3 moves you need to be making right now.

Brands emerge from choices.

A brand isn’t your website or tagline. It’s every decision and action you take, and the meaning that emerges from those activities.

Brands occur between the lines. When you consistently make on-brand decisions about your sales, operations, communications, UX, product development, CSR, partnerships, new markets and new hires, you are demonstrating a commitment to a larger belief.

If people can find a common and compelling thread among those choices, then you’ve successfully brought a brand to life.

But the kind of brand you are creating is a different story.

There may be a common thread, but if the thread is mundane or unimportant, it won’t travel far.

The Italian coffee shop at the airport is highly branded with a voice, set of service principles and beautiful aesthetic, but I will still pay more for inferior coffee at Starbucks because the Starbucks brand taps into a larger belief about work and connection.

A compelling brand takes risks.

Risks are decisions just like anything else you can spend your resources on at your company, but I would argue that taking risks is one of the most important things you can do.

I recently took an Instagram poll asking people to choose from topics in the world of branding that they’d like some discussion on… and risk taking was the clear winner (follow me on Instagram to be a part of the next poll.)

I’ve written about brand risks extensively, from having a POV on the future and resisting the temptation to be better, to alienating non-targets and creating tension.

There’s an infinite world of calculated risk out there for any company to navigate, but there are a handful of decisions that most companies would benefit from making right now.

1. Tell the story you don’t want to tell.

Every entrepreneur I meet has two versions of their story — the version they tell, and the version they hide. The job of brand strategy isn’t to bury the less glossy story (or what some may call the truth).

Good brand strategy takes the whole story and makes meaning out of it.

I was in Tokyo recently where I met a fantastic Chinese fashion startup, and although they had created a phenomenal product with a phenomenal team and bold ideas about the future, they were conflicted on what to do with the fact that their materials were created in China.

Although they took great pride in the heritage and quality of their textile facilities, the origin story troubled them.

I could understand. Chinese manufacturing, especially in high-end fashion, has very clear and negative connotations in markets like the US.

My recommendation was to turn around that Made In China stereotype and actively own it. Define a new wave of manufacturing in the country that was emerging from the ruins of the old guard, and use PR and content to position the fashion brand as the figurehead for a fascinating textile manufacturing renaissance that was just emerging in pockets throughout the country — including their own plants.

I’ll admit, that wasn’t easy advice to take.

It’s a huge risk for any brand to try and overcome and reverse decades of belief about its country.

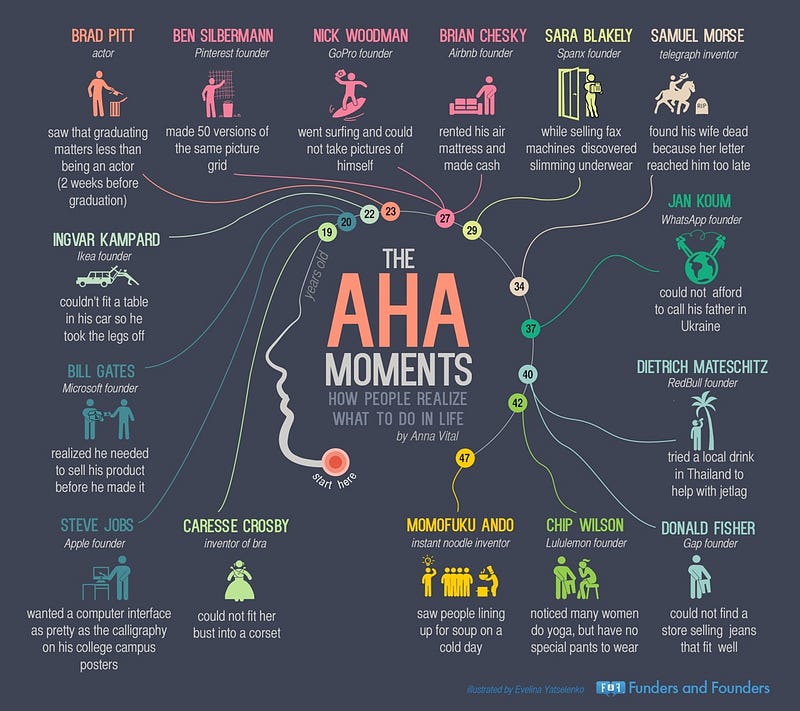

But it was the right risk, and the only risk worth taking. In some regards Ikea has done it. Samsung did it before them. Not taking that risk is a bigger potential pitfall than taking it.

Another consultant the company had spoken to suggested they avoid the Made In China fact, citing the cultural difference between America and China. It was her belief that the two countries have different value systems, and making one care about the other’s was an impossible task.

First off, no. A smart brand willing to take a risk can make people care. That is what brand strategy, at it’s most basic level, is supposed to do.

This is what I do for a living, and I can tell you that the craft of changing consumers’ hearts and minds is no different for big challenges as it is for small small challenges — you change the story in order to own it.

Secondly, if you don’t own your entire story, then someone will use it against you.

Even worse, someone else will turn Made In China into a valuable asset, and that opportunity will be lost for your brand.

Every time you are faced with a liability, find a way to turn it into an asset.

Tell the story you don’t want to tell.

There is a way to make it work.

2. Show your face.

If you’re a CEO, you don’t need to be the face of your brand, but you do need to show your face (figuratively, not literally).

Accountability, transparency and humanity aren’t features anymore. They’re baseline expectations. At the very least, you‘re expected to make your brand honest.

Honesty means a lot of things, from customer support best practices to checks and balances in the value chain.

But nothing signals honesty the way an accessible leader can. To hide behind a brand name and pretend the CEO is not a public figure is a copout.

As I’ve said, every decision is a building block in the foundation of your brand, and the decision to not show your face as the founder or CEO is to say that the brand doesn’t have a human behind it.

Customers need to understand that the buck stops somewhere. That there is a person who is willing to be accountable.

Showing your face means you have the guts to stand behind what you’ve created.

It’s a risk. Of course it is. When shit goes sideways (which it will) your face is the one people will be coming after.

As a leader, that’s the job you signed up for.

But taking ownership of the company, good or bad, always pays off. I have seen this time and time again, no matter the size, stage or industry of our clients.

Tell your individual story as it relates to the brand, personally seek out feedback from customers, blog about your beliefs and steps forward in the industry, and be willing to engage in public conversations with other stakeholders from time to time.

If you’re shy, if you’re modest, or if you’re like many of my clients and are just uncomfortable with the idea of being known, I’d encourage you to do some soul searching.

You started your company for a reason. There’s nothing wrong in taking ownership.

People want to know exactly what (and who) they are putting their trust in.

3. Find a white space for the brand, not just the product.

Ah, the landscape axes. A fundmanetal slide in every pitch deck.

Love ’em or hate ’em, if you’re actually honest about those axes, they can reveal some powerful opportunities.

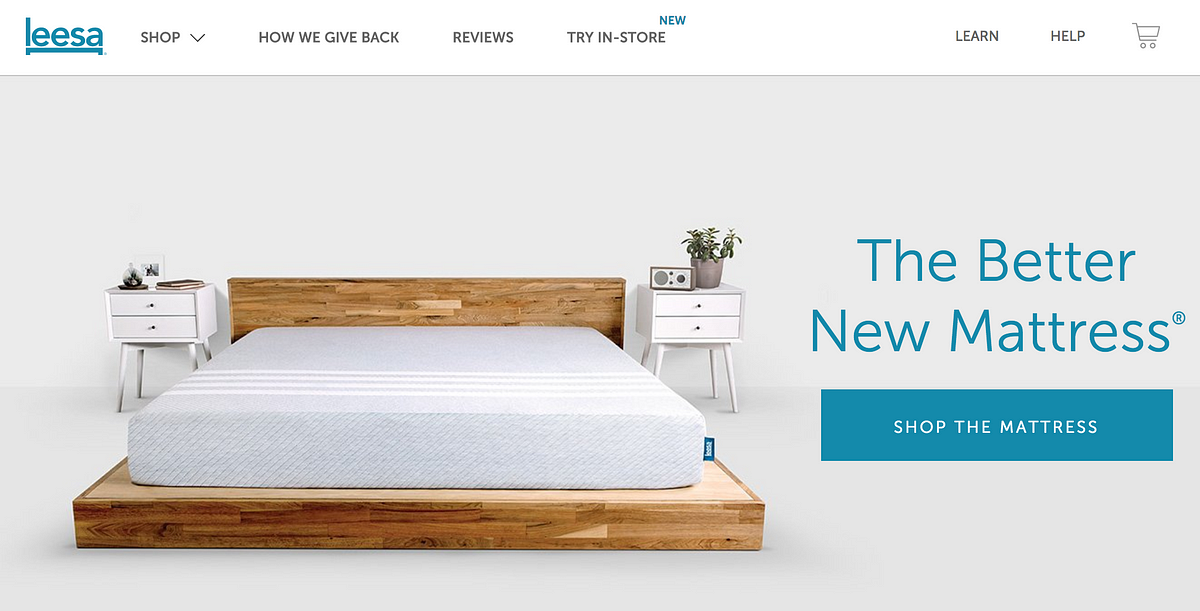

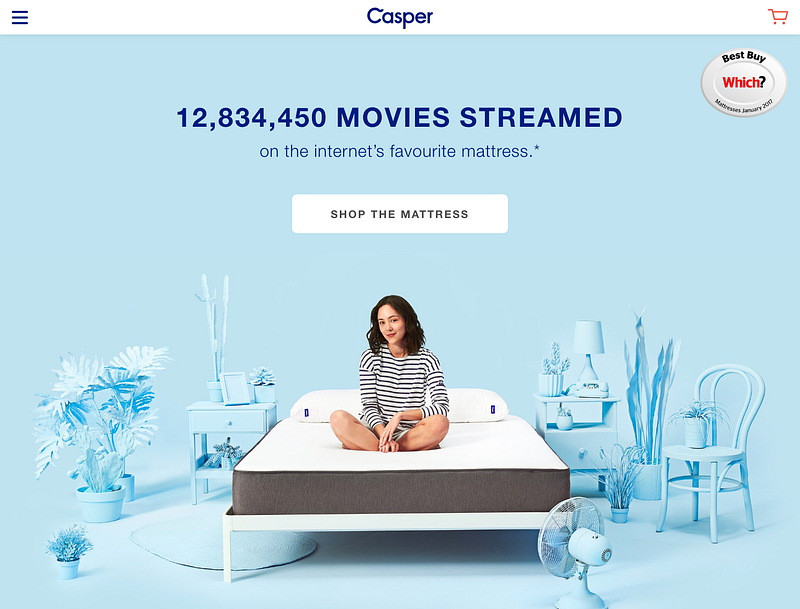

I find many entrepreneurs create them for their products, but very few actually look at the landscape for their brand identities as well.

Your product sits against a set of feature/ benefit axes, but your brand sits against narrative axes: the stories that are being told in the product playing field.

Just as with product, the axes you choose will drastically effect the placement of you and other relevant players. That’s why it’s important that you choose wisely.

When looking at which brand axes to plot against, ask yourself these questions:

- Where do the prevalent stories in the space start to diverge from the behaviors of our users?

- Which narratives do we take for granted? Which narratives are ready to be challenged?

- Which stories are so entrenched that they go unquestioned in the space?

- What stories have become so big that the competitors who tell them will have a hard time straying away from them?

- What stories can our competitors not tell?

The story you tell should be defensible and difficult for your competitors to follow or co-opt. That’s exactly what this set of questions is designed to uncover.

It can feel risky to look at your brand in a competitive environment, because for the humble founder it’s oftentimes hard to see the brand as more than just the sum of it’s products and features. But that’s a mental trap.

Your brand should measure up to more than just the sum of your products and features.

If products + features was enough, Starbucks wouldn’t be beating that Italian coffee shop at the airport.

If actions speak louder than words, then every move your company makes is a brand signal.

One of the most important signals you can send is that you are willing to take risks. Risk is rewarded in the consumer market, and the most important risks lay in the bedrock of your brand identity.

Every risk taken is a brand signal sent.

Be bold and show people that what you say is almost as important as what you do.