The stories we tell ourselves, both as a group and as individuals, have immeasurable impact on our beliefs and behaviors. Brands trying to reach millennials should know who they’re talking to in this regard.

Every generation has its stories. There was the brave selflessness of the Greatest Generation spanning 1910–1925 (just ask Tom Brokaw, he’ll tell you, but don’t ask 2 Dope Queens), the cautious optimism of the Baby Boomers and the idealistic “just do it” consumerism of Gen X. Millennials, however, stand apart.

Not only do we tell ourselves a greater number of collective stories, but our narratives have become more fragmented as today’s twenty- and thirty-somethings find themselves moving through the in-between spaces of the gig economy, non-marriage and a changing American Dream.

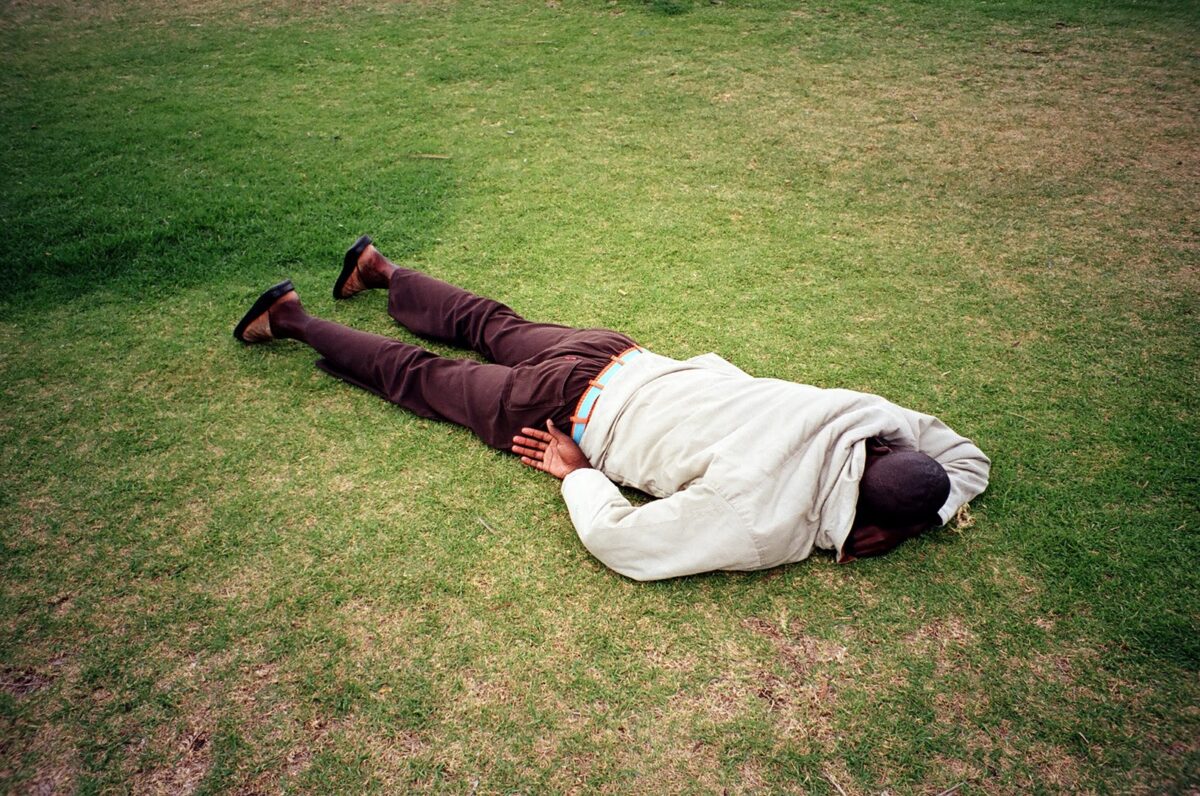

The cemented goal posts of our parents are moving for the first time, and we spend more of our lives between jobs, between adolescence and adulthood, between impermanence and permanence than ever before.

It’s from within those ‘in-between’ spaces that some of our most compelling generational stories have emerged.

Three of those stories — pain, villainy and fuck you money — are actually old stories (even that last one), but perhaps for the first time shattered and put back together in a new form. They matter because they shape us, and since a story reveals just as much about the storyteller as it does about the world, we need to ask ourselves why we created them in the first place.

Perhaps even more importantly, there is no right or wrong. All cultures have a framework for viewing life experiences. These are ours.

Let’s start with the easy one.

Pain — To suffer is to succeed

Familiar with this one? Yeah, me too.

If you’re not suffering, you’re not doing it right. If you’re not working 12-hour days and burned out by Wednesday, you’re not living up to your potential. You’re not doing something worth doing.

Although we may think this is a newly popularized ideal stemming from the sudden rise of entrepreneurship, our Zuckerberg-esque heroes and the glamorization of the hustle we see in movies and content, it’s actually much older than that.

It comes from our puritanical pilgrim roots as Americans, and it was a lot more hardcore back then. It was life-and-death — a somewhat severe focus of Protestant work ethic that neatly parlayed into the pervasive “Manifest Destiny” that shaped so much of who we are as Americans today.

The ideas of pure intention, complete self-sacrifice to one’s service and a god-given edict to tame the land that threatened our lives daily, were all strong forces that never left the American identity. Each of us has played Oregon Trail and watched movies like The Witch. We don’t just get it, we revel in it.

So deep is a story like this, that I’d argue there’s no way to escape it without changing the very fabric of Americanism itself… and that’s not happening. What we have instead is a modern incarnation that every generation before us has morphed into their own, and now we have ours.

Pain happens in the extremes, so let’s look at the extremes to see how we continually perpetuate the pain story.

SoulCycle is about perseverance and suffering, all in the name of getting to the front row. It’s a cult-like, pain-centric movement that mirrors other new, extreme fitness faiths like CrossFit and ultra marathoning.

Elements of bro culture and startup culture overlap with the romanticization of all-nighters and impossible deadlines. WeWork stocks bathrooms and front desks with mouthwash, toothpaste and toiletries while Silicon Valley execs get caught (and sometimes die) using illicit drugs to keep up.

Arianna Huffington has built a profitable Sleep Revolution platform that “sounds the alarm on our worldwide sleep crisis”, and in my opinion, further canonizes the story of pain. Every great phenomenon has its high profile detractors, after all.

But these are all obvious.

There are still different forms of pain to consider. Look at the self-deprivation of The Minimalists and the popularity of Soylent — smart guys telling you how cool it is to give up the comforts of life.

Anytime you see celebs and CEOs relaxing on vacation, it’s simply the other end of the same spectrum. Work hard, play hard. The higher the stakes on one side, the higher they become on the other.

There’s a pattern here. When it’s no longer the elements that threaten us, we seek to develop power of will through extremes. Without a physical frontier to roil against, we create mental ones.

Call it the virtue of turmoil. Nobody likes the love stories that didn’t almost end in heartbreak. I’ve never seen that movie.

The opposite also rings true — it doesn’t count if it’s easy. That’s because we measure ourselves in experiences.

Our self-worth and identity is gauged by what we’ve been through. For millennials, those trials and tribulations are markers of suffering that go beyond what we’ve seen in previous generations. Less from the outside and increasingly from within.

Villains —When heroes become unfamiliar

Think Dexter’s Dexter Morgan, Breaking Bad’s Walter White, or The Sopranos’ Tony Soprano. We didn’t just love them, we identified with them. People mourned Walter’s death with mock obituaries and funerals. It got real.

We wanted them to win. Despite all our cringing and gasping, it felt good when they got away with murder. No matter how conflicted we felt, we quickly resumed rooting for them by the next episode.

These aren’t anti-heroes who lack traditional qualities of valor and moral ascendancy. Nor are they good guys who sometimes do bad things. They’re consistently heartless characters that cause chaos and destruction.

Although there’s discussion on what truly separates a hero from an anti-hero or flawed protagonist in media, it seems we’ve actually started to glorify villain protagonists.

The generation before us had Hitchcock, who deliberately created complex heroes that were hard to love, but that’s as far as it went. Meant to be disorienting and uneasy, Hitchcock’s characters pushed the boundaries, but they never crossed them.

Our millennial characters are different. These are clear villains with harmful tendencies, but if you dig down deep, you see their original motivations are very human and relatable. Walter was the humble, under-appreciated middle class parent trying to make a living. Tony, also a family man, just playing out the only life he ever knew. Dexter living with uncontrollable urges, which he offset by killing bad people.

Our total embracing of these characters creates a new kind of obsessive fandom. These are stories of misunderstanding and gray moral code. Stories of standing on the slippery slope between right and fair. Stories about how, as a post-Hitchcock generation, we’ve learned to make peace with the messy discomfort in this in-between space.

There’s a lot to be said about how socio-economic inequality, eroding faith in public institutions, or a general millennial malaise have created paths to this new character… but there’s more to it.

Every generation has the power to choose what they see in themselves. Baby Boomers saw Superman, Steve McQueen and Bruce Lee — a somewhat mixed backlash to the whitewashed, suburban idealism of their parents.

Millennials continue that shift to a further degree. Heroes, in the traditional sense, stand guard between right and wrong. That kind of black and white life view no longer rings true for us.

I’d argue that a clear right and wrong, at this point, even feels uncomfortable.

We live in the gray area. It’s complicated. It’s polarizing. And it doesn’t form a consensus.

Our heroes are an embodiment of the world we see ourselves in. Not right or wrong, but somewhere in the middle.

Fuck You Money — The formidable task of finding your passion

The most significant story on this list is the quest to find oneself. This one’s a biggie, and I think most of us live within it.

Fuck you money, for those who are unfamiliar, is having enough success and cash to be able to (metaphorically) say “fuck you” to the people who failed, hurt or ignored you along the way.

Up until this generation, success was seen as largely formulaic. Whether that’s true or not is irrelevant. The fact is that there were rules and structures that once existed, and people believed in them. Things like graduate school, babies, the corporate ladder and buying property were inherent truths in and of themselves.

What happens when those things move around or disappear? You get a new story.

For years I fought with my parents about my career ambitions. My father wanted me to become an artist, my mother just wanted me to stop stressing out, but I wanted to be a successful business owner. I went to college, then grad school, then set up my first LLC.

Looking back, that formula was not the best one, nor the fastest, nor the smartest. Definitely not the easiest (and absolutely not the cheapest).

But my career was my life. It was me. When my parents questioned my decision, I felt it to be a deeply personal attack on my identity.

What I didn’t understand at the time was that for my parents, and the parents of most millennials, a career didn’t mean the same thing. Granted my parents are immigrants, but for them, work was a means to an end.

Yes, they wanted to be successful as well, but their jobs had a lot less bearing on their perceived self-worth than it did on me. Work, for them, was something they had to do in order to live their real lives outside the office.

Millennials like me have chosen a different story entirely. Work is synonymous with identity because we believe in a financially post-apocalyptic world that decided to change right before we got here.

Our story is a dramatic, self-important reinvention from the ashes that remain. A survivor story. I believe this too. It frames my good times and my bad times, and lays the groundwork for single-minded career ambitions.

Now that leaves us in a tough position.

Finding yourself and finding your passion are inextricably tied. The pressure to find one’s passion is immense, even though there’s no guarantee this meshing of life and career will make us happier. For many, it can feel like a burden.

It perpetuates the belief that passion already exists within and it’s our job to follow it — a belief that Cal Newport and others have already started questioning.

It’s go big or go home. It’s backpack through Europe to discover your destiny, then come back to America to change the world. It’s do it on your own, like that suffering, solitary hero trying to navigate troubled waters.

I’ve heard enough entrepreneurs and CEOs daydream out loud about fuck you money to realize that for many, this quest is underscored by a sense of comeuppance.

We may not believe that right or wrong exist, or that fairness is a reality, but we do believe in our right to enforce that balance when our turn is up.

Just like the superheroes we created, we deserve to set things straight in our own, deviant way.

The trifecta here, incase you haven’t already seen it, is that all three of these stories fit snugly together. They reinforce each other, and over time become stronger. The virtue of suffering, the villain’s misunderstood journey and the ultimate reward/ retribution flow into each other. Take one piece out and the other two become weaker.

As brands and communities work to engage millennials from the outside, they have to first reconstruct the millennial mindset from the center. What are the stories that make sense of the world we live in? What notions help propel us forward?

Stories help connect the dots, and it’s fascinating to see what narratives emerge when those dots suddenly become mutable. The narratives we tell ourselves today have to wrangle a huge psychographic spread, especially as we mature into the next stage of adulthood.

“Everyone is a hero in their own story”.

That’s one of my favorite quotes. If you consider it from that point of view, everyone makes sense, regardless of age, time or country.