On signaling behavior, moving the defaults and taking big swings

For a few weeks during the Coronavirus’ spread across the United States, Americans all spoke the same language.

Phrases like “flatten the curve” and “social distancing” entered our lexicon. Many have documented our new set of social norms, from stepping away from strangers on the street (once awkward, now thoughtful) to wearing a mask in public (once suspicious, now a sign of good citizenship).

But then these shared standards began taking on political connotations.

As government officials split over next steps in the battle against the virus, Americans fell back into factions, now perhaps easier to distinguish than ever. Those who stepped away from strangers on the street and those who didn’t; those who wore masks and those who wouldn’t.

Stores became battlegrounds for this changing, charged environment. Customers at Costco and Gelson’s filmed seething cell phone videos in response to mandatory mask policies, which quickly went viral. For some viewers, these moments became cause to support the brands, while others pledged to cancel their memberships.

By simply following government orders or recommendations, these companies made an inadvertent political statement, entering into a heated cultural conversation.

And yet, this is just another proof point that our societal frameworks are changing.

When societal frameworks shift, your brand’s actions are perceived through a different lens.

As Scott Galloway heralded in 2018 after Nike made Colin Kaepernick the face of their 30-year anniversary “Just Do It” ad campaign, our leadership has politicized sports — the last “oasis” of politics-free discourse — and has since then upped the ante in making everyday acts partisan in nature.

This is likely a reality that we can never revert away from again.

In moments of crisis, brands attempting to reestablish their commitment to consumers face a particular challenge, one that can easily go awry if you don’t pay attention to the societal framework shaping our choices.

There is a subtext to every move, an implicit bias or belief to every action. Brand perceptions don’t just come from words or actions — they come from reading between the lines.

That means you can’t make brand choices in a bubble. You need to consider the culture and the belief systems that those choices live within.

So, let’s look at some of the implicit forces at play.

The power of signaling behavior

As Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti began increasing the number of Coronavirus-related regulations in the city, he often returned to the idea of “self-enforcement.”

Acknowledging the logistical nightmare of trying to impose social distancing in all of the sprawling city’s public spaces, he instead maintained that individuals would personally analyze the risk and choose to heed his advice. Once enough people did that, the rest would likely follow suit due to perceived or voiced peer pressure, not wanting to stand out from the crowd.

In other words, adhering to social distancing became what sociologists call “signaling behavior.”

I spoke with Rory Sutherland about this concept for our brand strategy + culture podcast, Unseen Unknown. Sutherland is the Vice Chairman of Ogilvy, prolific thinker, and author of acclaimed brand strategy book, Alchemy.

To explain signaling behavior, Sutherland pointed to the practice of taking business trips to visit clients. Oftentimes, an in-person meeting is not the most conducive to productivity, particularly when you factor in the time and cost lost in travel.

Yet, the business trip has remained a standby not because of its efficacy, but because the gesture signals a high level of commitment. It proves to clients that they are valued, important enough for you to make personal sacrifices on their behalf.

For many brands, signaling behavior has become a key strategy to connecting with consumers amidst the Coronavirus.

With limited access to their self-isolating audiences, companies including Coca-Cola, Walmart, and Dove all released what New York Times critic-at-large Amanda Hess has dubbed the “pandemic ad:” spots focusing on the valor of front-line workers, with little to no actual acknowledgment of any products or services from the brand.

Instead, the ads signify that, by buying from these brands, you’re supporting a company that understands your concerns. That shares your admiration for everyday heroes. A company that gets it.

Just like Sutherland’s example of an employee taking a business trip to convey devotion to a client, these brands are spending their advertising budget to prove that they are there for you, a reliable constant during “these unprecedented times.”

Hess points to Facebook as one of the most persistent purveyors of pandemic ads. The social media giant has seen a spike in users this spring, up 10% from the same time last year. The brand has seized onto this surge, rolling out quarantine-friendly features for users that range from a new video calling option to a “feel-good” reaction emoji.

After years of declining users and scandals that made the act of quitting Facebook itself a popular signaling behavior, these actions have helped the brand once again become synonymous with connection and innovation — and not just in their approach to consumers.

Choice isn’t always enough. Sometimes, you have to change the default.

Facebook most recently made headlines for CEO Mark Zuckerberg’s announcement of the company’s new remote-friendly employee policy, which he claims will make it the “most forward-leaning company on remote work at our scale.” Despite his trailblazing rhetoric, Facebook is not the first to take this step, with Twitter quite notably offering employees the right to work from home “forever.”

Across the country, an estimated 34% of US workers are remote due to the pandemic, with a sizable percentage likely to never return back to their previous in-office schedule. With that perspective, the policy change these Silicon Valley giants touted as pioneering can seem more like an inevitability of this moment.

But what is revolutionary about their announcements is the framing of work from home as the new standard.

By making it not an option, but a key factor in establishing themselves as a “forward-leaning company,” they have effectively changed the perception of remote work as a default rather than an outlier.

Working from home is no longer for B-players and non-core employees. It is the new standard, and now those people who have to go to the office may be the ones carrying a stigma.

This is another concept I discussed with Sutherland. Acknowledging that we are, as he notes, a “copying species,” he explains how simply giving employees a choice to work differently will typically fail to create any real shift in behavior. For most, the threat of standing out remains too high — even if employers say work hours are flexible, few will chance being the only person to eschew the culturally accepted 9–5 workday.

Think about the paradox of unlimited vacation. Employees at companies that offer what seems to be this fantastic perk have repeatedly proven to take less time off for fear of surpassing the norm.

That’s why, to truly encourage new behavior, Sutherland recommends changing the default rather than providing options. He advocates the adoption of what he calls “Libertarian legislation,” or giving people the “right to do things differently” through permission-granting policies.

Don’t just give people choices. Give them new defaults and permissions that can actually change behaviors.

[You can listen to Sutherland talk more about his theory on “Libertarian legislation” on our podcast here.]

For brands, changing the default isn’t limited to implementing structural changes. It can also mean redefining the culture around your products.

Billie, a toiletries company best known for shaving kits, perhaps confusingly calls itself a “hair-positive” brand. What seems at first to be a contradiction of its perceived goal — to sell razors — proved to be exactly what set it apart in the crowded industry.

By encouraging people to see body hair as the norm, they’ve created a space where purchasing personal care products no longer feels like a response to societal pressure, but instead, an opportunity to support a brand aligned with progressive values.

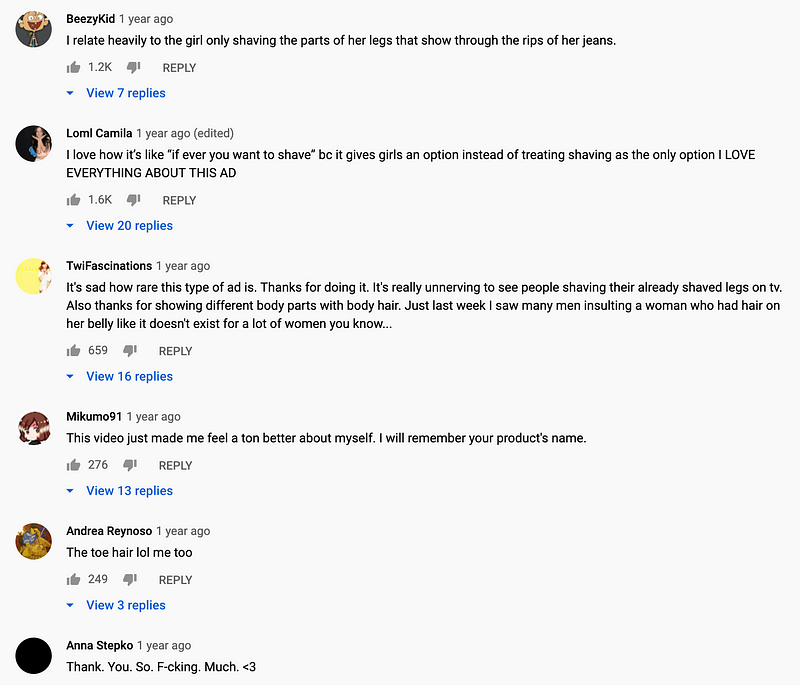

Their flagship video, a celebration of body hair and the choice to shave or not, was noteworthy in its message. But even more noteworthy were the thousands of comments, most of them overwhelmingly appreciative.

The messaging has seemingly paid off, with the company reportedly seeing a 268% increase in sales volume between December 2018 and December 2019.

By changing the norms, you change the reasons for using your brand.

Recently, Billie launched an additional set of personal care products, accompanied soon after by a social media call encouraging people to stop apologizing for “looking like ourselves” while working from home.

Once again, the brand received widespread praise for their candor in encouraging body positivity.

For Billie, a counterintuitive marketing campaign wasn’t new territory — but for Uber, it was.

Don’t be afraid of trying something new in response to a crisis.

In April, the ridesharing app put out an ad thanking users for “not riding with Uber” due to Coronavirus concerns. It was an unusual move, but one that paid off by keeping the brand top of mind despite its lack of use to customers at the moment.

Crises create instability, which can make it seem like a daunting time to take risks like Uber did. As Sutherland sees it, though, times of uncertainty actually give you the latitude to experiment.

While he believes we are typically predisposed to “incremental” improvements due to fear or failure, he points to the proverb that “necessity is the mother of invention” to illustrate how we are open to bolder ideas during difficult times.

- Just a few months ago, Democratic presidential candidate Andrew Yang was largely dismissed for promoting universal basic income; today, multiple countries, including the US, have implemented schemes along those lines.

- Brands like Ford, GE, and 3M quickly pivoted to meet the manufacturing needs for respirators and ventilators to fight coronavirus.

- Fashion designers went from drawing gowns to making masks.

- Beauty brands all around began manufacturing and selling hand sanitizer — and it will likely be the new mainstay for a beauty brand’s product mix going forward, just as with face wash and serums before it

Changes don’t even have to be particularly radical to be impactful. Consider the King Arthur Flour brand.

After the company saw its sales increasing by 600% overnight in response to the frenzy of quarantine bread baking, the 200-plus year old brand took some out-of-character steps.

It shifted both its production and transportation models, doubled its social media and call-in hotline teams, and even began producing two new shows on YouTube.

With these moves, it not only met the needs of its customers, but also innovated to better serve them across platforms and in new ways.

Sometimes the biggest brand moves are simple moves. You don’t need to be radical in order to be impactful.

For brands, this can be a key time to take a look at the broader societal playing field and make forward-thinking changes with this bigger picture in mind.

Keep in mind that there are cultural shifts, but your brand may exist in a smaller subculture that has its own rules, too.

How can your brand contribute to the cultural/ subcultural conversation? What needs are you uniquely positioned to address?

Think about your users’ shifting attitudes about themselves, their communities and the universes they live in. We are constantly renegotiating these relationships and refining our world views.

Prove to your customers that you’re paying attention. Instead of falling victim to the implicit forces at play, use them to inform your brand’s position.