Brand strategy, at its core, is about predicting the future and then making that future a reality.

The outsized benefits of brand live 3, 5, sometimes even 10 years ahead. Brands that pull that future into the present day change users’ consideration sets and bend the will of the market toward their doorstep.

Strategists are futurists. There is no strategy without a prediction.

If you get those predictions right, you will get a brand strategy that amplifies the business strategy rather than trailing it.

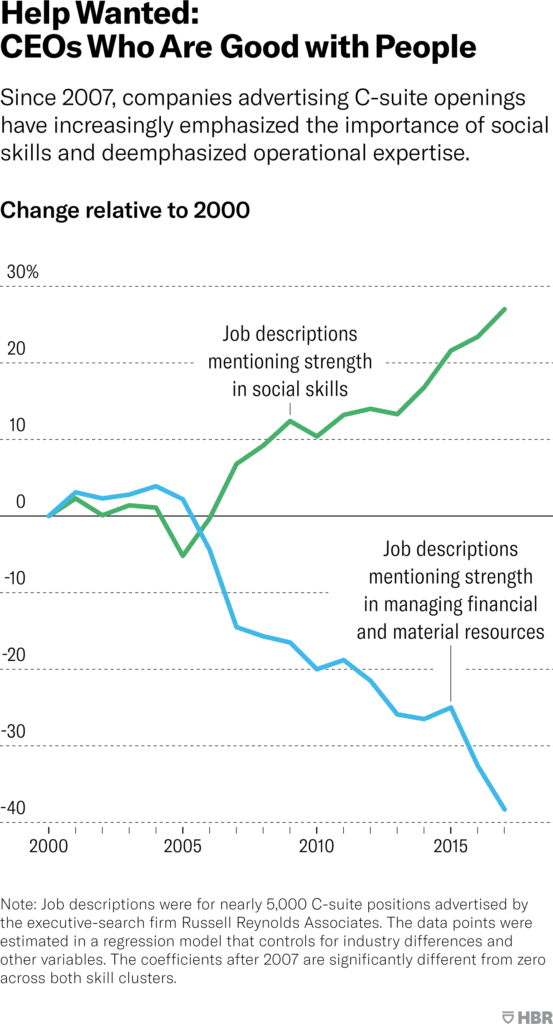

There is one future signal that has an immediate impact on branding for nearly every company in the next few years and it can be found in a simple, unassuming chart about C-level job postings that was published in HBR this month.

In the study, researchers found a rapidly growing appetite for CEOs with strong social skills coupled with an equally declining appetite for operational expertise. In other words, companies want leaders who know how to leverage and navigate culture more than they want leaders who know how to direct financial resources and technical expertise — and the inverse relationship between these two needs has only gotten more dramatic in the last 7 years.

It makes sense that as companies have become more complex they need leadership with higher levels of interpersonal fluency, but something else is happening behind the executive curtain.

The trifecta of consumer brand, the CEO’s personal brand and the company’s employer brand are all becoming the same thing.

Company boards are increasingly searching for ‘blue unicorns’ — leaders with powerful social presence who, as Peter Aceto, former CEO of Tangerine once said, “would rather engage in a Twitter conversation with a single customer than see our company attempt to attract the attention of millions in a coveted Superbowl commercial.”

Blue unicorn CEOs are no longer figureheads for the company brand, but rather direct expressions of the brand itself.

Our perceptions of what makes a great leader have changed significantly in the last decade, due in part to lockdowns, unprecedented scandals of all kinds, and never-before-seen market dynamics. Today, we expect leaders to be highly self-aware, open and at times even vulnerable.

In fact, there is growing evidence that the number one predictor of someone’s success in today’s business climate isn’t IQ (intelligence quotient) or EQ (emotional quotient), but something called CQ: the quotient that measures “the capability to function effectively in a variety of cultural contexts.”

CEOs must first and foremost be stewards and navigators of culture. But there is perhaps an even larger brand benefit here.

Celebrity CEOs like Jay-Z, Martha Stewart, Steve Jobs, Elon Musk and Adam Neuman have created brands that make them impervious to angry boards and poor P&Ls, but also trained the public to demand a certain kind of enigma from its corporate leaders.

Enigma, charisma, whatever it is, we now expect a certain awe-inspiring magnetism from our CEOs, and this is increasingly the yardstick for measuring good leadership, instead of more historically important markers like strategic thinking and industry expertise.

Meanwhile, the public’s growing appetite for business news over the past few years has incented media to not only cover more business, but reduce its happenings into easy-to-follow storylines, which are bedazzled with drama, gossip and mystery.

The CEO has become a cultural bellwether.

And you can’t talk about culture without talking about the third piece of the branding trifecta: employer branding. Knowing how to build, navigate and bridge cultures is the biggest thing we see in employer branding today.

There is the obvious benefit of attracting high-level talent, but as my colleague Zach Lamb has pointed out, markets and consumers are paying attention to employer branding practices and cultures.

In our own research at Concept Bureau we’ve seen that in B2B sales a surprising number of clients will first vet a services partner by their Glassdoor reviews, believing that if that partner doesn’t treat their employees well they won’t treat their customers well, either.

As work memes take over our feeds and what happens inside a company continues to make the news, companies can’t afford to have an employer brand that is not completely synonymous with their overall brand.

In the near future we’ll be seeing Brand Singularity, where personal brand is company brand is employer brand, and the product is the story that emerges in the overlap of all three of these things.

Today’s typical brand addresses the trifecta with three different answers. Netflix’s consumer brand is closely tied to their content. CEO Reed Hasting’s personal brand is visionary at times, while lacking in more recent times. And their employer brand vacillates between ruthless and confused.

On the other hand, we have Hello Sunshine, Reese Witherspoon’s female-focused media company that has produced hits like Big Little Lies and Little Fires Everywhere in the eight years since it launched. They have not reached brand singularity yet, but already they are making inroads toward it and seeing the benefit.

Their content portfolio is thin, but there is a singular, synonymous brand between Witherspoon’s persona and the consumer brand. She is Hello Sunshine, and Hello Sunshine is her. It’s an overlap that is so powerful that Witherspoon just sold the company for over $900M.

Hello Sunshine is no Netflix when it comes to market cap, but $900M for a fledgling studio in a contracting market is by all measures outsized when compared to the giants in the room.

In the next 5 years, we will see companies reaching Brand Singularity and reaping the early rewards of market share, fandom and talent retention. They will be the companies that have done the hard work of creating a unified brand front — not synchronicity like we have seen with branding in the past, but instead synonymity.

Right now we see only parts of the equation being written. Many companies master personal brand + consumer brand, such as Hello Sunshine, but also the ventures of the Kardashian-Jenner clan and MrBeast. Even with only half of the Brand Singularity equation figured out, these names are making big profits.

As David Friedberg recently said, the influence of these brands is outsized and defensible. They prove that when the CEO is a direct expression of the brand and vice versa, their value takes on exponential proportions.

On the other side of the equation we see inroads being made with the overlap between employer brand and consumer brand.

Amazon may not be one of the most positive employer brands in their warehouses, but it is one of the most effective employer brands in the executive realm. If you pay attention to all of the messages in their press, good and bad, you will get a clear message about their operational excellence.

It’s no accident that stories about the empty chair in the meeting, the two pizza rule and three good decisions a day not only made their way into public consciousness, they served as signals of what the overall Amazon brand was about. Prospective talent, especially elite leaders, understand that even with rumored cutthroat practices, they would not be hindered by underperforming teams — a common concern among the many high quality leaders I have personally interviewed over the years, and a fact Amazon is banking on.

Amazon’s employer brand and internal culture is in reality a marketing vehicle for both attracting talent and buttressing the consumer brand. As Prime members, we read those stories with disdain, but somewhere in the back of our minds we know that’s likely why our packages miraculously arrive within 24 hours.

I recently wrote that the employer brands that consistently attract elite talent are the ones that lean on vision, not mission. Vision creates the kind of high-risk, high-reward messaging that great brands are built on. Many companies fall to their missions because they help keep the status quo internally, but it’s the vision that keeps a company’s workforce adaptable and responsible to the larger brand.

It’s been my experience that Brand Singularity, even if only partial, creates vast operational efficiencies.

Teams naturally move away from siloed practices that hold the company back as a whole. People in every single department find it easy to act as a brand owner in their own capacity (a CMO’s dream). Values, missions and visions stop being weaponized and start getting used properly. Positive internal cultures build faster and the circle around “who we are and what we do” becomes tighter.

Brand Singularity is just as much an operating principle as it is a branding one.

Having a single identity that captivates and motivates all audiences — customers, employees, prospective talent, board members and investors alike — is the inevitable outcome of a dynamic world where no one group is siloed and no one side of the business works in a vacuum.

Brand Singularity is incredibly hard to reach but will be a major competitive advantage for those that achieve it.

We’ll be seeing more and more brands moving toward this new state over the next 5 years, and it will require a conviction and dedication to brand that we perhaps haven’t seen much of yet. But once it starts popping up across the landscape, it will be the defining factor between brands that attract value from the market and those that chase it.