Every brand has a chance to bend the consumer path away from competitors and toward itself in a new future. This is how.

Stories change a lot more than we realize.

Between decades and generations, our collective ideals around basic desires — money, happiness, health, family, food, technology, you name it — radically evolve.

But like a frog in hot water (supposedly), even radical changes are imperceptible to us while they’re happening.

- ‘Marriage to survive’ becomes ’Marriage for love’: Dating in America is only about 100 years old. Before that, marriage was a socioeconomic means to survive. As civil institutions proliferated to create mass economic security across the U.S., the notion of marriage came to be newly infused with the concept of romantic love.

- ‘Cold hard cash’ is suddenly ‘The abstract money concept’: 1950s consumers couldn’t dream of today’s norms — paying with cards, borrowing freely, a new crypto currency frontier — because money had inextricable rules that dictated how and when you spent. Money was in the purview of the government, not outside of it.

- From ‘Working life’ to ‘Life’s work’: As recent as the late 20th century, jobs used to be something you did outside of real life. Today, we live within the cultural construct of the ‘career’, and your career is your waking identity. Even the lifelong mono-career spent climbing the corporate ladder at a single company is being supplanted by a new hyphenated, multi-part career ushered in by the creative class.

It’s not just the systems that change, but our engagement with those systems as well.

With every new cultural narrative comes a new human experience.

When stories change, so does our reality… and this has happened over and over and over again since the beginning of humankind.

Collectively, we call these different eras of thought and belief the Emergent Story Arc.

Your brand can be a part of the Emergent Story Arc, or work against it, but every single smart brand poised for success is making a very clear and risky bet on where the trajectory of the story arc is going.

Brands that matter place bets on the future.

… and they use their brands as signals to push consumers toward that specific future path.

(I talk more about placing your brand bets here and here.)

So how do you draw out the Emergent Story Arc, learn from it, and bend it to your brand’s advantage?

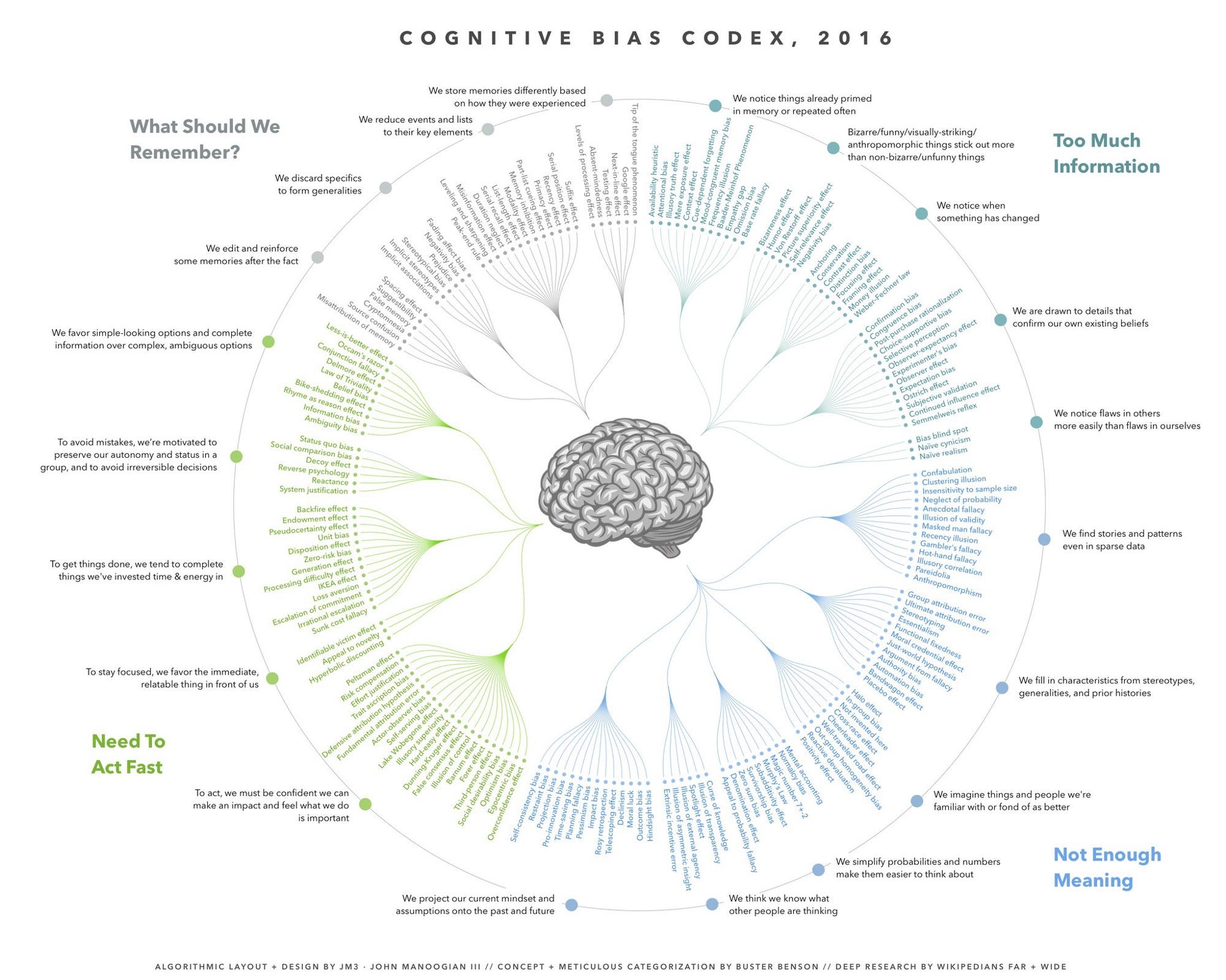

You start by looking for patterns.

Building The Emergent Story Arc

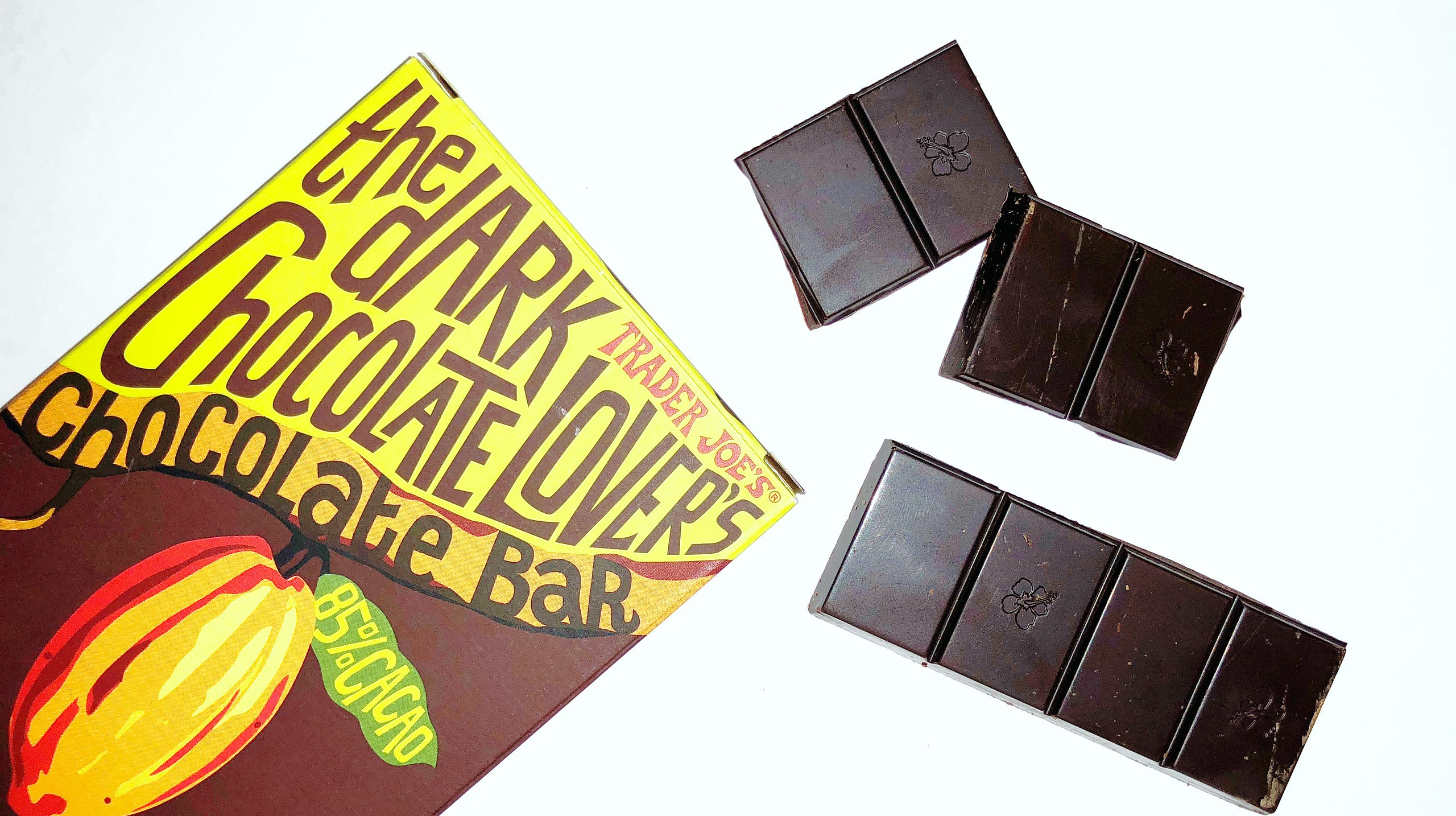

Let’s look at a very basic story that affects all of us — food.

Let’s also assume we are a food startup that has created a chocolate candy bar that’s actually fortified with 50% of your daily vitamins and minerals.

It’s called the Chocolate Happiness Bar.

Imagine Snickers, if Snickers doubled as a vitamin.

The questions we must then ask ourselves stem from the concept of food, snacks and health in everyday life, such as:

- What is the story of food and snacks in America? How do we define it today, yesterday, and likely tomorrow?

- Over time, how has our cultural understanding of food changed not only how we think about it, but also how we consume it, package it, talk about it and gather around it?

- How has our understanding of health changed over time, and how have food and snacks adapted to the health ideal?

- What role does food play in our lives? What stories do we tell ourselves about it?

- What major brands, advancements and beliefs have shaped those stories?

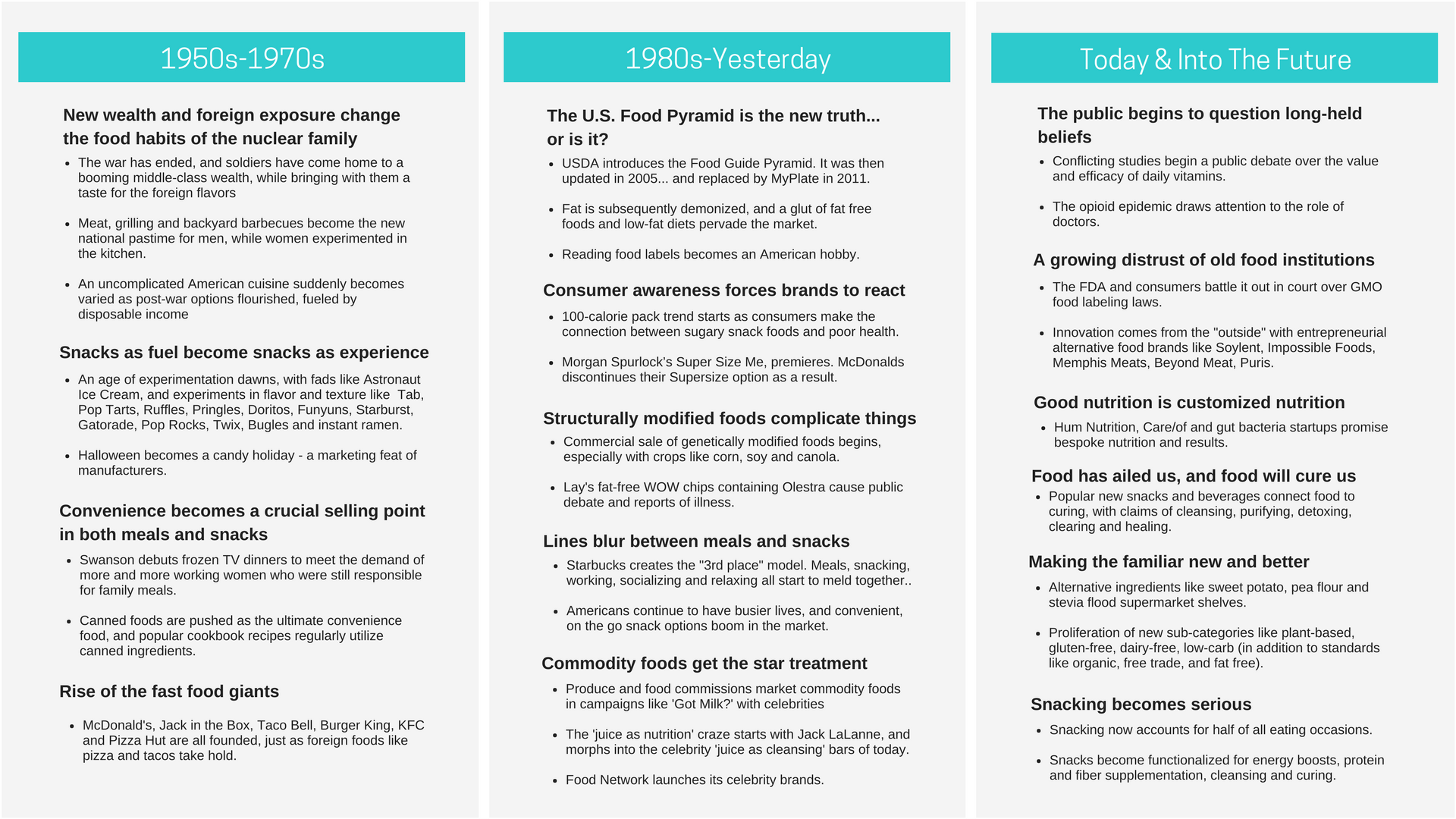

If we looked over all of these considerations over the past few decades and created a 3-part Emergent Story Arc, this is what the first iteration would look like:

In each era, we see that beliefs, attitudes and behaviors changed.

Sometimes brands created those changes. Other times, they were reacting and adapting.

If you go through the points in each era, you can start to see how the overall perception of food, snacks and health have evolved — and how all of those evolutions are interconnected.

It’s in the connections between consumer eras that we start to understand what makes an industry move forward.

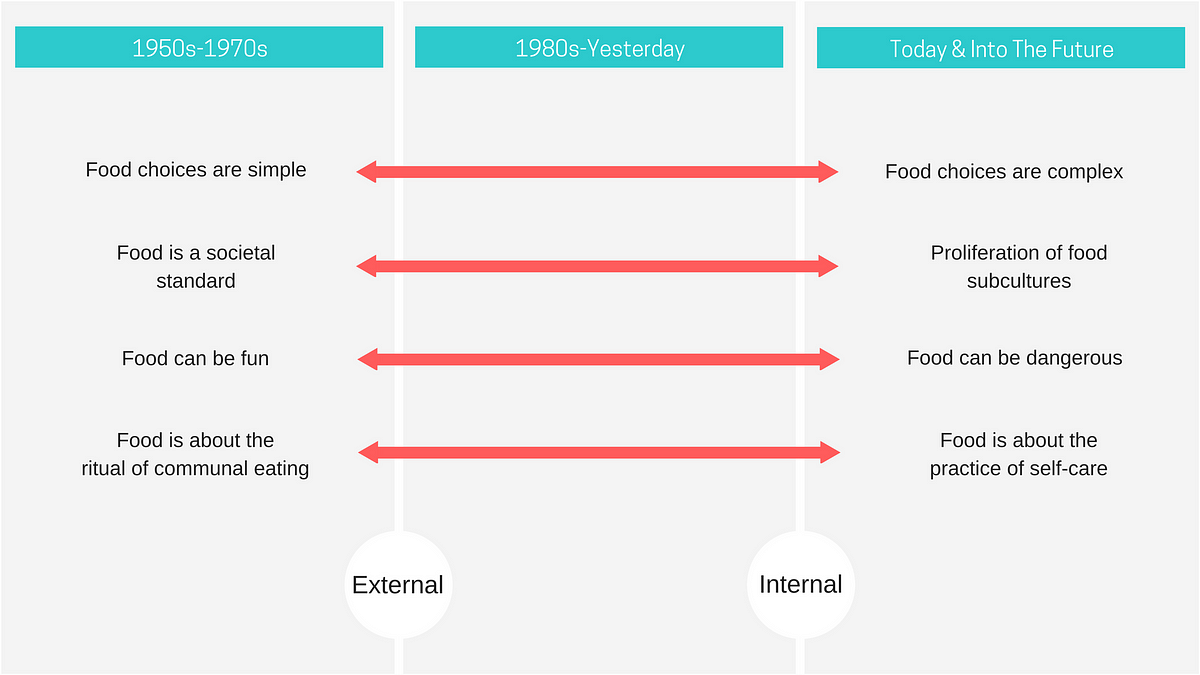

If we zoom out and take a look at what all of these data points are telling us, we start to see some extremes emerge… and between those extremes, some very important patterns.

Food, snacking and health have all gone from external activities and beliefs, to internal ones.

This second iteration of our Emergent Story Arc show us what is buried in the details.

The emergent story of food is increasingly within us. It is inward facing. It is personal, it is private, it is intimate.

Food has gone from a relationship we had with our peers and communities, to a relationship that we have with ourselves.

Our beliefs around consumer advocacy, personal health, and the ‘buyer beware’ mentality that causes each of us to spend hundreds of hours reading ingredient lists and pop health articles all support this.

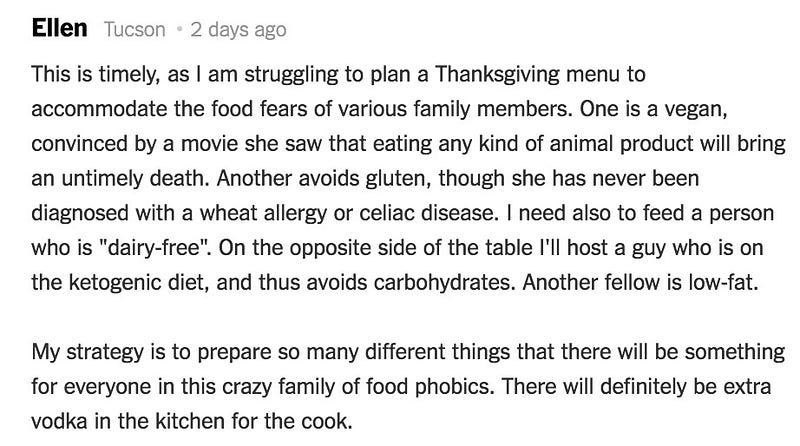

You may have come across a perfect culmination of this mental shift last Thanksgiving when a frustrated host sent a letter to New York Times columnist by Aaron E. Carroll:

This Thanksgiving wasn’t defined by external societal standards. It was defined by internal, personal beliefs — both emotional and logical.

This change in perspective also underscores the surge in snacking over the decades.

Meals are something we expect to do with others. Snacking is something often done alone, between places and events.

Snacking is a largely private event.

As our attitudes about food have moved inwards, so have our habits around it.

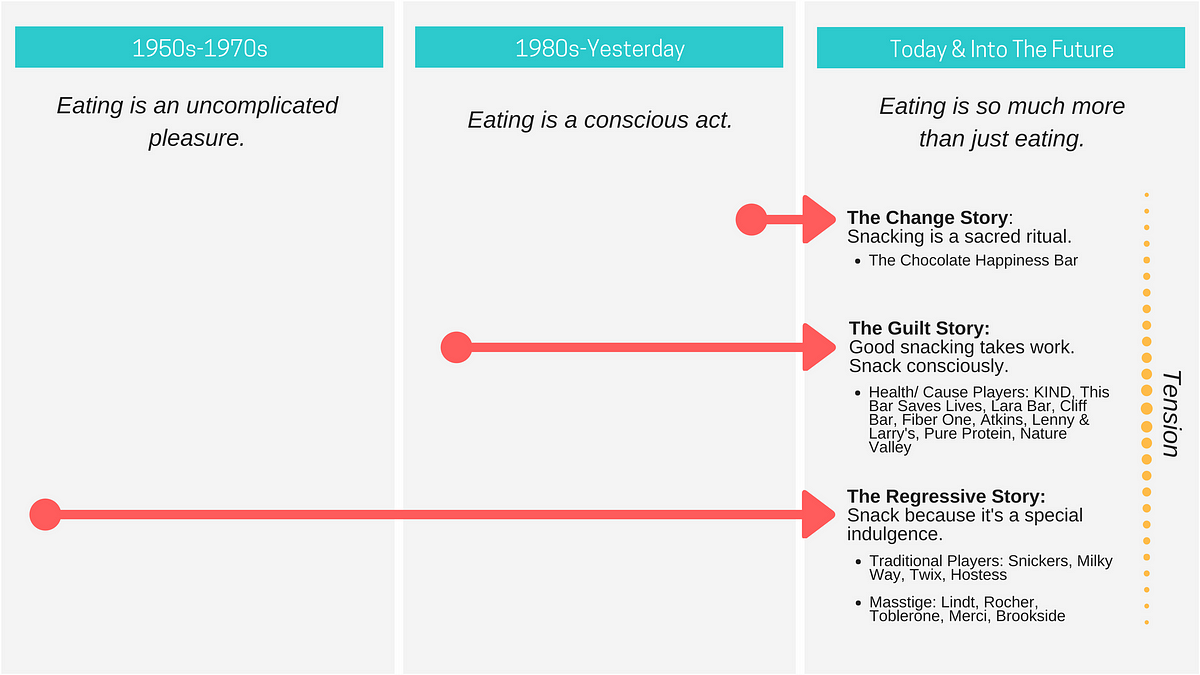

Knowing all of this, we reach the final iteration of the arc where we outline the pervading stories of each era, and then plot our competitors along the future arc to find opportunities for our own brand.

Let’s return to our Chocolate Happiness Bar and see what this new chart looks like.

You can define your competitors however you like, but in this example, we will define it as any single-serving chocolate flavored snack that can be found at the common grocery store — including those that compete with us along the health metric (protein bars, diet bars, fiber bars, etc.).

Here we ask ourselves, what is the dominant story in each time period, and what new stories are on the horizon today and into the future?

You’ll notice a few things about this final iteration of the Emergent Story Arc:

- The future story splits into three different narratives. That’s because we’re living it, and the dominant narrative hasn’t been written yet.

- You’ll notice something very interesting happening here. Both the Guilt Story and the Regressive story actually originate from previous eras of consumer thinking that are no longer prevalent (!) This shows the lack of smart branding innovations in the space, but also highlights something very important for any company: You may find that some of your competitors today don’t really seem to have a POV on the future, in which case you may want to reconsider if they are even competitors. Having a POV on the future is making a risky bet, and like I said at the top of this article, every single smart brand poised for success is making a very clear and risky bet on where the trajectory of the story arc is going.

- The further your story arc diverges from another competitor, the more tension you are creating… and that is a good thing. I’ll explain in a moment.

The real beauty of this arc is that it tells us how to position ourselves in order to be different, not better (because if you’ve read my work, you’ll know better is a losing game.)

Your positioning should answer the consumer question, Why should I care?

Because snacking is a sacred ritual.

That POV is a strong brand position to come from.

You can see from the arc that it diverges from the rest of the pack, while directly speaking to future forces like the decline of family meals, the inward nature of modern food habits, food as healing, and the growing abandonment of old rules.

From here, we can start to build something interesting.

The Emergent Story Arc will tell you what decisions to make

For me personally, building a full arc for a category can feel like being lost in the woods. But once it’s built and the full forest is in view, I can hear it whispering to me.

The arc will reveal opportunities you can’t see when you’re on the ground.

In this example, even though high-level, we are already getting some strong messages from the arc:

- We need to elevate snacking to be the sacred ritual we believe it is. That can come across in our branded language, in our customer engagement experiences, and in our partnerships.

- We need to think about where we sell. We have the most tension with the most outdated narrative — that of traditional and masstige candies you usually see in the checkout lane, and it may be a strong strategy to place our products there instead of the health food section.

- We shouldn’t describe our vitamins using dated language like fortified or daily allowance. Not only are these words connected to an old narrative, but they also echo the language of the very institutions the public has become wary of. Instead, we should consider reframing our benefits as restorative, healing and balancing.

- Create a new category outside of candy, medicine or health. All of these spaces and stories are incredibly crowded — and to fall into them would be to lose our own story.

Product decisions must also reflect brand decisions.

If we truly are an internally-facing brand that creates triggers around sacred moments, then an extension of our product line may look like this:

- The ‘Eat Me Before Bed’ Chocolate Happiness Bar: with vitamins and supplements to enhance the sacred ritual of sleep

- The ‘Eat Me Before The Meeting’ Chocolate Happiness Bar: with vitamins and supplements to enhance focus during the sacred ritual of work

- The ‘Eat Me On The Way To Work’ Chocolate Happiness Bar: with vitamins and supplements to increase energy during the sacred ritual of travel

Again, referencing the future trajectory of the consumer mindset, we know that customization, functionalization, and internalization can be creatively applied here in a candy format in order to place our bets on the future.

Every story changes.

You will find an emergent story arc in everything from the nuclear family and higher education to gender norms and beauty.

We are seeing every institution around us morph into something quite different, and at a faster and faster rate.

…but that presents a wealth of new opportunities — especially when it comes to your competition.

Look for signals and win the war.

See where your competitors are going.

The more they invest in a direction, the harder it will be for them to change it. That’s your advantage.

There is always a higher path to pursue.

The Inputs Always Matter

The inputs for any framework matter. Here are some best practices for this one, that will help guide you in the right direction:

- Go as far back as it matters. I like to cover the formative decades of every living generation, but you may want to go back centuries if you feel it will reveal something even deeper in the human psyche.

- Remove all judgement. What may have once seemed backwards may now seem right-side-up. If you judge people’s behaviors, you won’t be able to learn from them.

- You can (and should) go back to that first iteration and find new patterns. You can rebuild this and it will create a different story arc for the same space, and every version is important. Note that I’ve excluded medicinal competitors like vitamin gummies, but if this were a larger arc with more layers, they would be included.

- Pay attention to which things have carried throughout the length of the arc, and which have emerged and disappeared as fads (…100-calorie packs are decidedly on their way out).

Build Something That Takes Us Somewhere

You have to start at the mouth of the river in order to understand where it’s going, how fast it’s going, and how likely it is to overflow and change direction.

“I see the future as a series of branching probability streams. So you have to ask, what are we doing to move down the good stream?”

You’re building a company around a theory that will take us into the future.

Theories come from observation of patterns. I hope this framework gives you the tools to surface those patterns and act on them.

We will always follow those people who can imagine a future so vividly, that they practically guide us there from the here-and-now.