3 Ways To Redefine Your Business Through Branding

Your brand is a series of consistent decisions that bolster your positioning and demonstrate what you stand for. You should be able to take any business decision — HR, sales, communications, operations, PR, product, UX/ UI, or otherwise — filter it through your brand identity, and arrive at an on-brand answer that you can act on.

That’s not an exaggeration. The best brands do it every day, from high-level strategic decisions to day-to-day tactical actions.

On a strategic level, we see numerous examples of companies that based their business choices on their brand strategy:

- WeWork moved into living spaces and childcare because of their belief in utopian communities. Rather than following their capabilities into new co-working formats, they followed their brand belief into new centers of citizenry.

- Apple saves all of their PR announcements for a few highly publicized events a year because they believe their brand is about an elite experience, not a continuous rollout of features.

- Four Sigmatic, a beverage company selling popular mushroom coffees, recently launched a new category of products in the beauty space because their brand isn’t about health drinks, it’s about optimizing the body.

- Airbnb released a hosted city experiences product as a vehicle for their ‘belong anywhere’ brand belief. The brand was the basis for the product.

View this post on Instagram

On a tactical level, we see companies make small (but meaningful), everyday choices that bring their brand strategies to life as well:

- Zappos trains its customer service team to have longer, more meaningful and textured conversations with users, often providing backstory and personal feedback on the items. It’s a costly tactical choice based on their strategic commitment to being the anti-Amazon.

- Red Bull often dropped hundreds of empty cans outside of nightclub dumpsters in the early hours of the morning so that clubgoers believed the drink was for hardcore partiers. Their strategy to reach an untapped influencer market led to a clever WOM guerrilla marketing tactic.

- Harry’s Razors creates emotional video content around men’s issues to push forward their belief in challenging toxic representations of masculinity. The content is dictated by the brand, not SEO.

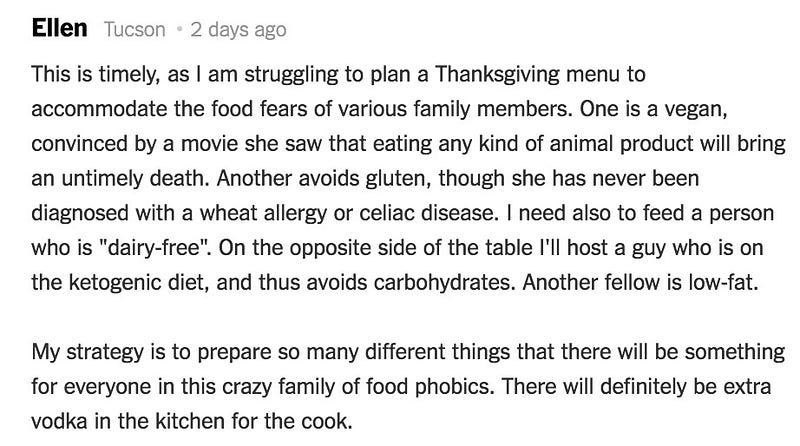

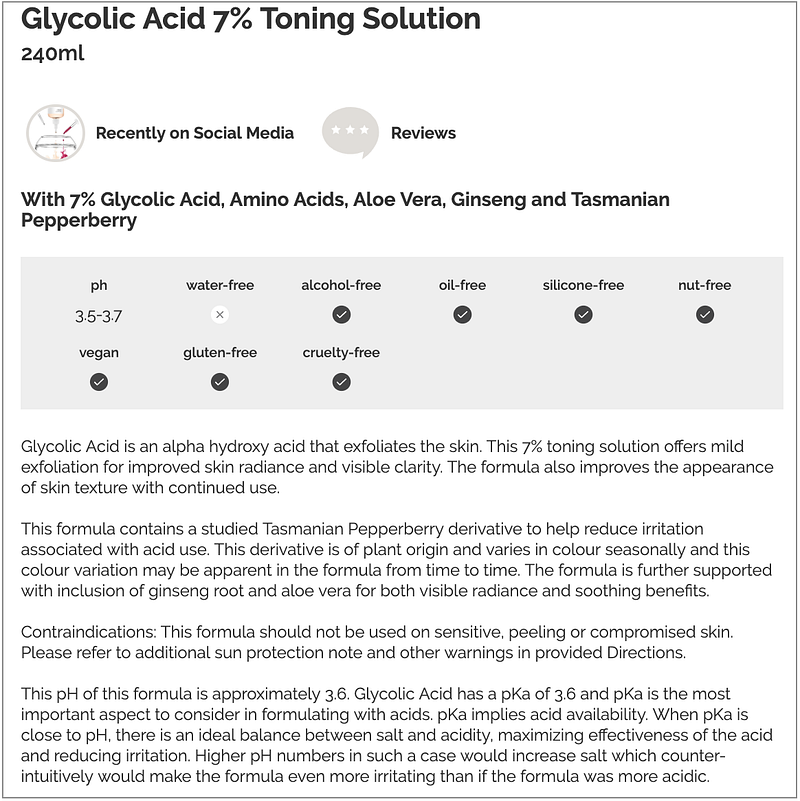

- The Ordinary deliberately packages their beauty products in identical, hard to understand packaging labels so that users spend hours figuring out the routines and combinations are right for them. This clever packaging tactic has created a huge online community of beauty fanatics that share advice and ingredient recommendations — a testament to The Ordinary’s strategy to turn everyday users into discerning beauty experts.

Brand strategy is a daily choice in every department, in every activity.

That’s because brands exist between the lines. Consumers understand a brand by the decisions it makes.

If your brand isn’t informing actual business decisions — not just marketing or design — then you’re not really building a brand.

It follows, then, that the way you define the word ‘brand’ is critical your company’s trajectory.

Do you subscribe to any of these definitions?:

- The sum total of all your touch points with the customer, or, as Seth Godin put it in 2009, a brand is “the set of expectations, memories, stories and relationships that, taken together, account for a consumer’s decision to choose one product or service over another.”

- A brand is a feeling, which is often synonymous with an aspirational aesthetic or thought leadership

- A brand is a unique voice or personality. Taken to the extreme, brands are one of the 12 brand archetypes like The Hero or The Outlaw.

- Brands are an intangible asset — the line of goodwill on an organization’s balance sheet that captures the extra premium a customer is willing to pay above and beyond the actual product

Most people use at least one of these definitions. The problem with all of them, however, is that they describe a set of static characteristics.

The new definition of the word ‘brand’ captures, instead, a measurable change.

Whatever your story is — and by story, I mean the narrative that ties your product, voice, UX, team, history, roadmap, everything together — it needs to create a new sense of meaning that didn’t exist before your brand made it a reality.

Brands are not fixed characteristics. They are dynamic movements that make something matter.

A brand is the creation of meaning where there was none before.

That’s vitally important because it changes the way a business functions.

So how do we take this new definition and bring it home in a way that is actionable within a company?

As with all things branding, there is more than one way to arrive at the right answer. Here, I offer three ways to slice the challenge and move forward.

These are only a few, certainly not all, ways to articulate the act of ‘creating meaning where there was none before’.

You need to be deliberate about which definition you choose (or create) for your own brand because how you define it will ultimately dictate your strategy — and your strategy will dictate whether you win or lose in the market.

1. Brand Is A Gateway

LEGO has used their brand to create meaning for parents where there was none before.

Every time you catch a hidden hidden joke just for adults in their movies, come across LEGO FORMA kits for stressed out professionals or see a print ad meant to make a 30-something chuckle, that is the brand winking at you and whispering, ‘you should play at every age.’

LEGO’s brand creates new significance for parents who believe they were supposed to stop playing a long time ago. Non-children are given opportunities to engage, and they’re hidden right in plain sight… a sort of peekaboo game in and of itself.

While Sesame Street and Disney also nod to parents in a similar way, LEGO is different because it opens up a space for change that didn’t exist before — a space where parents have permission to be children again. There is meaning in that transformation.

When a brand acts as a gateway, it promises a change in the user.

When we come to understand that we should ‘play at every age’, we realize something about ourselves, and we understand that to go through the gateway is to emerge someone different.

Brands like LEGO are constantly working to show adult users what their experience can be like on the other side. There is a clear vision of before and after that forces a reaction.

To be a brand like this is to create meaning in the act of crossing the threshold.

It informs their decisions to release adult products, inject tongue-in-cheek double meaning into their content and move into media. The business sits on top of the brand, not the other way around, and that makes the meaning they are creating that much more impactful.

2. Brand Is A Remix

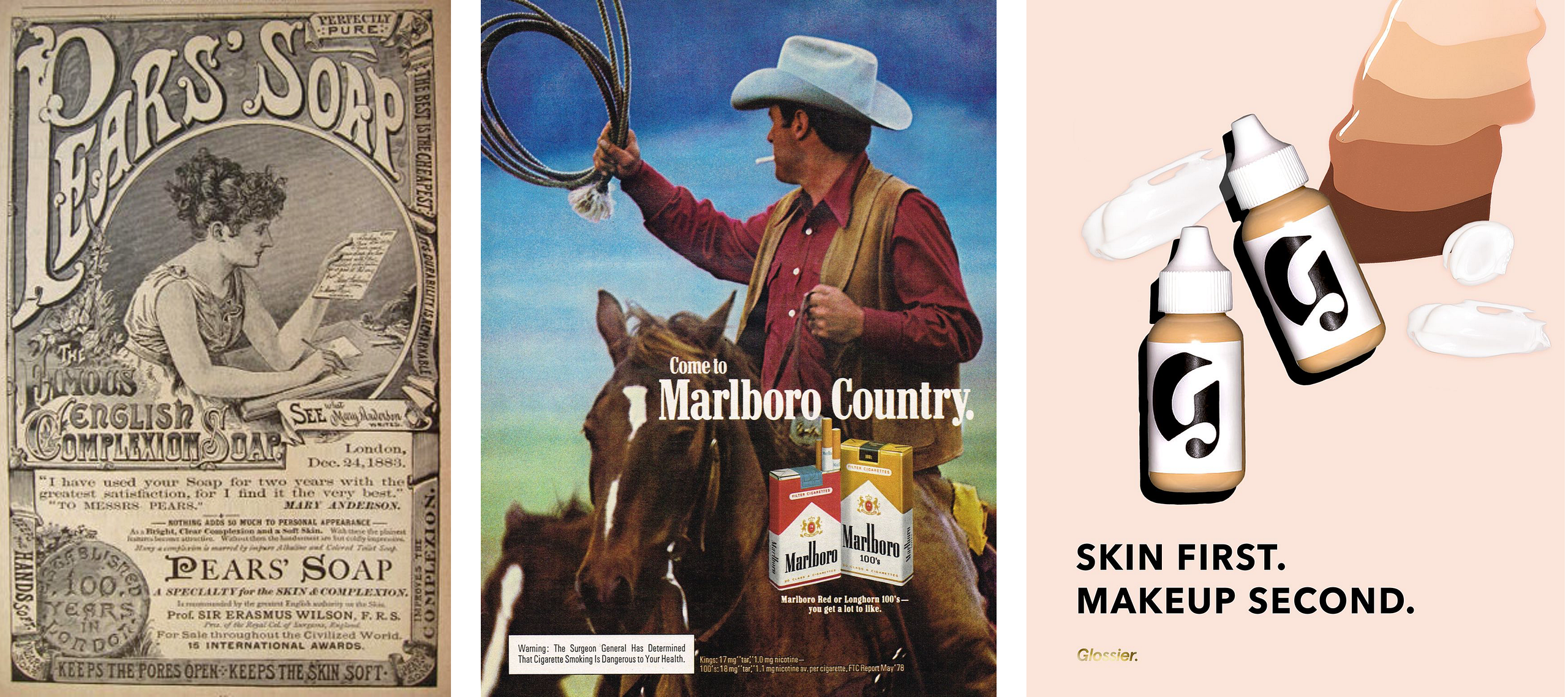

Greek philosopher Parmenides of Elea said Ex nihilo nihil fit, or rather, nothing comes from nothing.

Every new material, creation or concept is borne of others that already exist. The deeper you get into branding the more true this seems. It echoes another common refrain often heard in the marketing world that ‘everything old is new again’. Every new idea is a remix of ideas that came before it.

The thing about remixes, though, is that even though they may not come from new origins, they do take us to new places.

Vitamix, remarkably, created a cult around the humble kitchen blender, and they did it while charging people upwards of $500 at a time.

It’s easy to see the stoic machines as wellness status symbols today, but you have to remember that in 2013 consumers had no idea that the words “luxury” and “blender” could work together so well, nor did they think they needed a 2-horsepower engine to make their morning smoothies.

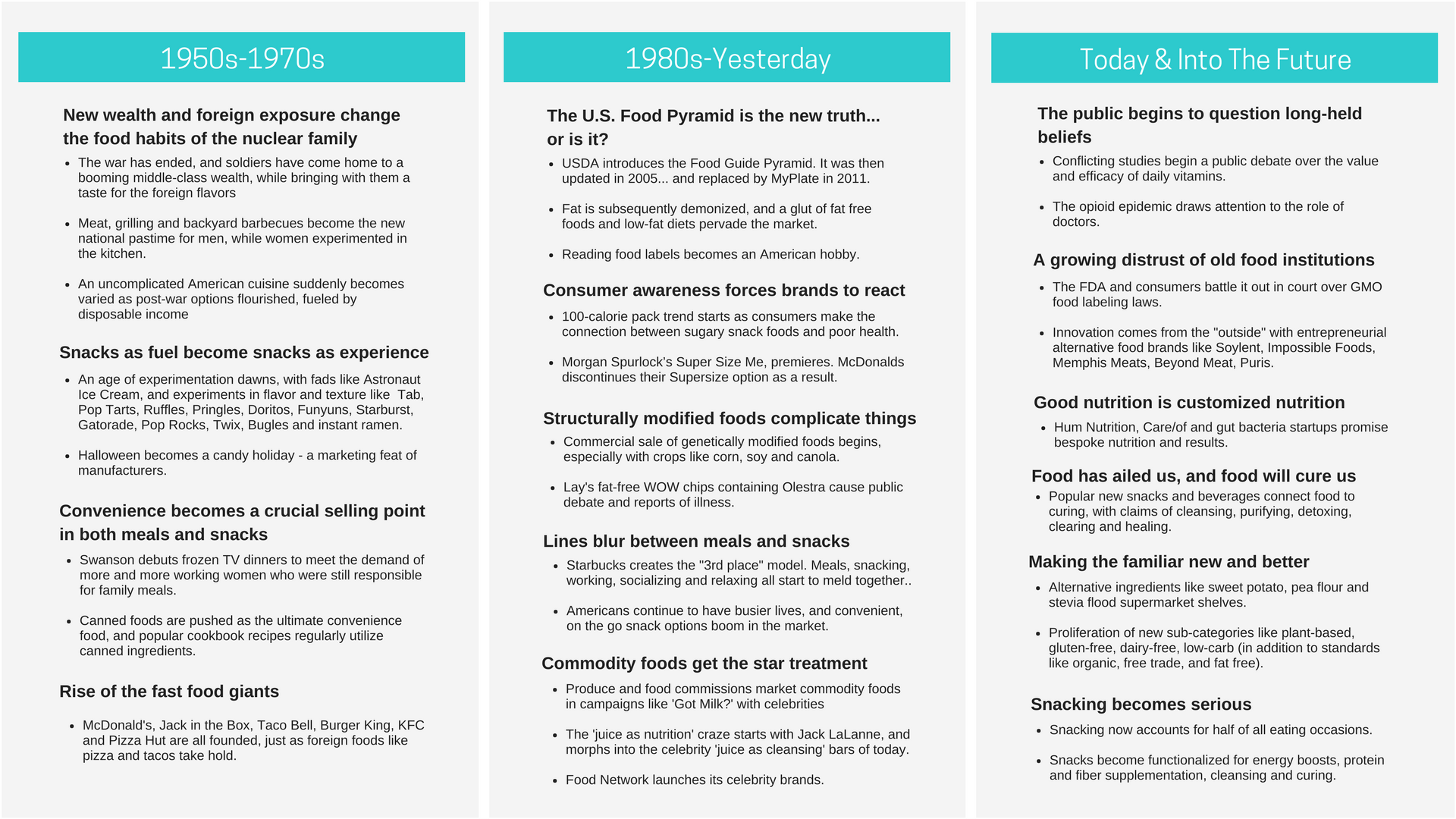

The Vitamix brand wasn’t just about healthy eating. It was a very deliberate remix of extreme power wrapped up in notions of self-care that could demand a premium price. It combined the story of strength with gentler beliefs that were starting to emerge around wellness, to create an audience that looked more like a trendy club than a demographic — skewing toward affluent, health conscious men despite the fact that the company came from pretty granola beginnings in the 1930s.

Vitamix created meaning around the everyday luxury of smoothie making that didn’t exist in the mainstream before. Certainly not in the kitchen. There was a new significance to the appliance that only occurred when two different narratives were combined.

The company radically grew sales through Costco, primarily via energetic demonstrations over a loudspeaker and free samples of whole fruit margaritas, green soups and nut butters circulating in the crowd. It was a spectacle that combined their power-driven angle with a luxury price point that only made sense in a store that promised middle class luxuries in a highly curated format for older millennials.

And you may not realize it, but you see Vitamixes every day at your favorite Starbucks. Sure they’re a corporate client, but Starbucks is also a strategic bit of product placement in the movie that is millennial life. That same kind of product placement has sold out Oatly oat milk in the US.

Brand remixes have occurred in other areas of food, too, specifically in the celebrity chef space.

Why was Gordon Ramsey such a sellable brand?

Because he operated from the belief that you can be a crass and vulgar person but still make highly refined food. You can literally feel the tension in that combination, and it forces you to love him or hate him.

Why was Rachael Ray able to create multi-billion (not million) dollar businesses on the back of her name?

Because she dared to not only celebrate low-brow cooking, but venerate it. She cooked 30 minute meals out of canned foods and pre-cut produce, and was proud of it.

They were both remixes that made people see something they couldn’t see before. They created new meaning where there was none.

3. Brand Is A Key

I’ve talked about brands as master keys before. A good brand strategy will solve 5 problems with 5 solutions, but a great strategy will solve 5 problems with 1 solution.

When a brand is a key, it creates new meaning because it lets people enjoy contradictions without having to account for them.

In other words, it lets people have their cake and eat, it too.

Costco uses a master key to solve a few brand problems at once. They’re a physical retailer living in a world where online marketplaces like Amazon have taken over in both selection and last mile delivery, and yet Costco keeps growing.

Once lumped in with Walmart, Sam’s Club and Target, Costco has somehow managed to develop a brand image that resists discounter stereotypes, compels people to make long and inconvenient pilgrimages to it’s locations, and all without spending money on a PR or traditional marketing.

They solve all of these problems with one choice — to position their brand as a pillar of honesty — their master key as a brand.

Retired CEO Jim Sinegal once said, “We try to create an image of a warehouse type of an environment […] I once joked it costs a lot of money to make these places look cheap. But we spend a lot of time and energy in trying to create that image.”

Costco spends significant money to create a raw, unfiltered, un-marketed experience. When you shop there, you get the distinct feeling that you have behind-the-scenes access without the selling layer. It’s been engineered to feel like an honest experience.

There are no point of sale ads, no finished floors or ceilings, and product is sold on the same crates it’s shipped on.

Even though they force consumers to buy huge quantities, they make no secret of the fact they they markup prices by no more than 15%. They choose to keep very little mystery behind their business practices.

Every year around the holidays you will hear provocative stories about Amazon’s poor worker conditions and failure to treat temporary workers with basic respect.

But every year, you will also hear stories about Costco’s incredible work policies, high pay hovering around $20 per hour for a floor worker, and the fact they remain closed on major holiday moneymakers like Christmas, Thanksgiving and Easter because they believe in respecting their employees.

When a brand is a key, it opens up the possibility of two worlds at once. You can be a deep discounter and yet at the same time be premium. You can follow stodgy business models but be perceived as nimble. You can be cheap, and yet generous. You can be a complete inconvenience and still be a pleasure to use.

When contradictions occupy the same space, they create a new meaning around what is possible.

When a brand creates new meaning, it creates value that people are willing to pay a premium for.

You can create many truths from this one starting point. Every tool you use is a way to find that first thread that will weave the story. Your definition of a brand is one such tool.

The longer I do brand strategy, the more apparent it’s become to me that there’s no single way to get there. Each of these three definitions is an entry point. Somewhere to start. You’ll see that different brands follow different definitions, and in doing so, land in different areas of the landscape.

Your goal is to use (or invent) a definition that gets you as far out into the field as possible.