5 rules for deep storytelling that go beyond the obvious.

I already write a lot about what makes a good story. Equally as important, however, is how you tell it.

If you’ve ever told a good story but failed to get an engaged response, it’s likely because you weren’t opening the world of that story wide enough so that the audience could step inside of it.

The stories we carry with us are carefully wrapped and sealed memories in our minds. We create mental frameworks and language structures around them in order to preserve what’s inside.

But if you want others to experience that story the way you did, you’ll need to pry away some of those layers in order to let them in.

The stories people remember — whether they are brand stories, personal tales or cultural narratives — are the ones that reveal something about the listener, and you can’t do that if you‘re stuck in the perspective of the teller.

Memorable stories also follow some common patterns:

- Repetition: Themes, poetry, recurring feeling… these are the things we are often left with in a good story. If you ever read Love You Forever as a child (or parent), I guarantee the repetition of that book stayed with you for years later into life.

- Surprises: Emotional or otherwise. The surprise character, the surprise twist, the surprise ending… but nothing comes close to the surprise realization. Think of the epiphany you experienced watching The Matrix, Jurassic Park, Philadelphia or Super Size Me for the first time. We all walked into the theater one person, and out another.

- Proof: The proof is in the delivery. If the story tells me something, then the delivery demonstrates its validity. Whether it’s the simplicity, passion, poeticism, authority or conviction of that delivery, it’s how it’s told that matters. Look at any popular TED Talk and you’ll see why.

From these patterns come 5 rules for deep storytelling that we’ll dive into in the next section:

1. Make the first sacrifice.

2. Trade the lesson for the theme.

3. Create pockets of emotional contrast.

4. Don’t give them a chance to ask.

5. Make your claim, then explain it.

As you read, you’ll notice they’re not so much about communicating a story to your audience, but rather creating a shared experience with them.

That shared experience dissolves the separation between you and the listener/ reader/ spectator, so that they may be able to walk inside the same universe you’re revisiting.

If done right, you will cause a small change in others, just as the story created a change within you.

Effective stories leave both you and the audience as different people by the end.

Know where that end point is, and then use these principles to help get them there.

1. Make the first sacrifice.

Storytelling is an exchange where one offers something, and asks the other for their attention in return.

It‘s a clear give and take, just as you might feel in a conversation with a stranger on the subway or a sales clerk — through their intonations and reactions, you will quickly know just how willing they are to exchange with you.

Your first words are the invitation to an intimate trade.

The sooner you can sense the willingness coming (or not coming) from the other side, the sooner you’ll be able to control how the trade plays out.

Conventional wisdom says to open with a personal anecdote in order to create a connection with your audience, but that’s not good advice.

We all have anecdotes, and just because they are personal doesn’t mean the audience will care.

What people do care about, however, is the gesture of sacrifice.

A sacrifice is an intimate piece of yourself that reveals how you view the world.

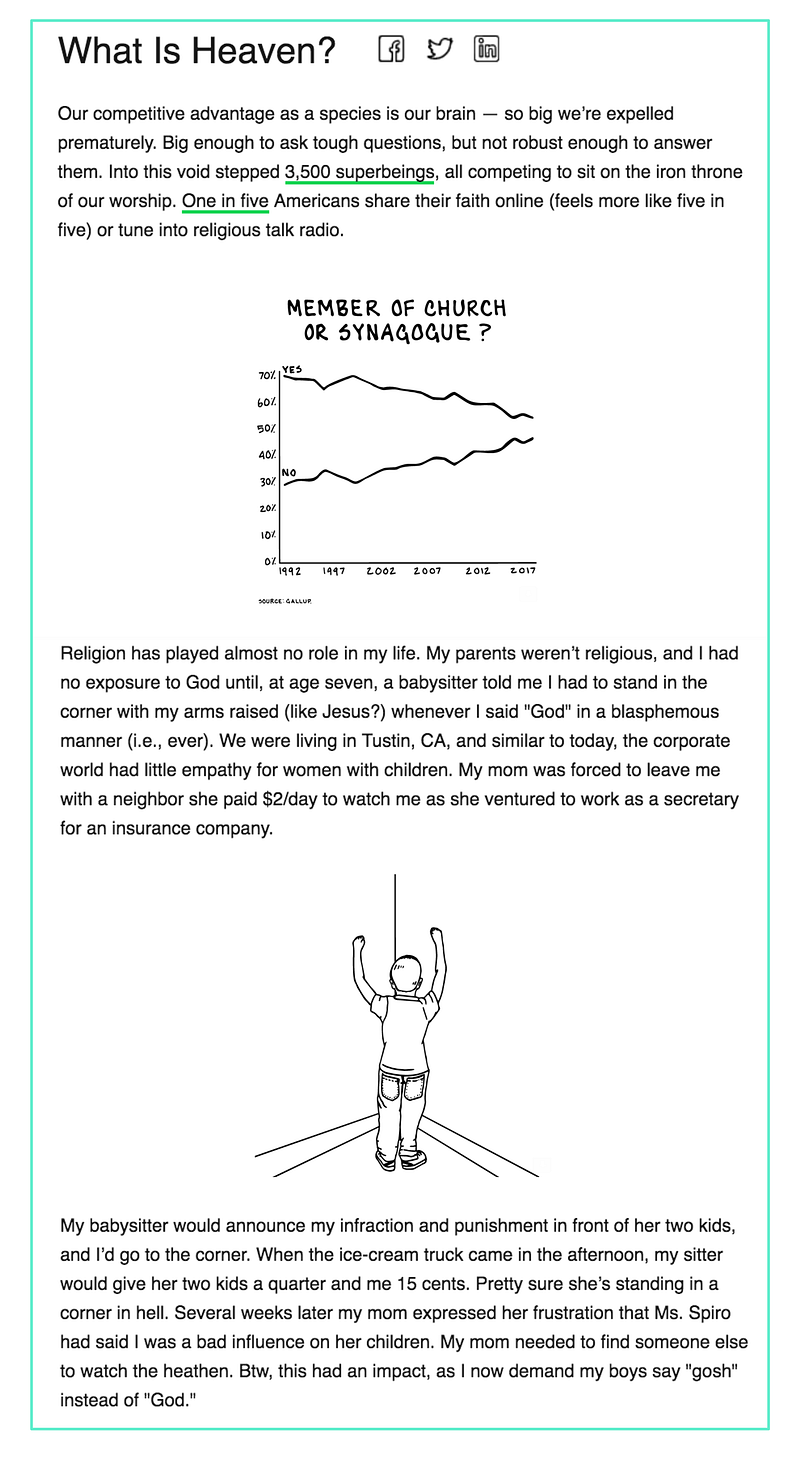

Scott Galloway consistently makes the first sacrifice in his No Mercy/ No Malice blog. Each post masterfully raises the stakes at the top of the exchange.

In the opening for his recent post ‘What Is Heaven?’, he surfaces an unmistakable emotional fingerprint:

This could have easily been a two-dimensional personal anecdote, but instead, he ventured into personal thoughts that expose his view of the world as it was formed. We were actually given something beneath the surface of the story, and that gesture compelled us to move deeper.

In such a moment of vulnerability, you’re offering something of true value — your emotional fingerprint and unique context that signals where the exchange may go.

It is this gesture, not the story or personal anecdote, that communicates your willingness to trade. Your audience can either rise to meet your willingness or shy away from it, but the one thing they cannot do is remain indifferent.

The first sacrifice works because it operates on persuasion.

A recent study by a team of research psychologists in Texas found that when it comes to persuasive communication, framing your relationship with the other party can be enough to sway someone to your will.

A group of dating couples was recruited in order to see if different communication styles yielded different results in relationship negotiation.

The act of framing the relationship worked significantly better than coercion or even rationalization.

…there was a third set of communicators who employed a breathtakingly simple and successful procedure that we term the relationship-raising approach. Before making a request for change from their partner, they merely made mention of their existing relationship.

They might say, “You know, we’ve been together for a while now” or “We’re a couple; we share the same goals.” Then, they’d deliver their appeal: “So, I’d appreciate it if you could find a way to change your stand on this one.” Or, in the most streamlined version of the relationship-raising approach, these individuals simply incorporated the pronouns “we,” “our,” and “us” into their request.

Similarly, storytelling is a negotiation for time and attention.

Framing it in the context of a human relationship can tip the negotiation in your favor… and there is nothing more human than a revealing gesture or intimate offering.

When Galloway says he’s “pretty sure she’s standing in a corner in hell”, he is framing our relationship in a common empathy. Yes, we agree with his worldview, and we want more.

Saying you had a bad early experience with religion is a common refrain with little to offer. Describing how that early experience changed your childhood, your view of your mother in the corporate world, and your relationship with your own children is a true offering.

You can’t just tell the story. You have to give it.

2. Trade the lesson for a theme.

Most people don’t understand how a theme can transform a story, but look no further than some of our favorite cultural narratives and the effect is undeniable.

If we look at recent Pulitzer Prize winning novels and ask ourselves, “what was the point of this story?” it might be hard to immediately say. There may have been no real point or moral to the story to begin with.

If, however, we asked for themes, then the answers jump right out.

- A Visit From the Goon Squad by Jennifer Egan: The unrelenting yet quiet assault of time on our lives

- The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao by Junot Diaz: The inevitability of ill-fated love

- Olive Kitteridge by Elizabeth Strout: The beauty and complexity of even the most mundane lives

Narrative themes come from undeniable human truths that drive every outcome to the same place.

To give your story a theme is to give it an irresistible human depth. Themes reveal themselves over and over again, in different forms, but always constant.

We internalize themes more readily than lessons or morals to the story because instead of learning them, we rediscover them.

Narrative themes are a device we see a lot in television, too.

Have you ever noticed that some of your favorite episodes show different character arcs all revolving around the same thematic message?

In the Parks and Recreations episode End of the World (S4 E6), every character is living out the undeniable life theme of “having to let go of the past in order to move into the future”.

Leslie and Ben finally confront the reality of their breakup as Shauna Malwae-Tweep begins to enter the picture, Tom and Jean-Ralphio shutter their entertainment startup with a massive party where Tom gets closure with an ex, April and Andy finish off Andy’s bucket list as a newly wed couple, and it’s all couched in the story of the Reasonabilists — a cult that is celebrating the end of the world in a Pawnee park.

Everyone is exploring the same theme, but in different ways.

There may be no lesson or point, but the show’s story moves forward in a deeply satisfying way.

The same thing happened in most episodes of The Office, as it does each Sunday night in Westworld.

Themes thread a story together. They create a rich bedrock of feeling that everything else is built upon.

Even when we can’t remember the details of a good story, the theme helps us remember how we felt when we heard it.

3. Create pockets of emotional contrast.

We remember moments of heightened emotion more than other memories.

That’s why stories that compel an emotional response are the ones we tend to remember and repeat. It’s because scientifically speaking, emotion helps encode the story in our brains.

But other than following the conventional advice to communicate with passion and use strings of emotive words, how do we effectively draw out emotion in our audience?

By focusing on the distance between emotional states in the progression of a story.

Emotion is created in the contrasts.

Emotional responses are relative, and you can craft your story in a way that highlights the emotional fluctuations of your narrative as it moves forward.

In his 2014 speech to the graduating class of Maharishi University of Management, Jim Carrey created great distance between emotional highs and lows, one after another, in quick succession.

When he begins to tell his personal story about halfway through the speech, Carrey steadfastly traverses loss, glee, fear, silliness, irreverence, pride and sobering vulnerability without losing a beat.

He deliberately paired together contrasting emotions to create deep pockets of contrast.

Any time the emotion changes in a story, you can create a pocket that invites the audience in.

This goes for brand stories as well.

D2C (Direct to Consumer) brands have to be especially smart in how they position their stories because it’s often the story, not the product, that they’re actually selling.

Biossance, like many upstart beauty brands, has a social cause tied into their business model. But unlike most other brands, they turned that do-good message into an effective emotional spark point:

“A world changed” isn’t about doing good or donating to a cause. It’s about a very tangible epiphany. A new truth.

Brand-led companies like this have a specific point of view, and their stories demonstrate their commitment to it.

Others create emotional contrast through similar ‘aha’ moments — where once life was one way, and now it’s not.

Hims has a very lighthearted story and tone, but their ‘aha’ moment is quite evocative:

“We call bullshit” reverses generations of harmful gendered stereotypes.

You can move the pivot points of your story forward by using ‘aha’ moments, epiphanies and pockets of emotional contrast.

These are great devices for creating the spark that makes a story stick in peoples’ minds.

4. Don’t give them a chance to ask.

One of the most important principles we work into our branding and sales strategies for clients at Concept Bureau is to answer the question before it’s been asked.

Any time you’re telling a story — whether it’s regaling friends at a party, pitching a client, winning team buy-in or soft selling an idea — it’s imperative to anticipate the needs of your audience so that no questions arise.

If you give your listener a chance to ask, “wait, how did that happen?” or “hold on, didn’t you feel scared?”, you’ve lost control of your narrative.

And chances are you won’t even be able to answer the questions in the first place. Most people ask in their heads, but never out loud. Then they zone out and you have no chance at owning their interest again.

I listened to Howard Stern during a year of free Sirius XM that came with my new car, and despite my ambivalent feelings on the nature of his content, I couldn’t deny just how masterful an interviewer he was.

There was one interview so good, I sat in my parked car for 20 minutes after my bootcamp class had started, and nearly missed my session altogether:

Gossipy indulgence aside… why was it so good?

Because Howard Stern pushed Franco to answer the burning questions in our minds when he sensed Franco wasn’t giving them to us.

Howard Stern, not Franco, made the story emerge.

He gently guided the conversion so that no question lingered in our minds for more than a moment.

We’ve all been on the other side of that conversation where someone may be talking in detail, but fails to anticipate the things we are curious about. That makes for a frustrating and un-memorable experience.

You can certainly build tension with the plot of your story, but don’t create tension with the details.

Memorable stories anticipate the things we will be curious about.

There’s an old political adage that says “If you’re explaining, you’re losing.” That’s basically all you need to know on this point.

If there is a lingering question, you’ve created distance between you and your listener.

Even if your story is written or presented asynchronously with your audience, imagine your listeners are in the room with you. Let them interrupt you and guide how to move forward.

When there is nothing to ask, people can give themselves fully to the narrative.

5. Make your claim, then explain it.

Most people do this in the reverse order.

We often explain and explain until we finally arrive at our point.

Confident people make their bold point up front and then follow with an explanation. It’s not only more satisfying for the listener, it’s also an effective way to convey authority.

Making your claim first is like putting your flag on a map.

It’s like saying, ‘This is where I am taking you. Now let me show you how we will get there.’ If you reverse that sentiment, it loses all of its power.

Warby Parker does exactly this with their About page (red underline added):

The story first plots each point with conviction, and then explains how they arrived at that point.

Although it may seem a bit stilted and counterintuitive in practice, writing a story this way creates an authoritative voice that much easier to trust and follow.

Compare that to the story of the Australian eyewear label Pared:

This is just as true a story as Warby Parker’s, but notice how different this chronological telling is when there is no mapping of strong points for the audience to tether themselves to.

Not only is there no structure, but there is no memorable anchor to internalize. If there are meaningful points, they are buried in a stream of consciousness.

To tell a strong story, lay out your claims at the top of each arc.

Many of the keys to being a good storyteller are the same things that make you a good communicator.

Unforgettable stories are the ones that make people realize something about themselves.

Make them take a side.

Force them to reconcile something in their heads.

Change their worldview (no matter how slightly).

Stepping outside of yourself, making the memory come alive and creating a shared experience with your audience are, more simply put, just ways to lower the barrier between you and another person.

If you have a great story to share, make sure you’re sharing it in a way people can truly experience.