If your product is a community, or your community is beginning to become the product, you are already living in the future of Strong Ties.

And in this future we need new rules for brand strategy.

Weak ties historically allowed us to extract value from the peripheries of our networks (think LinkedIn, Instagram and Twitter), while strong ties extract value from relationships at the center of our networks (think Patreon, Polywork, and the proliferation of like minded living communities).

This is a massive shift considering that weak ties have been the underpinning of social innovation for the last two decades, and are now declining while strong ties are starting to emerge as the dominant threads of our social fabric.

New social innovation means that any meaningful group will be forced to rearrange itself, whether it’s an online community, a movement, employee culture, subculture, club or cult following.

Strong tie communities tend to have the following characteristics:

- They naturally incentivize going deeper with smaller circles of people, rather than going wider with larger circles of people.

- They prioritize innovation in how people connect, not how many people they connect with.

- They allow members to individualize themselves instead of forcing them to standardize themselves.

- They give members true ownership, either through literal shares and coins, or by giving them the power to shape the group culture, norms and evolution.

When strong ties become the future of community, community becomes the new brand.

This is how to build that brand strategically.

1. If you break an old system, you must create a new one.

Occupy Wall Street, Anti-Vaxx and Anonymous were all communities based on opposing or tearing down old systems. None of them fulfilled their visions.

That’s because old systems leave vacuums in their absence. You cannot successfully remove an old system without replacing it with a new one.

This is why secular congregation communities like Sunday Assembly and Oasis that offered gatherings without god went nowhere, but fragmented spiritual groups like Nuns & Nones and spiritual leaders like Esther and Jerry Hicks or Gabby Bernstein that give safe haven and new systems of meaning to the post-religious, are thriving.

The first group broke an old system. The second group broke an old system and replaced it with a new one.

Many communities – from online groups to movements to even countries – exist in opposition to something else. Yet if the situation or the rhetoric changes, all value and credibility can be lost in an instant.

The once highly buzzed about r/antiwork community, whose tagline is “Unemployment for all, not just the rich”, works to tear down old systems but offers nothing new.

It’s no wonder that r/antiwork lost nearly all credibility when a short Fox News interview revealed just how directionless the community was in their vision for what would replace the current “work” system.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4IfzpgGwHkI

As New York Times journalist Oliver Whang questions, “Hating your job is cool, but is it a labor movement?” It seems the answer is no, it is not.

Scholars increasingly point out that the problem with many community brands is that they demand “the destruction of existing institutions without offering an alternative vision of the future or an organization that could bring it about.”

The winners consistently create new systems to replace old ones.

2. Know why you gather.

If you don’t know the real reason why you gather, you will miss the few, brief opportunities that could take your brand to greatness.

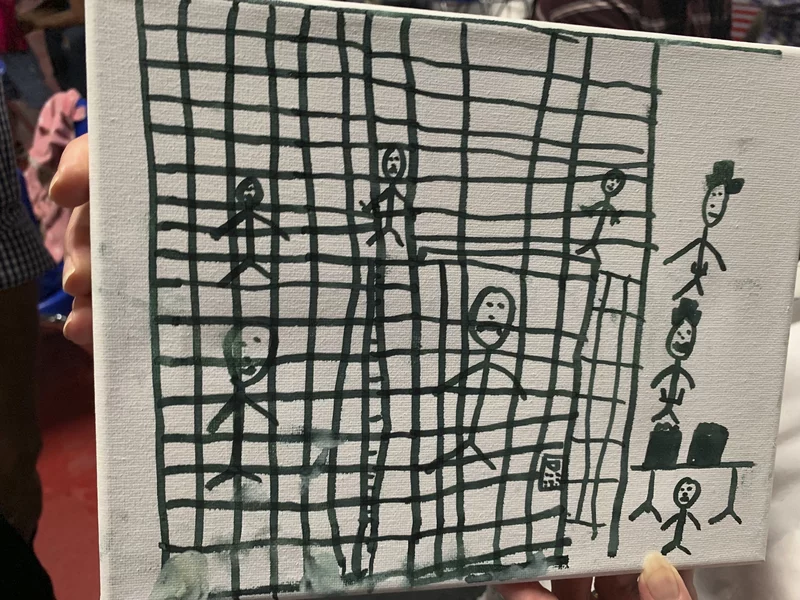

In 2019, when kids’ drawings emerged from a detention facility in Texas where migrant children between the ages of 10 and 11 years old were being separated from their parents, the Smithsonian made the very interesting decision to try and acquire the artwork.

The Smithsonian, whose collection spans Apollo 11 pieces, Dorothy’s ruby red slippers, and the Hope Diamond, is a treasure trove of easy-to-love Americana. But over the years the museum has realized that their people don’t gather to marvel at American history. They gather to witness the humanity of America.

When the migrant children’s drawings emerged, it made sense for the Smithsonian to identify it as a collection of art to gather around. Without really knowing why they gathered, the opportunity would have been lost.

Why you gather has huge implications for how your community’s brand is perceived. Knowing why you gather is the same as knowing how your brand creates value.

It’s a crucial truth that many community brands fail to articulate, and even those that do often lose sight of it over time. Knowing why you gather keeps your brand centered.

It’s the only way to seize landscape opportunities that would have otherwise gone unnoticed.

The Smithsonian said something when they pursued the artwork of migrant children at the center of a political firestorm and America’s reckoning with its own sense of humanity. And the people that will hopefully one day gather around those drawings will not only know why they are there, but feel where we have been as a country.

3. Embrace optimism.

Or perhaps more accurately, resist pessimism.

As Nat Friedman has said, “Pessimists sound smart. Optimists make money.” This is true in community branding as well. Pessimistic communities may attract attention, but it’s the optimistic ones that grow and prosper.

Most anti-capitalist groups go some distance on pessimism, but communities like FI/RE or Fat FI/RE run much further on optimism. The perceived merits of each community notwithstanding, it is clear that optimism mobilizes people toward a shared goal much faster.

Optimism is especially important when it comes to employer branding, both within the company culture and in attracting ideal talent.

In my own work and research I’ve seen that truly optimistic brands lean on their visions, not their missions, to rally people. That’s because the best talent moves to be inspired, and that only happens when you have a vivid vision of the future that only your community can create. Visions paint the future, and missions spell out the who-what-how of getting there.

In my interviews with high level talent for employer branding, we consistently see sought after talent be drawn to visions, not missions. This group of people wants to gather and grow around an optimistic ideal and know that in their short time to make a difference in the world (and just as importantly, in their careers) they will be aiming big enough to do something that matters.

Companies that lead with mission tend to focus more on making their audiences happy (missions usually speak to customers and can leave out employees entirely). Making a subgroup of people happy is not the same as changing the world.

Why are cults at an all time high around the world, especially in first world countries, despite education and socioeconomic background? Why do crypto, DAO and NFT communities refuse to die, despite countless news cycles calling the end of these movements?

Because there is a deep seated, stubborn optimism baked into the DNA of those communities and their brands that will not be destroyed.

Yes, even cults are driven by optimism, as cult expert Amanda Montell pointed out in my interview with her:

“The ultimate fatal flaw across all cult followers from folks who joined the Heaven’s Gate, the nineties suicide cult, to folks who strike up with multi-level marketing cults, in scare quotes, was yeah, not desperation, but optimism. This overabundance of idealism, that the solutions to their problems, whether that was racism or classism or for financial insecurity, could be found and if that they affiliated with this group, with this leader, they could be a part of that change. It takes someone really optimistic to sign up for a belief like that…

Optimism that was their Achilles heel more than any of the qualities that the cult documentaries you might watch would lead you to believe.”

Oftentimes that optimism is what carries a young community from near death to new life.

But take care that your optimism doesn’t border on emotional hijacking. Why did this Heineken commercial work so well, while all of those Dove Beauty ads eventually fell to criticism?

https://youtu.be/XpaOjMXyJGk

Heineken gave us a reason to be optimistic. Dove, and the body positivity community it inspired, however, “put the onus on people living in marginalized bodies to turn their criticism inward. This time, though, those people are told not to be ashamed of their physical selves, based on the premise that there was never anything wrong with them to begin with, as though the same companies that claim to be guiding this “movement” haven’t been selling insecurity for years”, according to journalist Amanda Mull.

Communities need optimism, not emotional hijacking. Don’t mine the trauma of your users for an emotional response, no matter how optimistic it may seem on the surface.

4. Surface your vibe.

Perhaps the most primal reason why people gather in communities is because of how it makes them feel, so it’s worth knowing what that feeling is and how you can surface it. Yes, we all want to feel like we ‘belong’ when it comes to community, but you have to go deeper if you want to create a memorable brand.

Vibes and feelings are user heuristics for what the community represents. In a complex world, vibes are an easy shorthand for knowing if a community makes sense or not.

Your vibe is the emotional read someone has on the brand. Lego has a nostalgic aesthetic. Nike has a distinct voice. Airbnb platforms belonging. All of these brands have communities but none of these qualities alone make a vibe.

A vibe makes someone sense something greater than what they see or read.

We’re Not Really Strangers angles everything toward its vibe. Its content, its products, its language, its aesthetic, its Instagram (and Finsta) create the feeling as if we are all waking up from a dream where we forgot how intertwined humanity is.

Quite literally, their content and brand touchpoints evoke feelings of sudden remembering, of recognizing someone you didn’t remember at first. It is a sweet returning to the human race. Yet what they sell is ice breaker card games and inspirational gear.

Vibes activate our System 1 thinking of intuition and knowing. You know a community and brand like We’re Not Really Strangers even before you understand it.

Vibes are tangential to brand relatability, a topic that my Concept Bureau colleague Rebecca Johnson has studied extensively:

“You have to find moments that tap into your audience’s subconscious. It’s about revealing something that exists at the edges of their identity […]

Relatable brands reflect their audiences’ identity in a way that goes beyond the product they’re selling. They reveal and validate hidden truths to which their audiences can connect and relate.”

Creating a vibe requires great intimacy and great vulnerability, two things which only make sense in the new era of strong ties.

5. Memorialize the good and the bad.

TITSOAK and lossporn are both memorials of the communities they come from.

If you are in either of these groups, you know that each term is a phrase of self-deprecation. TITSOAK is an absurd line that Twilight fans laugh at themselves for loving, and lossporn is the people of r/wallstreetbets memorializing the ridiculous losses and risks they endure in their larger quest to win over the system.

They demonstrate that it’s just as important to memorialize the bad stuff as it is to memorialize the good stuff. The good stuff is a great celebration of the community’s successes, but memorializing the bad stuff does something very different.

In relationship science, it’s been found that the way a couple remembers their fights and low points is a huge predictor of whether that relationship will succeed.

People who remember their arguments with anger or disdain tend to have poor outcomes, but couples who laugh about their disagreements and remember them as endearing and valuable moments of growth are far more likely to stay together. They effectively create a story around those moments. That story becomes part of their mythology.

This is no different in communities. Groups that can memorialize their failures with humor, gratitude and pride strengthen the bonds between their people.

The failures, the goofs, the slip ups, the embarrassments and losses – they’re all valuable moments to continue building your group’s mythology.

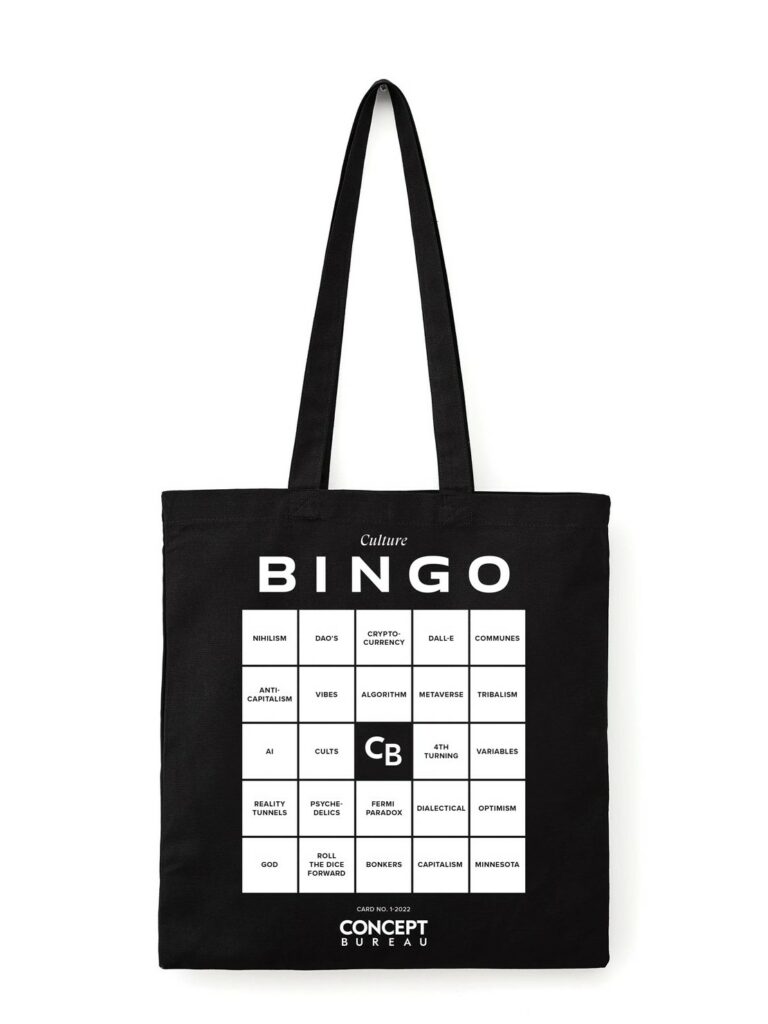

At Concept Bureau, my team laughs at how insular our own thinking can be, and how the same topics keep coming up over and over again no matter where the conversation starts.

So naturally we created an annual bingo card to memorialize our folly. Some of the boxes like “Bonkers” and “Minnesota” reference real slip ups or all-out disagreements.

We now wear that bingo card on sweaters, tote bags and mugs with appreciation for the group.

6. Strong ties or nothing.

Most of these community examples come from organic communities, but what about brands specifically? How do they employ the same levers for building thriving, meaningful community among their people?

There’s one golden rule that can’t be violated: a community brand’s job is to create strong ties.

Organic communities on reddit or Discord naturally do this, but very, very few brands do.

After decades of culture built on weak ties, strong ties can feel risky. It’s hard to break away from the comfort of a one-to-many approach that is so common with weak ties, where a brand acts as the central voice in a brand community.

The experience is not dissimilar to a fandom gathering around a stage. Something that has immediate payoff and can easily be measured.

Strong ties, however, work very differently. A brand must continuously find ways to deepen relationships not between the brand and the people, but between and among the people themselves.

Harley Davidson has been doing this for a long time through events, gatherings, activations and destinations that deepen and strengthen how every member connects with every other member.

The community has become the brand, and people (users and non-users alike) understand that what you are buying is much more than a bike, and much more than belonging. They are buying the promise of connection.

Other luxury carmakers work in much the same way. A Lamborghini executive once told me that what they sell is a community, and the car is simply the price of entry.

Harley Davidson and others like it work very hard to deepen the connection between each driver. Strong ties are what drive the community brand forward.

Some of these rules may feel more like business strategy than brand strategy, but a solid brand is the basis of any strong business. The two are becoming increasingly intertwined.

How far is the distance between business and brand for Tesla, Apple or Meta? What about Coinbase, ByteDance or Instacart? Squint your eyes and the business and brand begin to look the same. To separate them is a mistake.

And that is what I mean when I say community has become the new brand. As community becomes the prime offering for many companies, it is also the forefront of how their brand is perceived.

Your employee community, user community, category community—all of these groups are becoming stronger signals of brand than ever before.

Be deliberate in how they are built and perceived.