away from.

You can employ these comparisons to help users make more informed decisions, but they should by no means be your top line message.

Use tethering language very carefully and sparingly, if at all.

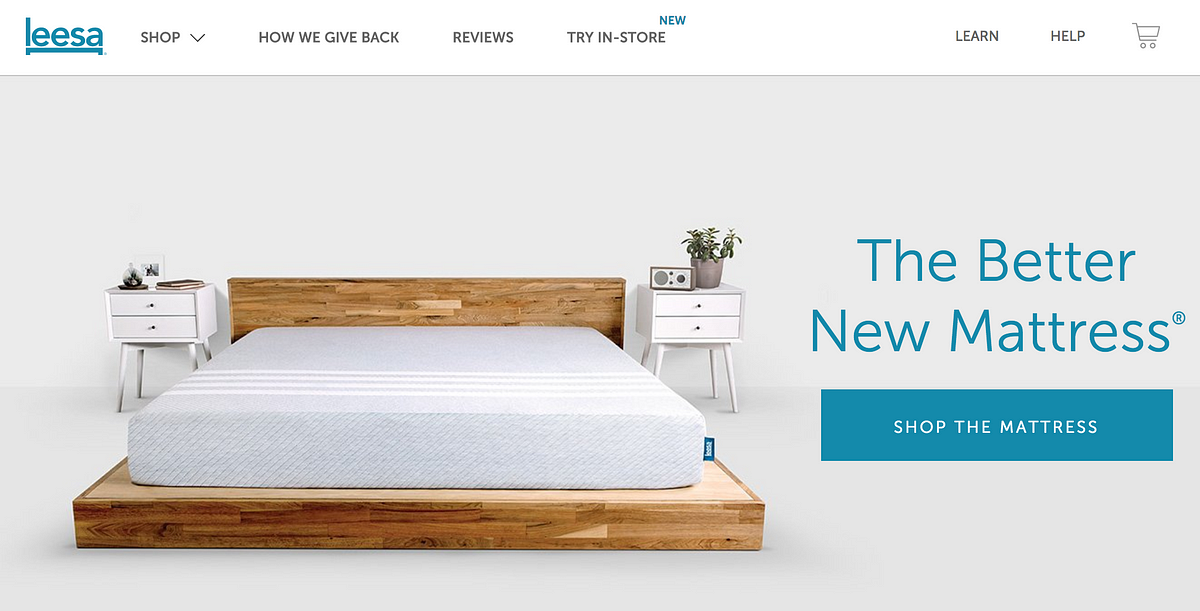

When it comes to commodity goods (such as mattresses) this is especially true.

What is left of the Leesa brand if you take away the “other”?

It’s easy to see the Leesa brand has no legs once the shine of “better new” wares off.

When Buzzfeed recently announced the slogan “All the news too lit for print” for their AM to DM show, it was a clear appropriation of The New York Times’ famous slogan “All the news that’s fit to print”.

The threat of lawsuit quickly forced Buzzfeed to take down the phrase, but it may have been for the best considering how tethered the branding was.

If Twitter is any barometer, it was a poorly conceived idea.

After all, how can you build a meaningful counterculture brand that is so reliant on the traditional institutions it claims to supercede?

Tethering stories may work in the short term, but they will not work in the long term.

If you’re looking to create a lifelong brand that sits outside of your competitive set, you have to resist tethering stories.

Once you’re tethered, it’s very hard to get above your competitor’s story. You’re intrinsically tied.

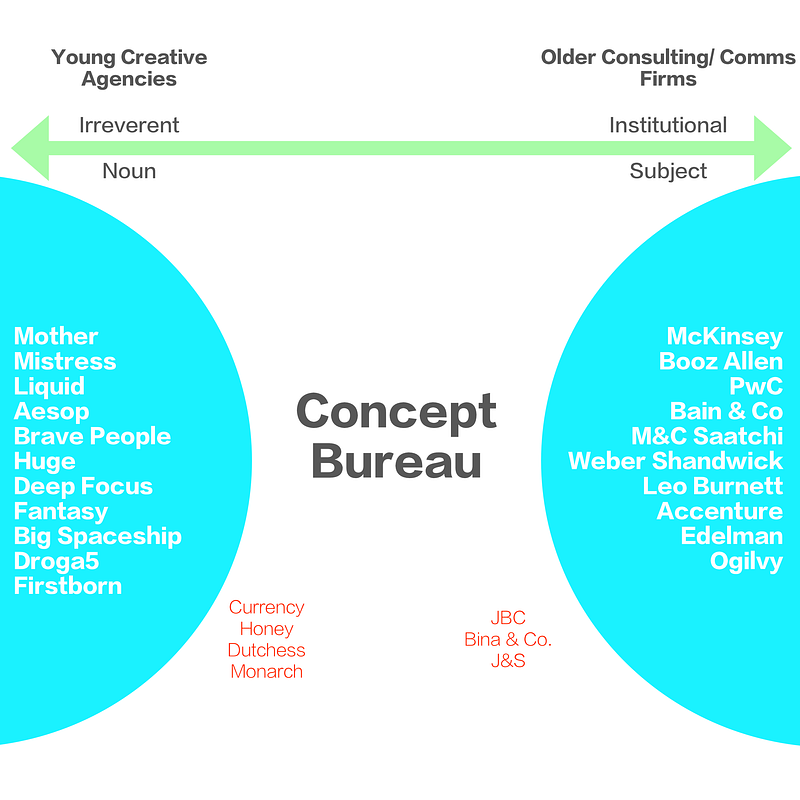

I’ve said before: Better is actually worse. Different is what matters.

Stories that define a different standard rather than a better one will always rise to the top.

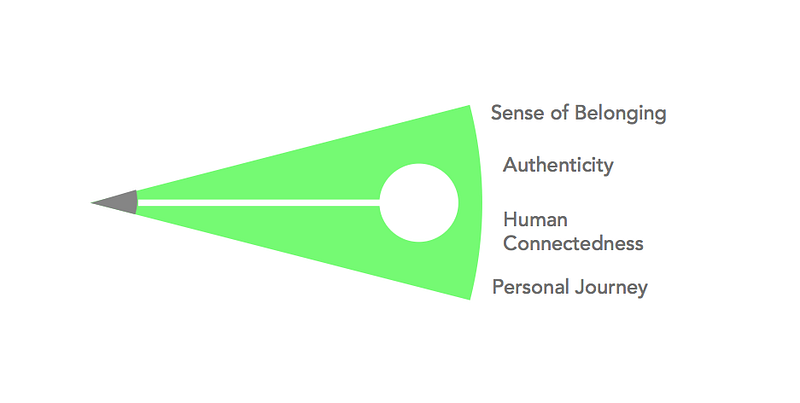

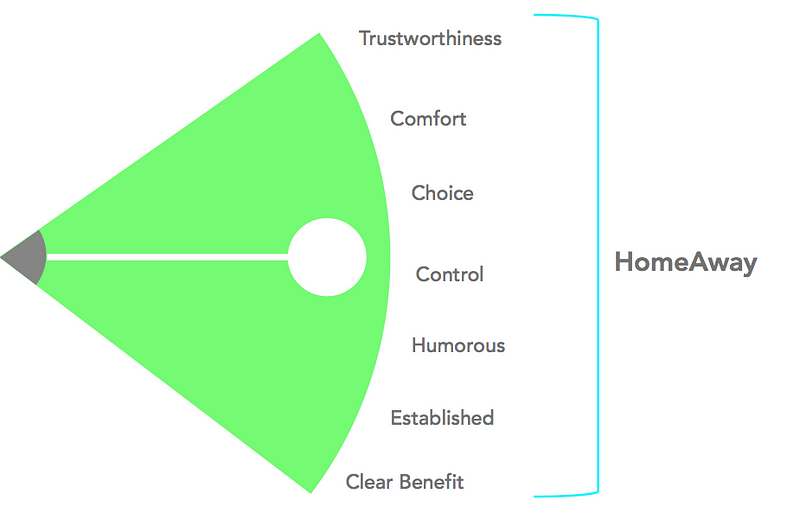

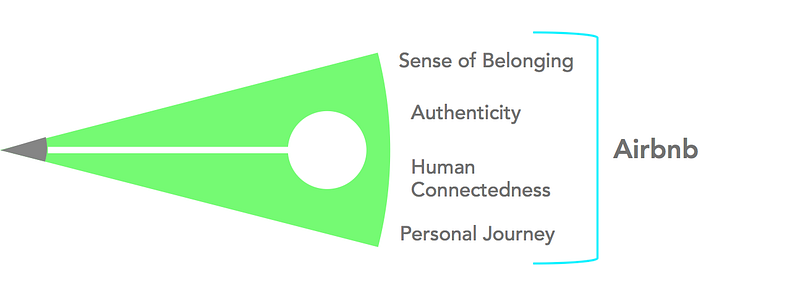

Airbnb isn’t about better accommodations or prices — its about belonging.

The emotional concept of belonging is a dramatically different standard, defined by them, that makes any hotel, hostel or traditional B&B suddenly irrelevant.

Airbnb resisted the tethered story, and it served them well.

If you feel your best brand story is the one that tethers, you’re not trying hard enough.

There is always a larger, more significant story that will push you into less crowded territory.

You can make sure your spoken story and heard story are synonymous, or purposely creating tension by working against (or with) each other, but failing to acknowledge the heard story altogether is almost always a fatal mistake.

What is heard is what matters.

Create the story that you actually mean to tell.