This is what the business of identity looks like.

If you want to know the values of a culture, look at its language.

In America, we’ve come to talk about time through a very distinct metaphor hiding in plain sight:

- Can you spare some time tomorrow for a quick chat?

- Let’s make this worth our while.

- I’ve invested a lot of time in this project.

- Thank you for your time.

- Don’t forget to save time for the Q&A.

- Use your time wisely.

In American culture, time is a valuable commodity as pointed out by George Lakoff and Mark Johnson in their fascinating book Metaphors We Live By. You don’t see this in the languages of other cultures like those in the Middle East or Africa because their cultural values are markedly different than ours.

In this country, time is quantified. It is saved, protected, counted and measured. Just like money.

That’s because of how our concept of work evolved in the US. We pay people in hours, we rent hotel rooms by days, budgets are created annually, interest accrues over months and so on.

When we treat time like money, we give it the same inherent qualities and meaning. It takes up the same space in our heads as money does, and I’ll stress again that this is not a universally human concept. It is distinctly western and borne of our modern relationship to work.

Our words betray our history. Our common metaphors and devices map us to our shared evolution over time. What we say is tied to who we were.

You can see the same relationships in other places, too, like our use of war terminology in everyday vernacular in the U.S. to the new text and emoji languages that have sprung from the mobile screens in our hands.

Language is something we live inside of. You simply cannot separate it from the human experience.

Language can bring us close and at the same time throw us into discomfort. If you’ve ever read Faulkner’s The Sound and the Fury, where the first person narrative of a mentally disabled protagonist was told through a stream of consciousness, you understand how quickly language can destabilize you while pulling you into a completely foreign world.

It has the capacity to change how we see our own bodies. In a recent profile of Loom, the ultra popular health education center in Los Angeles, a student stumbled upon a linguistic relic many of us have overlooked as women, but founder Chidi Cohen has not:

At the end [of the class], she passes out a variety of vibrators, anal plugs, and lube so that her students can feel their rumble, weight, and viscosity, respectively. […]

“You don’t stretch out?” someone asks, eyeing an enormous mint-green phallus.

Chidi Cohen lights up. “That’s a wonderful question,” she says… The idea of tight and loose is, again, really patriarchal. Exactly the type of junk we’re trying to dismantle.”

(emphasis added)

Language like this is so deeply embedded it escapes our noticing, but it always leaves a fingerprint behind.

This same interplay between words and identity is happening in business as well.

You may not realize it, but new cultural values are seeping into nearly every industry by way of the words we use, effectively shifting our relationships to our peers and ourselves.

That’s no small thing. It’s opening up new opportunities for brands and categories that weren’t viable before, making branding itself about so much more than product.

If you’re a founder, you should realize that above all else, you’re in the business of identity. Your words and your messages (written or otherwise) are all pulling from a living language that defines who we are.

In fact, the language of every medium is going through a renaissance right now, but when it comes to business, some especially interesting changes are taking place.

The Language of Extremes: A New Relationship With The Other

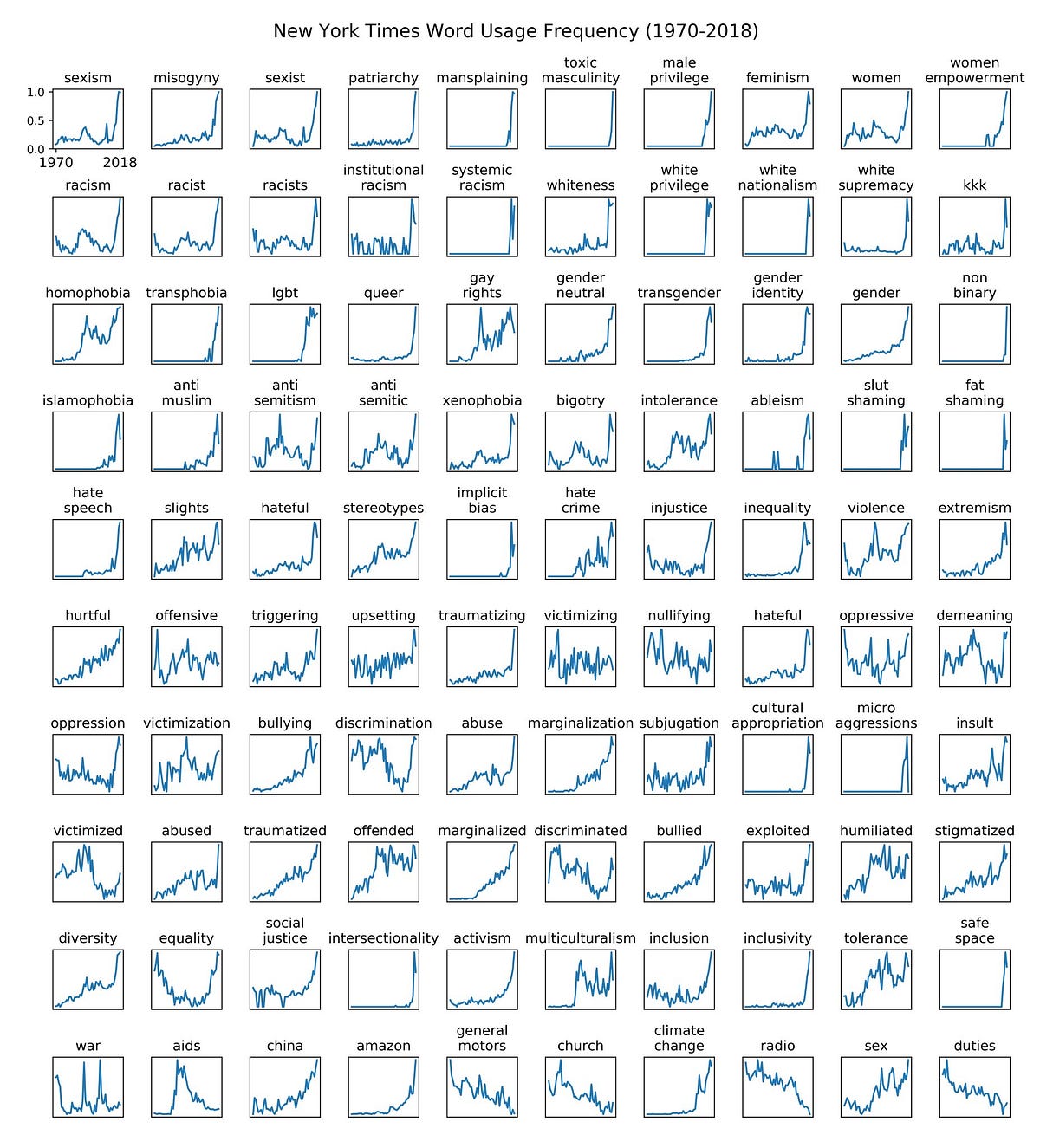

This chart, created by researcher David Rozado, tracks word usage in the New York Times since 1970.

There’s something happening here and different people have different opinions on what that is. Rozado, the researcher himself, sees it as a “peek at shifting moral culture.”

Others, like VC Paul Graham, saw it as a reflection of the news industry’s subscription model and the need to skew politically in order to win an audience:

Hypothesis: Although some newspapers can survive the switch to online subscriptions, none can do it and remain a politically neutral "newspaper of record." You have to pick a side to get people to subscribe. pic.twitter.com/bWNZzYFzFJ

— Paul Graham (@paulg) June 7, 2019

The most interesting insight, however, came from my twitter friend Zach Shogren who pointed out that many of these terms didn’t even exist a few decades ago. Those that did exist had a completely different significance.

To be fair, a lot of these terms weren't around 30 years ago. Not the way they are used today at least.

— zach shogren (@not_zachshogren) June 11, 2019

It’s a huge emotional burden to carry these words in our everyday language, but many (including myself) would argue a necessary one. We hear them and we ask ourselves if these words encompass us or not — if they perhaps encompass those we know or those we don’t.

Terms like triggering, micro aggression and cultural appropriation allow us to see actions that were always there, but imperceptible to us in the past. Other phrases like implicit bias, fat shaming and white privilege codify things that we have always felt, but could not fully name or explain. These words make the invisible visible. They force a new field of vision whether we like it or not.

When you can articulate human experiences that you didn’t have the words for before, you’re creating a dichotomy of 1) intimacy through revealed experience, but at the same time 2) an otherness that demarcates yourself from your peers.

Does that dichotomy sound familiar? It’s the dichotomy of tribes.

We all know about the concept of tribes in marketing thanks to Seth Godin’s genius, but what’s interesting about our new language of extremes is that it points to an evolution in how tribes operate.

Our most vibrant modern tribes are not about shared interests. They’re about grappling with who we are. And we’re inventing terms as part of that exploration.

Many strategists and marketers talk about how tribes are connected to a larger altruistic belief about how the world should be, and in some cases that may be true, but the most powerful tribes of today help us form a culture around the questions of identity.

Certain brands, and their tribes, know this.

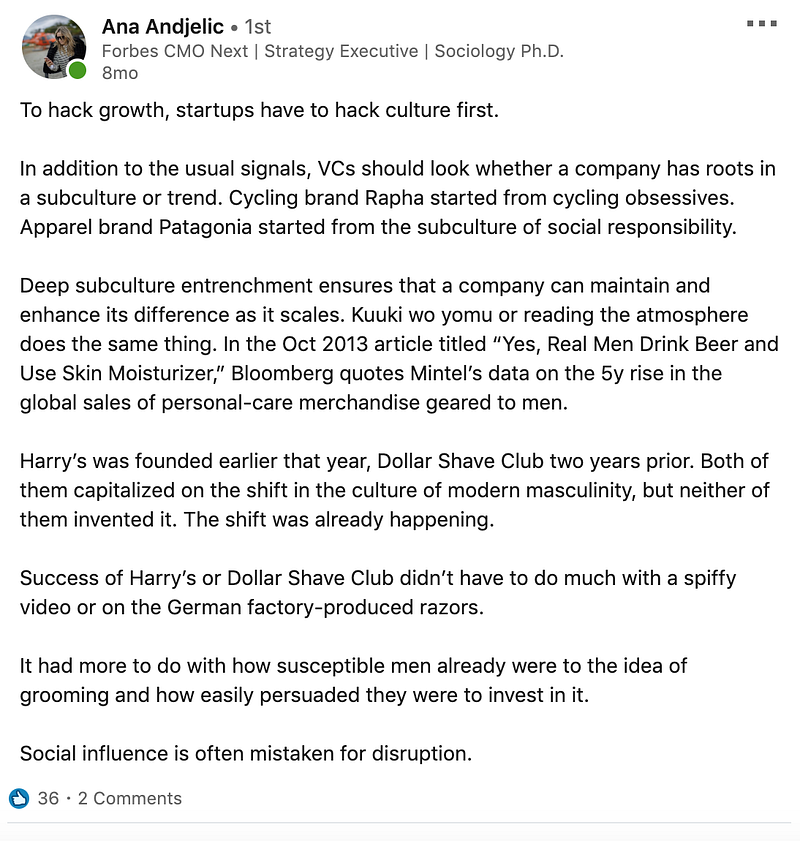

As the brilliant brand strategist Ana Andjelic has pointed out, many of the influential brands we call disruptive are actually defining culture, not disrupting an industry:

Yes, social influence is the real disruption, and language is a leading indicator of where the social signal is headed.

Patagonia, Harry’s, Dollar Shave Club — they burrowed themselves within a subculture and grew it into a mainstream vehicle for identification.

You don’t buy Rapha because you have a shared interest in cycling. You buy Rapha because you want to see how far you can push yourself physically, and that originated in a subculture mentality.

Rapha, in the macro, is making a comment on identity. Not just any identity, but the hyper specific identity of their tribe.

They’ve seen the language in the landscape, either through words or cultural touchstones, or any other number of communication mediums.

That New York Times chart is telling us that our identities are top of mind for us as a culture. We are moving in a million different directions trying to figure out who we are by way of our extremes.

If this new language is about defining ourselves by defining the other, then brands are a framework for turning that language into a conversation.

The Language of Wellness: A New Relationship With The Self

Self-care is a miraculous term because it has completely changed our relationship to our bodies and ourselves, especially for women. But it comes from very, very deep roots in marginalized communities, and later the civil rights, women’s, and LGBTQ movements of the 1960s and 1970s.

According to professor and writer Jordan Kisner:

The scholar Matthew Frye Jacobson points out in his book Barbarian Virtues that immigrants arriving to the United States from Southern and Eastern Europe in the late nineteenth century were deemed “unfit citizens” because they lacked the “ideas and attitudes which befit men to take up . . . the problem of self-care and self-government.” The same arguments were made to deny women the vote. Consequently, self-care in America has always required a certain amount of performance: a person has to be able not only to care for herself but to prove to society that she’s doing it.” […]

In 1988, the words of the African-American lesbian writer Audre Lorde became a rallying cry: “Caring for myself is not self-indulgence, it is self-preservation, and that is an act of political warfare.” In this formulation, self-care was no longer a litmus test for social equality; it was a way to insist to a violent and oppressive culture that you mattered, that you were worthy of care. Lorde’s quote remains the mantra of contemporary #selfcare practitioners.”

(emphasis added)

Self-care, remarkably, comes from a wildly different place than you’d expect, but in America has always carried the tension between doing something for oneself versus doing it for an audience — a tension between being run into the ground versus carving a safe space for yourself.

After 9/11, the concept of self-care started to get louder in the mainstream consciousness and after the 2016 election, reached a fever pitch by way of the “the grand online #selfcare-as-politics movement”.

Except by then it was no longer driven by the marginalized people who founded it, but rather by affluent white women — the kind you often see on Instagram who popularized the version self-care you may be familiar with today — who felt “a new vulnerability in the wake of the election”.

Self-care is a term that’s permutated between fear, strength, politics, personhood and cultural appropriation. The most authentic version of the phrase is not a marketing gimmick. It came from some place real.

That’s why it has been so powerful in changing our behaviors.

- Self-care and sex: Today, you can find sex toys like PlusOne in Walmart (Walmart!) because they have been rebranded as self-care and sexual health tools for women. They’re right there, sitting next to the yoga equipment.

- Self-care marijuana: CBD and marijuana are experiencing a golden age of adoption under the term self-care and wellness. It’s hard to say if increased legalization created a new narrative or the other way around, but it most likely worked both ways as changing attitudes and stories helped tip the balance of law. Gossamer, Dosist, Beboe and countless others have mushroomed in the D2C landscape under the consumer spell of self-care.

- Self-care and beauty: Beauty is going through a huge boom in large part because we’re no longer using skincare just to look good, but to feel good, too. Ask any number of beauty CEOs from companies like Milk Makeup and Glossier and they will tell you that beauty is about having an experience that makes you feel empowered and strong.

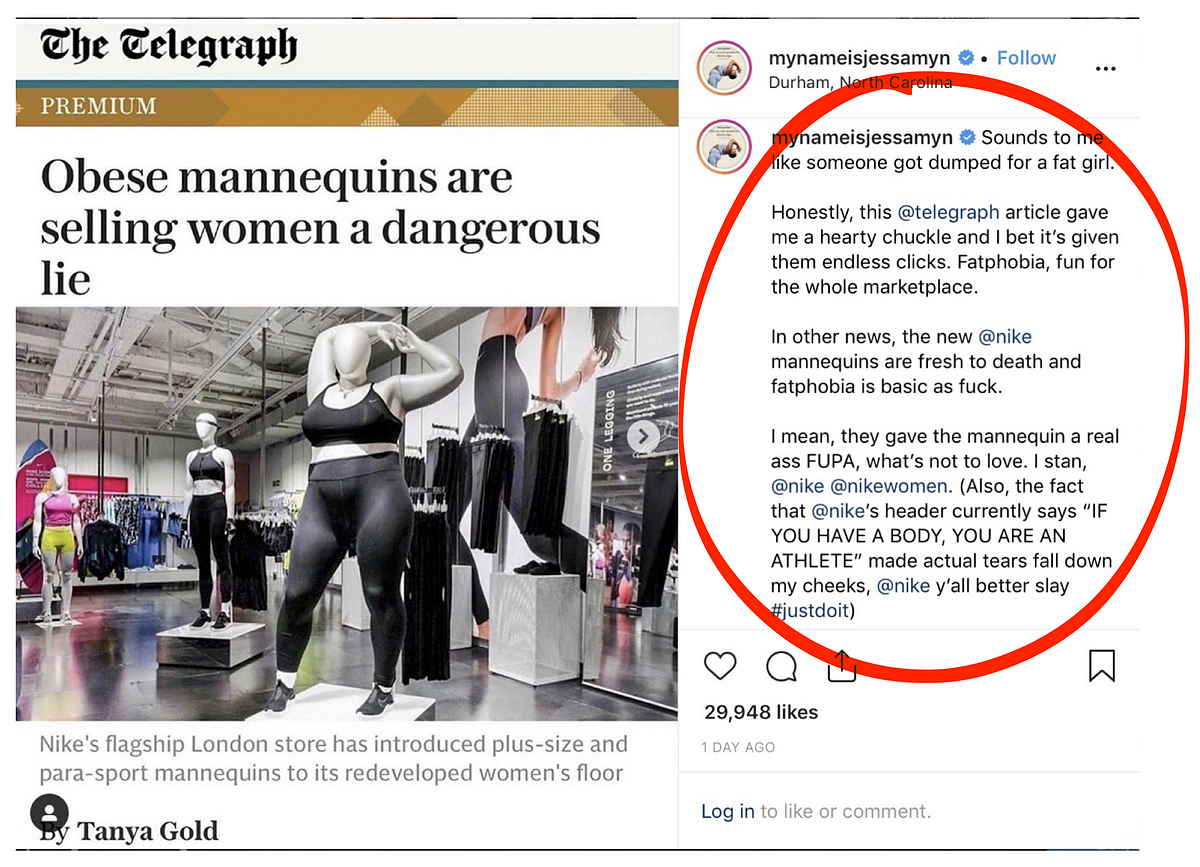

- Self-care and fashion: Sports brands and athleisure companies have had tremendous success selling the idea of wearing their clothing when you’re not working out. Meanwhile, a brand like Nike, who has a long heritage of fetishizing the lean, athletic body, is able to successfully spearhead discussions at the other end of the spectrum around body positivity, fat shaming and ableism.

Why have all of these industries blown up under the wellness umbrella?Because self-care has given us permission to look at ourselves differently, touch ourselves differently, relate to ourselves differently… all without saying SEX, DRUGS or VANITY.

It has created both a literal language and an experience language that’s opened up entirely new industries and audiences.

Everything means something.

Language is the most powerful brand tool you have. Whether your use it in conversation, listen to it for signals or map it back to a hidden meaning, it will always give you more than what is on the surface.

Any of these insights can be applied to industries I haven’t mentioned, and many other doors can, and will, be opened through the language we use.

Everything means something. Don’t choose your words lightly.