Distinct brand challenges are emerging across every market, and they reveal untapped opportunities for the players that are willing to solve them.

People aren’t buying products anymore. They’re buying brands. That should make you think long and hard about what you’re actually selling.

Even the most mundane of companies — from those that sell toothpaste to those who hawk discount furniture assembly — realize that we are no longer selling goods, features or mere solutions for jobs to be done. We’re selling a story that sparks change in the consumer today, by showing them our brand vision for what the future can be tomorrow.

Some industries have moved forward faster on this than others. Hygiene, beauty, consumer technology and travel have seen huge steps forward in brand ideology. Finance, education and housing, not so much.

On top of these staggered gains hovers a cloud of rapidly changing user behaviors and perceptions.

In beauty, savvy consumers have dramatically shifted from single-brand loyalty to mixing and matching premium names with indie brands. A big part of the beauty experience is now about concocting your own Google-driven regimens.

In finance, peoples’ spending behavior has changed, but new values that pit immediate gratification against future uncertainty have created a tension we haven’t seen before. Brands in this space have done little, if anything, to ease that tension and create a new story around money (which is really a story around success and self worth — two deeply emotional themes).

Even if your brand-leading CPG company has gripped the attention of a lucrative audience, there’s a very good chance you may have educated your consumer past your product.

Specialty diet brands in niches like keto and paleo focus on content in order to build a cult following, but then that content creates a demanding consumer whose tastes quickly evolve out of the brands that sparked them in the first place.

Bulletproof may have opened your eyes to a new narrative around health, but soon enough MCT oils lead to adaptogens and nootropics, and a whole world of possibility that lives outside of the Bulletproof product mix.

Both rudimentary brands and evolved brands face the same problem — the world will not look the same in the near future.

It doesn’t matter how evolved a space is or isn’t. Every category is facing major brand challenges, and these challenges are market-making opportunities for the companies that are willing to solve them.

Below is a high-level rundown of what our agency is seeing in just a few category hotspots. There is a treasure trove of untapped opportunity here.

You may not see your industry on this list, but keep an open mind. Some of the greatest brand innovations have been inspired by outside industries.

You may not be in finance, but perhaps you’re in a space that hits on some of the same emotional triggers. You might not be selling a wellness product, but maybe a wellness story is exactly what can make people more open to trying your product in the first place.

This is not a comprehensive list by any means, but it does cover some of the biggest brand challenges (slash opportunities) we see emerging in the next 2–5 years.

If you move your brand in a direction that solves these challenges, you’ll be poised for major payoff.

Use this as your treasure map.

Cannabis

[Also important for brands that face cultural bias, speak to users that are seeking ‘permission’ to consume/ engage, or are pushing up into new premium levels.]

Brands in the cannabis space, even the great ones like MedMen, are killing it with narratives related to relaxation, stress management and premium fun. But these are the industry’s 1.0 version of benefits.

As cannabis quickly grows up, we won’t be rewarding brands that sell us on benefits. We’ll reward the brand(s) that create a lifestyle.

There is no lifestyle in the cannabis industry right now, save for old cliched relics like the beach bum stoner or high school dropout.

A lifestyle is about values and belief systems, and that matters for the industry because creating a values-driven lifestyle around a product is the fastest way to circumvent cultural biases and fears (of which cannabis will have to contend with as it spreads from early adopters to the masses).

Our parents and neighbors will soon have access to CBD infused drinks, marijuana-laden dishes at restaurants and THC bath bombs, but without a lifestyle narrative, they will not know how to integrate these products into their lives with meaning.

Any brand can convince people to try a CBD drink or pot cookie once. But a very, very tiny fraction will figure out how to make the discerning consumption of these products a lifestyle marker.

The goal isn’t to get your mom to smoke a joint and relax. It’s to make her become a cannabis tastemaker.

(You can read more about the DNA of a lifestyle brand here.)

Healthcare

[Pay attention to this space if your brand is related to wellness or self-care, relies on scientific claims, or stands in the crosshairs between institutions and disruptors.]

Healthcare’s brand is caught between the truth and a lie.

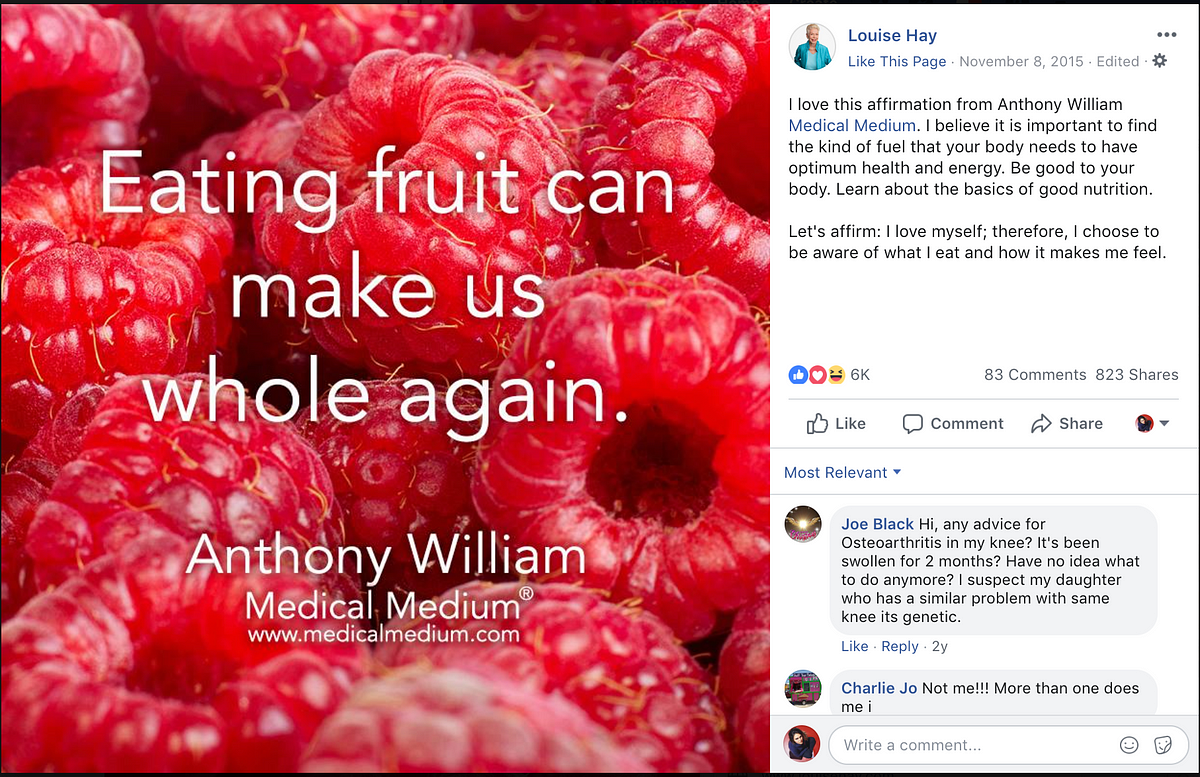

Consumers are exhibiting a growing distrust of old institutions, “disease awareness campaigns” are turning benign conditions like excessive sweating into profitable medical maladies, peer reviewed journals are coming under fire for dubious content, and people like Gwyneth Paltrow and the Medical Medium, for all of their dissenters and critics, are still among the very few voices speaking to fatigued patients with empathy and compassion.

In all of these interactions, our health is constantly being pushed top of mind.

Its spilling into many other parts of our lives as well. No longer is it just under the purview of doctors, hospitals and researchers, but also our personal trainers, our phone apps, our grocery stores, and our Walmarts. It laces the fabric of countless consumer stories.

But all of that information is creating a unique problem.

When people see huge medical advancements on the horizon promising to treat cancer, yet somehow can’t figure out how to turn the results of their gut health testing kit into actionable, measurable lifestyle improvements, the system suffers a significant loss in trust.

All of that frustration and friction is eroding greater brand value.

‘If we’re so close to a cure for cancer, why can’t I make sense of my gut bacteria?’ What many don’t understand is that the perceived failure of that gut health kit is amplified 10-fold by the cure-for-cancer story that’s in the back of a user’s mind.

The fact is that health brands don’t just have to answer to the stories and expectations of their own niche, but those of the larger space as well.

In this case, the expectation isn’t about gut health, it’s about the modern miracles of science. That is the expectation that needs to be addressed and managed.

Even if you’re selling a simple product in this space, remember that it is not only your brand narrative that people are layering over their product experience, but any larger notions they have about healthcare as well.

Startups and old guards need to be far more diligent in mapping expectations and beliefs to actual experience, and to frame those experiences in an empathetic conversation that balances the promise of reaching the pinnacle of medicine with the opacity of how we will actually get there.

Wellness & Self-Care

[Also any brand that relies heavily on consumer education, or is going from niche to mainstream.]

There are a million different messages in wellness and self-care, but the strongest brands have done an excellent job of educating their early cohorts. Most narratives fall in two different camps — those that are empowering and mobilizing, or those that are disempowering and creating fear — and both have engendered sophisticated buyers as a result.

There are brands that heal from toxins, scary environmental threats, encourage restoration and retreating to a safe space. These brands are about getting from -1 to 0.

Then there are those that urge users to reach new levels of ability and productivity, to fight against the accepted norm and unlock hidden human potential. These brands are about getting from 0 to +1.

In wellness you are either healing or fighting. And on either side, information drives behavior.

That creates a problem for the masses of new consumers coming into the fold. There is a growing disconnect between early consumers who have been well educated and the wider masses that have a lot of catching up to do.

Because early adopters in this space are so regionally and demographically concentrated, every rising star wellness brand will have to start reaching downwards into the mainstream whether they like it or not. That means connecting a very sophisticated message with a more entry-level one.

The challenge will be figuring out how to connect these two very different groups and the spectrum of users that lies between them.

Perhaps in no other space will it be this critical to thread together different messages with one strong and resonant belief because in wellness, a consumer’s level of education defines the depth of their consumption.

Finance

[Look here if your brand is facing divergent value systems among consumers and institutions, or if old sources of meaning are starting to evaporate.]

Everything about money is emotional.

The vast majority of finance companies, both incumbents and startups, still think it’s about value and wealth. It’s not.

Money is about how we value and respect ourselves as individuals, what we believe we can accomplish, and most importantly, what we believe we deserve.

Someone who treats money like a scarcity is in a very different mental paradigm than someone who treats money like a game.

Today, most of finance is predominantly about a future reward. Savings, 401ks, estate planning, life insurance, portfolio trading… these are all about delayed gratification and value. Delayed gratification and value were also hallmarks of the Baby Boomer generation.

Gen X and millennial value systems, however, have become very present.

Lives, careers, families and identities have become very fluid, and perhaps even more personal and emotional as uncertainty has taken hold around us. We’re starting to see a huge divergence between the fluidity of our emotional value systems and the fixed rigidity of our utilitarian money stories.

The immediate challenge for companies in this space is to bring these financial instruments and services into the present value system of our daily lives. If I don’t know who I’m going to be in 5 years, how can I plan for the next 30?

What does retirement even mean anymore? What is the goal? And if we’re not clear on the goal, how can we write the story around it?

There is a long distance to cover between what money has historically meant, and the meaning it now holds in people’s hearts and minds.

Once you cover that distance, you have to strip it out of the ambiguous future and bring it into the tangible reality of today.

Housing

[Any brand in an old space with a story that refuses to die.]

The American Dream is a very deeply entrenched cultural narrative that connects homeownership with identity.

Even if we understand that the dream has become less and less attainable and perhaps needs to be replaced as a cultural narrative altogether, we still find ourselves lamenting its death. There remains a strong attachment to the idea that our homes mean something important about us as people.

But as with any major economic shift, there is a slew of young companies rushing in to create a new norm.

Startups ranging from those that rethink financing and sales, to those that redefine the mechanics of rentals and co-ownership stand a good chance of replacing the usual American Dream story with something more attuned to reality.

Companies like Divvy, which turn your monthly rent into a down payment on the home you’re living in over time, are accompanied by others like Point (which let’s you sell part of your house), Homeshare, HubHaus, Bungalow (all of which are creating some form of ‘WeWork for housing’), Flyhomes and Opendoor (focused on non-traditional solutions for buying and selling) and many others.

When companies like these create new formats for housing, they also change the way we live in and inhabit our homes.

Our relationship to the home is beginning to significantly change, in no small part because of companies like these. But any time there’s a big shift such this one, we need a strong, new story to effectively frame our experience as consumers. A story that tells us where we are in life, and the meaning that our home is to give us. A story that essentially tells us how to relate to this new living format.

And in this case, the American Dream story simply will not fit.

For brands in this space, there is a huge opportunity to create both a new narrative and a new vocabulary around who a person is through their relationship with the spaces they live in.

As traditional homeownership morphs into something else, consumers will be primed for a new perspective that validates both their homes and their station in life. They will be ready to feel the same pride and sense of accomplishment, but in a different kind of relationship with their living spaces.

We will need brands that can give us that perspective.

This isn’t about a space to live in. This is about what it means to live in these new spaces.

Travel

[If you’re a brand with an audience that’s evolving very rapidly, or in a category that has recently been fragmented.]

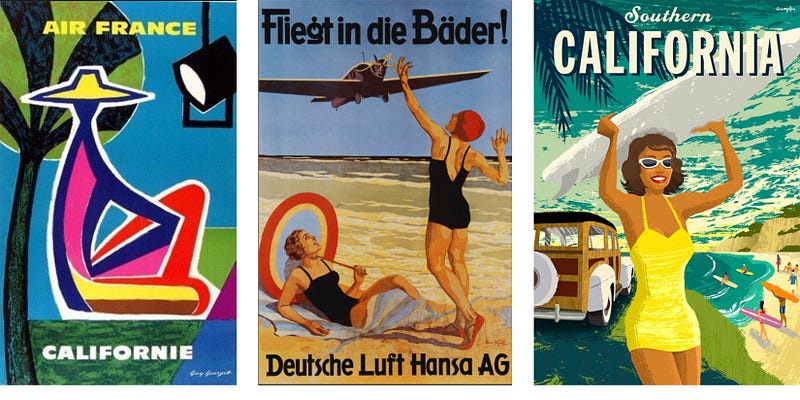

Travel and recreation culture, as it started in the US in the 1950s after soldiers returned home from war, was primarily focused on external values. With newfound time and money, and a newly expanded palate they had cultured overseas, men and their families wholeheartedly bought into this new consumerist category.

But from the beginning, travel and recreation was about an external set of values. It was about leisure time, entertainment, casual fun and of course, middle-class social status.

Today we’ve shifted to a much more internal set of values.

‘Travel and recreation’ has been replaced by ‘travel and experience’. We travel for self-discovery, wellness, personal identity and to find our place in the world. Travel is meant to reveal some deep truth within ourselves.

This is far more of an essential need than a nice-to-have, and with this new function of travel comes a new purpose. Travel is not about holidays, but about daily life.

People have evolved to value travel as a continuous necessity, but brands still treat it like a luxury.

Some people may find ways to actually travel more often, and some will not, but that almost doesn’t matter.

There’s an opportunity to build a brand world that matches this newly emerging consumer belief. Even Airbnb, one of my favorite brands which I’ve written about many times, doesn’t yet go this extra step.

What would the world look like if we talked about travel as a given requirement to everyday life? What if we gently shifted the conversation from travel as a major life event or rite of passage to travel as part of the American experience?

People are already having this conversation with themselves in their heads. They’re ready for a brand story that legitimizes that conversation in the world.

(I talk more about users, their internal dialogues, and how these dialogues shape their identities here.)

Use these challenges as conversation starters in your own company.

I promise that on the other side of each of these problems lies a huge opportunity to not only lead change in your space, but to redefine your goals and future direction as a brand.

Future challenges, in many ways, are just levers for creating a powerful brand.