Podcast Transcript

October 27, 2020

50 min read

Systems in flux: The hidden divergent forces shaping the next generation of brands, consumers, and capitalism

00:11

Jasmine Bina:

Welcome to Unseen Unknown. I’m Jasmine Bina. Today we have a house episode for you. Jean-Louis and I are going to be talking about something called, diversion systems. And it comes from an interesting place. So we’ve been recording this podcast for a few months now, and after every episode, we’ll have a conversation after the fact with the person that’s on the show, or we’ll be talking to each other. And we kind of have this conversation after the conversation where we ask ourselves, “Why are we witnessing the things that we’re talking about on this show? Why are these certain behaviors happening? Why are these certain opportunities opening up, and other ones closing? Why is the landscape shifting in this way?”

00:51

And it always invariably comes back to the same answer; if you really, really look at it, everything comes back to capitalism. And capitalism is really just a set of systems. The systems are theoretically simple. There are goals and there are incentives. If the goal of a free market is to make money, then the incentives are to make better products, offer better prices, create better brands people love, so on and so forth, so that you are able to reach that goal of making more money.

01:20

Jasmine Bina:

And in this simple definition of capitalism, where goals are aligned with incentives, it makes sense, except in some categories, it’s starting to go a little haywire. And those are the categories that we want to start talking about today. And in a series of conversations after this one over the next few episodes, where we’re going to talk about how we’re seeing it happen in certain verticals. Because in some places, goals might look like they’re aligned with incentives, but actually they’re not. And that is when you get divergent systems. Systems that start on a clear path, but then they start to split. And the bigger question really here is, when systems diverge, what happens to brands? And before we can get into that, we need to talk about what divergent systems actually are, on a more granular level. So Jean-Louis, this is your wheelhouse. Describe divergent systems for us.

02:15

Jean-Louis:

Yeah. The way I think you can think about this is, we’ve been running this kind of our economy, capitalism on an operating system, which is well over 100 years old by now. We haven’t really changed it at all. And so the way I kind of think about it is, you’re flying a plane at a slight angle, and over time, that plane is going to turn, and given enough time, and you might actually end up going back the way you were coming from. So I think that’s kind of where we are with a lot of these systems is, we haven’t changed the rules at play, and so the plane is just gradually turning. And so given enough time, a system that was designed for one goal might end up doing something completely different, because it’s not moving according to what the goal of the system is, it’s moving according to what incentive is.

03:00

So a really, really simple example of this is infrastructure. So when you think about infrastructure, the goal is obviously to support a city, support the environment with the tools that it needs, but the incentive is usually political capital. So a lot of cities are in desperate need of more bus networks, but that doesn’t really win an election. So you end up with a lot of rail stations that aren’t actually used that much. And so, you’re getting the goals really diverged from the actual actions that are happening in the system. Without getting political, if you look at political parties, the goal is to represent the interests of the public, but the incentive is influence. And usually influenced comes through capital. And so it’s not really surprising that you end up with a really strong duopoly, and you end up with massive polarization because it’s really effective at garnering capital and influence.

03:50

News, for example here. For a long, long time, it’s been running on the ad model. And with the ad model, while the goal of news might be to represent or communicate the events of the world, the incentive is attention. And so it shouldn’t be surprising if you follow that track. If you just think about where that’s going to go, fake news should be sort of expected when you’ve got a model that tracks towards attention. Algorithms that condition us to be kind of more outraged, more kind of sensationalized by these different things, those things should be expected. And so now, in response to that, you’ve got a lot of news sites that are becoming subscription platforms, and you’ve got others that are coming really pay-for-play. They’re changing the business model in response to that.

04:30

So you can see all of these systems as just, almost forget what the goal isn’t just think about what is the incentive that is keeping the system alive, and just imagine where that is going. And often it’s a really good prediction of what we’re going to end up with. And the problem is that we’re not able to fix the plane while it’s flying right now. And so it keeps turning, and we keep getting these systems that are kind of falling apart. And you right, now at least, with the infrastructure within capitalism, it’s not really changing much. And so it’s creating a lot of new demands.

05:05

Jasmine Bina:

So where else are we seeing diversion systems at play? And I think more importantly, why now? Because everything you described is clear as day, and it’s all happening at once. So why is it happening now, and is it even bigger than this?

05:19

Jean-Louis:

Right, right. So I think there’s two things that… Why now, is, if you imagine kind of your destination is straight ahead, and you’re just a fraction of a degree off, it takes a lot of time before the difference in direction becomes really visible. And so I think with a lot of these things, it has just taken a really long time, I think a perfect encapsulation of this is the healthcare industry. I mean, it goes without saying that it’s clearly diverged. But I think when you think about it from the point of view of like, what is the incentive here? It’s profit. Profit for the hospitals, but also profit for the insurance companies. And you’ve got a flood of private equity coming into hospitals to really dial this up. And so, it should be somewhat expected that in a system that doesn’t have the checks and balances it needs, and your insurance tells you, “Your deductible is higher this year.” “Your discount is higher.” But then they’re raising the prices.

06:13

You’ve got a system where there are no visible costs. It’s really not a free market anymore, because no one’s able to know the prices of things before they buy. And I think that’s one of the key problems here, is that when we talk about capitalism, it’s really, I think important to remember that a free market in and of itself does not want to stay free. What will happen over time is that through regulations, or through monopolies, people will try and close the door behind them. Businesses will try and close the door behind them. And in healthcare you’ve seen that they’ve created so many regulations that really make it incredibly difficult to compete, and incredibly difficult to operate as a free market where consumers have any level of choice. They’re not even the buyer really, the insurance company is, and so there’s so many levels of abstraction.

07:00

Jean-Louis:

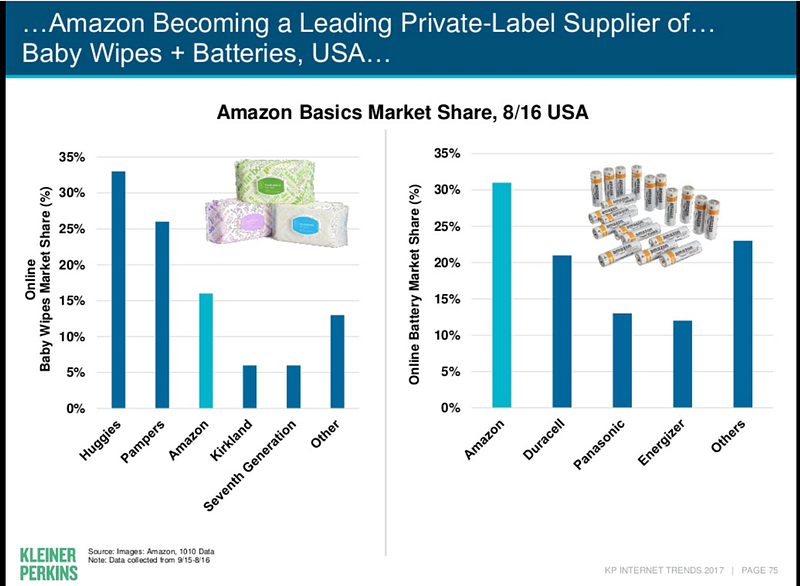

But then if you look at tech for example, they’ve done it in a different way. You’ve got these monopolies that literally block out the sun for competitors, and anyone who gets close. They just get acquired or just bought out. And so you’ve got so many ways in which the free market doesn’t want to stay free inherently. If you think about it as a system, it’s inherently unstable, and so you need those checks and balances. And I think in large part, we’ve kind of seen a failure to maintain the freedom of the market in so many different places.

07:30

Jasmine Bina:

Even if the market isn’t entirely free, in a world like this, where profit has to be the goal in order to survive, because the story is ultimately written by the victors. I mean, isn’t everything really divergent in some way or another?

07:45

Jean-Louis:

I mean, yes and no. I think a lot of systems do have divergent properties, but when a system diverges is when it’s really had enough time for that. I think what’s really interesting here is that we’re seeing the very, very, very beginning stages of new kind of infrastructure here. So, at the extreme end you’ve got cryptocurrency. And really, it’s less about the cryptocurrency itself, but more about organizational structures it enables. So people are starting to talk about DAOs, decentralized autonomous organizations, where you’ve got, essentially the rules of the organization are written in code, and anyone can kind of come and go freely and participate in this economy. And so we’re starting to see the very beginnings of this. Really, we’re at the infrastructure layer. If this was the internet, we’d be in the early 1980s right now. So this company Foundation. And they’re a great example of this, where they’ve created a market where artists, or any kind of creator can create goods that are linked to tokens, and people can buy and sell those tokens. And so they become an asset.

8:45

And so you can invest in an artist that you believe in, and what they’re doing there is, they’re creating a market. They’re creating an economy that gives ownership to the customers, and gives new kind of vehicles of capital and new vehicles of ownership for the creatives themselves. And so we’re starting to see different ways of organizing people. We’re seeing a rise in cooperatives in terms of businesses, we’re seeing a rise in equity crowdfunding for example, is another great way of people starting to think about, “Okay, how are we organizing around these things? How are we creating the incentives, and how are they aligned?”

09:51

And so it was starting to explore these things, I think were at the very, very beginning of maybe a Cambrian explosion of new formats for this. But again, I think maybe in five years, people would be talking about that, but right now we’re just at the infrastructure layer. So I think it’s coming, in terms of finding new ways, and I think what’s really important to hear is, how do you fix the plane in flight? How do we create a model that isn’t just, set and forget? Where we can actually tweak the rules of engagement as it goes? And I think things around decentralization and crypto are actually often new vehicles to do that.

09:57

Jasmine Bina:

So, I’m going to do something that you do a lot of times. Let’s test this idea by pushing it to the extreme. If we push this out to like 100, here’s what bugs me about this idea a little bit. And when you look at co-ops, decentralized systems where people can come and go and participate as they want, I think these things, you can understand how they work on a small scale, but the thing about a capitalist society, let’s just say American society is that people are driven by the fact that… This idea of rags to riches. The fact that you can do much better than your neighbor tomorrow.

10:30

And that’s why I feel people are so willing to put up with so much crap today, because they feel like there’s always a possibility that they can outperform other people. But these decentralized systems, crypto, the co-op idea, I think it kind of caps any one person having some sort of major breakaway success or taking more than their fair share of the profit, or whatever winnings, whatever you want to call it. I hope I’m not getting too abstract here, but it kind of feels like it’s going against human nature a little bit. Does that make sense?

11:06

Jean-Louis:

Yeah, I mean, what’s funny is that when you think about capitalism, there’s capitalism as a system, as the economics, but then there’s also capitalistic values. And I think that’s two very separate things that are almost always conflated for one another. And so I think certainly in this country, if you attack capitalism, it sounds as an attack on the values, and you kind of, you get lost in the weeds instantly. But I think there really are two different things. You raise a really good point. It was stress testing this. One of the challenges right now is that, if you take a cooperative for example, a lot of these business models can generate a ton of value for people, but maybe they only reach 10 or 100 million in terms of valuation for a company.

11:45

But you’re in an environment which you’re fighting against VC funding a lot of the time. And so you’ve got companies that, they strap $100 million to it, and say, “Hit the moon, or go bust. It doesn’t matter.” And so it’s kind of challenging because it’s stifling a lot of opportunity for these new businesses, because really the economics of VC is, either you’re a billion dollar company, or you don’t exist. And so it is a challenge though, but I think one of the really fascinating things is, the fundamental rules of capitalism might actually be changing kind of under our feet. And what I mean by that is that, for most of history, in my view at least, capitalism is really, in the way it existed, an enabled incremental advances. It really encouraged small improvements over competitors. You make a slightly better product, and you win the market, and someone else makes a slightly better product, and that’s generally how it worked.

12:38

When it came to massive advances in technology, that was usually left to governments. Because it wasn’t easy to get the capital to have something that takes 10 years, or maybe an unknown period of time of R&D to come across that breakthrough. But now with these trillion dollar companies that are emerging; Apple, Google, Facebook, Amazon, what’s starting to happen is, they have the means to make step-change advancements. It’s no longer incremental, as in for those few companies that are able to do that, they can invest in very, very, very long players, that may take an indefinite period of time, but when they come, they completely changed the market. We haven’t seen that yet, but you have to remember, all of this kind of a step-change advancements used to come from the public sector, with NASA developing all sorts of technology.

13:28

But now, with Google working on longevity science, with self-driving cars, with huge AI advancements, even like Neuralink for example, with Elon Musk creating a brain-machine interface. These changes, if taken commercial, would be potentially trillion dollar companies in their own right for each of them. But they’re completely owned by these trillion-dollar companies. And so I think we’re reaching a point where the rules of capitalism are changing. And I think that might impact our values. The story that you can go from rags to riches might not make sense in a world where the trillion-dollar company is literally sucking up all of the oxygen in the room.

14:07

Jasmine Bina:

Yeah. These trillion-dollar companies have the potential to create these step-change advancements instead of incremental change. Would you say they’ve also kind of… Obviously they’ve created the capital opportunity to do that, but have they also created the cultural opportunity to do that as they’ve started to take on a more prominent role in our lives, as they’ve become the new governments, which we’ve talked about so many times? Have they created an environment where we’re willing to let them create such huge changes, or we might not have allowed them so few decades ago?

14:44

Jean-Louis:

Yeah. I mean, I think it’s a really interesting question. One of the things I’ve been thinking about, and I don’t know how true it is, but it definitely seems to resonate with me is that, we’ve really changed recently in the way that a lot of these businesses work, where you’ve gone from the customer to the product. This was that line out of the social dilemma that everyone’s talking about. But I think it’s really quite profound, in the sense that when you hold the product, you’re not really a stakeholder in the conversation anymore. And I think that’s starting to happen in a lot of different places, especially when you think about AI. You’re the data point, you’re the data set. And so your opinions are far less valid.

15:23

And with these companies, they have so much capital to influence public opinion, they’re completely bulletproof from a kind of scandal point of view. They have massive operations. I mean, we should probably do our own episode about how the trust machines are designed to perpetuate trust, you cannot not trust them. And that’s literally the one thing that they need to create. And then they’re exceptional at that, and that’s what makes them so successful. So I think, in that regard, they’ve escaped that oven. And I don’t know if we have the power we think we do over them anymore.

15:54

Jasmine Bina:

Hold on, though. You watched the Social Dilemma? I did not see that. And I was very surprised at how much social chatter there was about it, because… Well, you tell me. There’s nothing in there that we don’t already know about, the ills of technology, right?

16:09

Jean-Louis:

No, but I think there’s one point that soundly stuck out to me. And that’s, when you think about Facebook and these social networks, it’s not that you are the products, but that the product is incremental behavior change. It’s getting you to behave ever so slightly differently, and when you think about that, that’s a big deal. And it’s kind of begs a really interesting question which is that, if you’re able to change society at large in terms of their views and their opinions and these kinds of things, maybe society is now a slightly divergent system, because you’ve got a new incentive at play, who knows?

16:49

Jasmine Bina:

Yeah, I don’t mean to be pessimistic, but I feel like we had kind of already knew that, I knew that. I think most people knew that. I’m guessing it’s only being presented it in a way that is a bit more shocking, but I feel like we knew that and we agreed to it, when we all started kind of giving up our privacy. I think that was the first, well we’ve talked about this before, I think that was the first signal that tech was slowly changing our actual behaviors, and the way that we related to each other…

Jean-Louis:

Yeah.

17:15

Jasmine Bina:

And the things that we were willing to accept. So, okay. Going back to that discussion. It’s easy to step away from this discussion and hear what you’re saying, and to say like, “Isn’t this just disruption?” So I’m going to ask you, isn’t this just disruption?

17:29

Jean-Louis:

Yes and no. I mean, I think… Really the story of this isn’t so much like this is creating the environment for disruption. This has created the social norm, I think that we now look to disruption as a point of trust. The point is that the systems have been broken enough that our trust in them have been broken. These aren’t authorities that we look to, and so we’re now looking for new authorities, and that’s forcing us into the arms of disruption. It’s forcing us to look to new players. And so when someone is disruptive, they’re sending a signal that we are not the broken system. We’re a new system. And I think we’re really willing to embrace that, because of this climate. So I think the disruption economy, if you could call it that, is because of divergent systems.

18:13

Jasmine Bina:

You’ve brought up trust a couple of times now, which I think leads me to the next question, which is, what does this mean for brands? Let’s bring it back down to earth. How is this changing the rules of engagement for our brands? What should brands be doing in response? Obviously, where does trust fit into this?

18:30

Jean-Louis:

Yeah, I mean, the way I sort of see this is that people are looking for power. They’re looking for control. A lot of the divergent systems, what’s happened is that they’ve gotten less control. In the medical industry, there’s no control. You cannot actually get a price before they do that. I mean, there was an example, it was on A16 podcasts. Could you imagine booking a plane, and they tell you, “We can only give you the price when you land. There’s just no way.”

18:59

Jasmine Bina:

And that’s a very soft example. I mean, there’s also just the power of being a woman, or a person of color. Trying to be heard in a medical system, it’s been documented so well, that depending on your race, or your class, or definitely your gender, doctors won’t take your descriptions of pain as seriously as they would somebody else, for example. Or they will be more likely to characterize your reactions or feelings as hysterical, over other things. It’s not just disempowerment and loss of control over technical things, like being able to track price transparency. It’s over like things that are also kind of dehumanizing.

19:41

Jean-Louis:

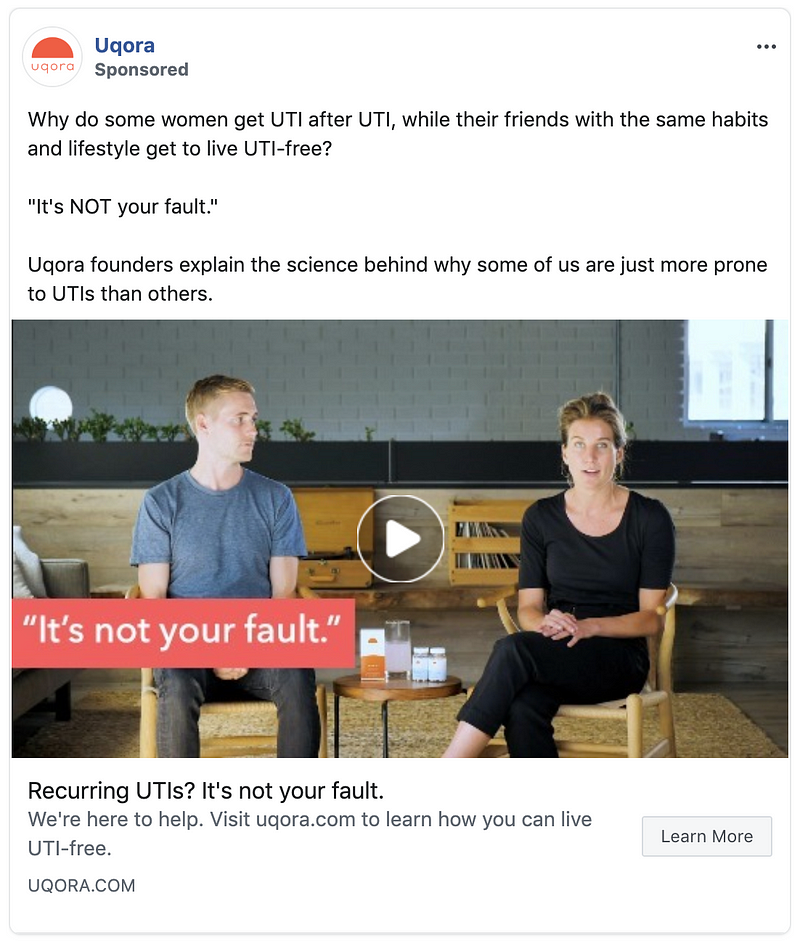

Yeah. No, I mean, it kind of sounds like, maybe it may be a small factor, but the numbers are insane. If you look at the numbers, these are very, very big deals. And I think just generally across the board, with these divergent systems, you the consumer, you the individual, generally lose power in all of these conversations when it comes to political bodies. You’ve lost power because it’s about the capital and the influence. And for most of these systems, you become the product. And so in terms of what brands can do, it’s giving people a sense of power back, and designing an incentive that really aligns with that. Creating the ability for some kind of value generation for your customers, to be part of your incentive as a business. So there are different ways that you can do that. The most tangible one is building your business around a cause.

20:29

So, I mean, you’ve got like sustainability brands as a baseline, or even a company like Patagonia. They are successful on the back of building a community around environmental advocacy. And so, if that is successful, or rather the success of their environmental advocacy has a large impact on the success of that. And so even though it was a private company, their incentive might be profit, that’s largely driven by their ability to provide a meaningful impact and create value. And so I think as a brand, when you’re thinking about operating in this environment, you have to think about, “How do I bring the incentives of my business, which are almost always going to be profit ultimately, how do I align those as best I can, with value creation for my customers? At a very fundamental level, what can we do?”

21:13

And so another example is creating your brand around a perspective, or sharing a voice, or creating a community. These kinds of vehicles are creating value for your customers, but also if done right, can generate a lot of profit for you as a business. And so it’s really about thinking about where are we creating value, and how can we align our incentives around that? I think fundamentally at a systems level approach, that’s the best thing you can do. Because really, again, we’re looking for disruption because we’re looking for power, we’re looking for control again. We want to feel like a stakeholder in all of this. And when you create value like that, you’re doing that for the customers.

21:51

Jasmine Bina:

Yeah, and when you say trust, that’s super interesting because, you can talk about having a cause, you can talk about creating communities where people feel like they belong, you can talk about corporate social responsibility, or providing value through really wondrous experiences. You can talk about so many different things and lenses that brand touches. But if you go and re-examine them again, and say, “Is this creating a source of trust for people?” Not, “Do they trust our brand?” But do they feel like they are in a system that is trustworthy? That gives them that control back? I feel like that changes the answers a lot. And a lot of brands would be very hard pressed to actually answer those questions in a way that makes sense in a non-divergent system. I mean, let’s be honest here. This sounds hard and probably not easy to scale, right?

22:44

Jean-Louis:

Yeah. I mean, yeah. Ultimately it’s hard and it takes a lot of serious decisions to get there. But I think you sort of touched on it in the sense that, real authenticity nowadays… I think people are so fatigued by lip service, that you have to have authenticity at a systems level essentially. And that’s really… Almost what I’m talking about here in terms of value creation is that you need to design your business in a way that it authentically creates value for people. Like that is part of the incentive. It’s the model, it’s the expectation that’s been set. And so I think that’s kind of what we’re demanding of these businesses. You can’t say these things without backing them up with actions now. It’s becoming far more sensitive to these things, and far more aware of the actions businesses, take when leadership fails, even if it’s just the company culture. That’s a big deal now in a way it wasn’t before. So the climate has changed, our tolerance for these things has really changed around it.

23:41

Jasmine Bina:

So we’re kind of talking about this already, but I want to go deeper. So how is this changing consumers and culture? Or, I don’t know if it is the chicken or the egg. Did consumers and culture change, and now it’s changing business? I don’t even know if we need to ask that question, but how are these parts of the equation being changed?

24:02

Jean-Louis:

Yeah, I mean, it’s definitely kind of everyone’s been changed at the same time. I mean, this is kind of such a slow moving vehicle in terms of divergence. Again, a lot of these things have been in the works for 100 years or so. It takes a lot of time, but I think there’s a few trends that we know are happening. We know that people are trying to circumvent the broken system. Again, kind of going back to the medical industry, it’s so clear here that we are looking for new ways and new places that we can fulfill those needs. And so it shouldn’t be any surprise, in a world where you can’t guarantee your wellbeing through the health care industry anymore, the trust isn’t there. And so obviously you rely on it when you need to, but that’s probably one of the contributing factors to why wellness has become so strong.

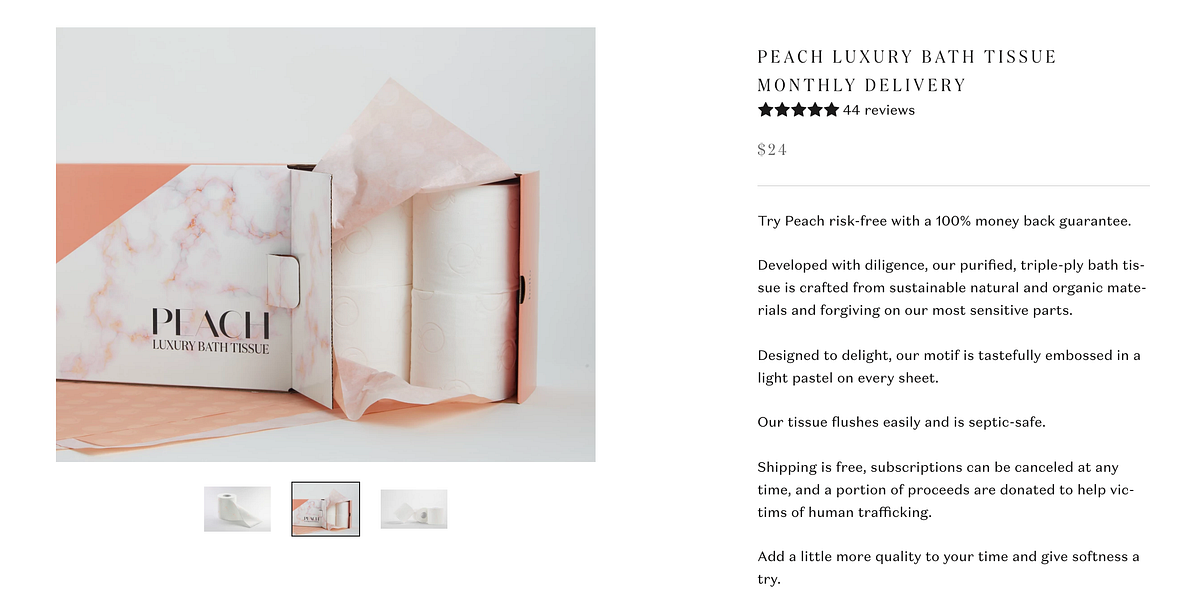

24:44

We’ve become massively disenfranchised with healthcare, and so we are looking to new places, to new ways of fulfilling those needs. And so we buy wellness products, we follow wellness influences in a way it’s… I think you have to see this from a mental category point of view. We are seeing this in the same bucket of, “This is my health. And so I’m taking care of my health in new ways now.” And the divergent system has kind of forced us into these new behaviors. But I think the subtext here, which is interesting and maybe concerning is the fact that this usually trickles down from the top. You have very premium offerings come in, and they grab the capital, and they take that opportunity, and it’s mostly with more affluent customers.

25:28

Jasmine Bina:

Yeah, I know. Yeah, I know exactly what you’re talking about. I think of Parsley Health, when you talk about this. And for the record, I love Parsley Health, I’m a Parsley Health member. I’m not even going to say patient, I’m a member, because it feels like a club, and you get great healthcare. But man, does it cost money! And they don’t accept insurance. You get great healthcare, but at the same time, you kind of… They put a lot of emphasis on design and creating very comfortable spaces, and a lot of, I think, empathetic healthcare is about solving a design problem too, design from the spaces to the actual patient flow, to how you interact with your doctor, all things which they’ve innovated on.

26:11

Jean-Louis:

Well there’s trust design. I mean, it goes back to it. The pastel’s really a code for trust. Code for, “We’re not the old way of doing it.”

26:20

Jasmine Bina:

That’s a really good point. Because it’s easy to look at that and be kind of skeptical and be like, “All right. Are these beautiful colors and rattan furniture in these third spaces that they’ve created, and the kombucha on tap, or whatever it is, is that really going to solve the world’s medical crisis?” But you’re right. It does solve a mental barrier that we have right now, around just how the experience starts when you walk in those places.

26:45

Jean-Louis:

Yeah, I mean, it’s happening in all over the place. Again, going back to news, with these membership platforms, they get progressively more expensive. I mean, even if you look at a Sub stack in these kind of more boutique niche things, you can pay a lot of money to get incredibly high quality news and analysis of the world. And so you can see the world in a different lens if you have the capital. What’s happening here is social stratification. Is you’re getting society is broken up into different tiers, and eventually these things might trickle down, and you’ll get consumer access for the mass market.

27:17

But I think a great barometer of, is something divergent happening here? Is society getting stratified? Are different levels, different tiers of society able to have very different experiences, and their needs fulfilled in different ways?

27:30

And so without divulging too much, I think the conversation about capitalism versus socialism is really, where do we find it acceptable to have social stratification? Is it okay to stratify people’s healthcare? Or people’s education? Or people’s infrastructure? That’s, I think in my eyes at least, a big part of the conversation that people don’t realize they’re having is, where is it okay to have different levels of service for different people? Where is it a right to have everyone have a baseline? And I think that’s really what we’re talking about, because socialism really is just capitalism with a slightly larger welfare system.

28:07

Jasmine Bina:

Oh, be careful what you say here. It’s election season. I would not throw those words around lightly. But I mean, I get what you’re saying, taking the socialist piece out. How we choose where we’re willing to accept this kind of stratification, is a very, very direct signal of what a society values in different ways. Is that what you’re trying to say?

28:30

Jean-Louis:

Well, yeah. I mean, it goes back to this point about, it’s not really about capitalism, it’s the bad capitalistic values here, in terms of where we choose to draw the line. And you can see that, because other countries are also capitalistic in terms of that model, but the values are slightly different. And so they draw the lines in different places. And I think it’s so it’s so powerful when you delineate values from the actual economics, because they’re two very separate things. “What do we accept?” That’s really the question there.

28:58

Jasmine Bina:

Can you give us some examples of how it’s different in this country versus other countries? That will really, I think, illustrate what we mean by this.

29:05

Jean-Louis:

Well, I mean education is a great place to look. So there’s a big conversation right now about making university free, because university or college is no longer… I mean, really it’s a baseline now for the workforce. I mean, it’s been a long, long, long, long, long time since high school was the benchmark.

29:23

And so really, by making that free, you’re expressing your values and saying, “This is the benchmark for society, and this is what equal opportunity should start as a baseline.” And obviously if you’ve got more money, you go to private schools, whatever. And so, I think in Germany, university is free. Or at least at a certain level. And a lot of countries are looking at that and starting to say that, “Okay, higher education is free up to this level.” And that level is gradually rising in a lot of places. But I think it’s a very transparent way of seeing the values at play there.

29:55

Jasmine Bina:

So where do you predict the next set of diversion systems is going to emerge? We’ve mentioned the obvious ones, education, politics, healthcare. Where’s the next set going to come from?

30:09

Jean-Louis:

Well, I definitely think we’re going to see a subset of play in terms of mental health. I think that’s a whole space that there really isn’t even much of an industry around it right now, but it’s such a big thing. And especially with COVID, I think we’re going to see a lot of social stratification around that. That if you have money, or with this case shape recovery that we’re talking about, you’re going to have a very different experience. But if you have money, you can really take care of your mental health in different ways.

30:32

Jasmine Bina:

But isn’t that already true though? Are you saying there’s going to be even more ways to circumvent?

30:37

Jean-Louis:

Oh, far more ways to circumvent. But I think especially when it comes to childhood. And children’s experiences of COVID, in terms of like, it’s a huge, huge impact to have a lack of social interactions for such a long period of time. And that the ramifications of that, you’re going to have two very different classes of people from out of that.

30:54

Jasmine Bina:

Oh you’re already seeing it? Kids that have a pod, and kids that are doing remote learning. Or risking their health going to school, or whatever. I’m not dogging anybody’s personal decisions, whether they send their kids to school or not, but the fact is that some kids have a choice and other kids don’t.

31:10

Jean-Louis:

Yeah, I think, I mean, in my eyes, what’s the most interesting is, we’re seeing very, very, very quiet signals right now, of an infrastructure change. As I was saying before about decentralized autonomous organizations, and these kinds of things. We’re starting to see a new layer of infrastructure that creates new types of incentives. New ways of organizing people around these incentives, and potentially the chance to fix the vehicle while it’s moving. Ways of updating these incentives and these models in play. Those things are incredibly exciting, and there’s now such a demand for it. Because these systems aren’t really working for us. Again, it goes back to that question of, are these systems going to be stifled by hyper-aggressive models like the VC model right now? We don’t know, but I think what’s really exciting to me is these infrastructure changes.

32:04

Jean-Louis:

If you’re a brand in the next three to five years, this conversation is very quiet now, but you’re going to see it get louder and louder and louder, just like the internet. Suddenly it was all there, if she wasn’t paying attention. And so I think that you have to start thinking about this at a systems level. You have to think about your business as, “Where am I creating value, and where are my incentives?” Because if you aren’t all careful, you’re going to wake up one day, and there’s going to be a new model that is completely outpacing the way you can operate.

32:31

And again, these things are getting more direct. With creators, now with these direct relationships with Patreon and Sub stack, and you no longer have to go through mediators. If you look at the media industry, right now it’s mostly rent seekers. If you look at Spotify and YouTube and all these kind of aggregation platforms, all they’re doing is kind of surfacing it. They’re rent seekers in the sense that they’re not really creating true value themselves, they’re extracting value from everyone else. And so all of these models are emerging, where it’s a direct relationship, it’s direct engagement. That’s creating a new norm for people. That’s creating a new behavior and a new expectation of saying, “I don’t need to go through these central circles.”

33:09

Jasmine Bina:

Well, also it creates that sense of trust and control that we know people are seeking too.

33:13

Jean-Louis:

Exactly. I mean, it all points to the same thing. There is a new set of behaviors and values coming out of this, as a response to the divergent systems. And if you can speak to those, if you can fulfill those, and you can behave in those kinds of ways and create direct relationships and access without mediation, I think there’s huge opportunities to get. I mean, really quite profound ones, because we’re talking about systems here. It’s not even industries, or categories, or anything like that. This is the fundamental gears of how we service our needs as consumers.

33:48

Jasmine Bina:

So if you’re a founder or a brand owner, other than the obvious question of like, “Are my goals aligned with my incentives?’ What can you ask yourself, to really understand where the divergence is within the systems that you operate?

34:03

Jean-Louis:

Yeah, I think, I mean, the first thing you have to do is understand where your consumers are, in the context of what you’re offering them, and in the context really of the needs that they’re getting fulfilled. Because again, if you look at wellness, the needs of taking care of my health, that was what was at play in terms of pushing people out of the health care industry, and into the wellness industry.

34:23

Jasmine Bina:

And I think… This brings me to another point. A lot of times people don’t even know how their consumers define the products. What does health mean? Well, health stopped, for a huge faction of people, it stopped meaning, not being sick, and started meaning living to your most extreme physical potential. I mean, just the fact that their definitions change, meant that the system was starting to diverge, because now the goals and incentives are not the same for you as they are for your users, right?

34:57

Jean-Louis:

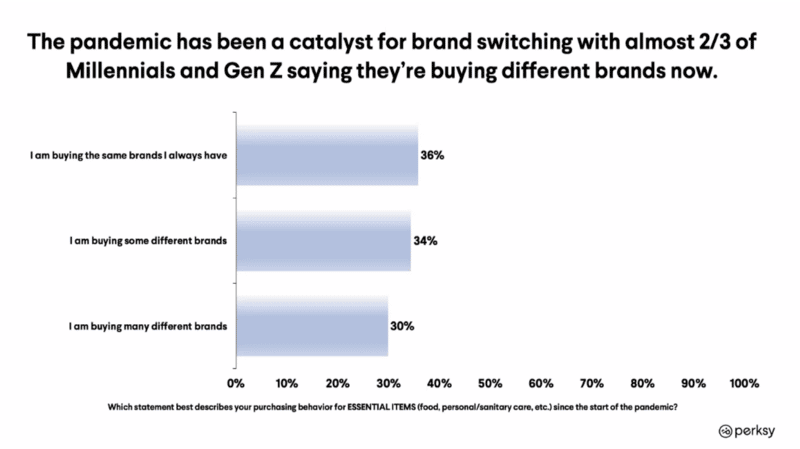

Yeah, yeah. For sure. I think we’re seeing a lot of those changes there, but the way you have to look at it is just at the very, very basic needs viewpoint. Because that really is universal to these things. And so it sets the context of engagement. And so understanding, where are people moving? Because there’s a lot of foot traffic right now. People are really… They’re moving away from industries and moving to new ones. We have this appetite for disruption, because we were looking for authentic, trusted relationships. We’re looking for these new standards of engagement now. And so you have to look at the needs to understand where the foot traffic is going. Where are people moving? How is this consumer base changing? Because again, I mean, right now it’s mostly early adopters. And it’s mostly this top tier of consumers, premium luxury consumers, that are very affluent. And so it doesn’t seem like… Maybe it’s not a huge market right now, but you’d be missing the signal.

35:51

Jasmine Bina:

Yeah, it’s kind of funny. I don’t want to simplify anything that we’ve described here, because I think it’s pretty profound, what you’ve kind of summed up for us. But you could kind of boil it down to something that you and I have always talked about with our clients, which is, you might have a vision, and you might want to know what you want to create in the world, whether you’re a startup or the CEO of a public company, we work with both. But it kind of doesn’t matter. What matters is, what your consumer wants, where they believe they’re headed, and what they’re willing to let you do, in order to make that happen with them. To the point that when we do all that research, when we really start to understand those triggers, when we really start to create a very rich picture of the value systems that these people have for themselves and how they operate in the world, and the roles that they play, it’s kind of irrelevant what the founder actually wants.

36:47

The best founders, which fortunately we always get to work with, are the ones whose desires have actually deep down, tapped into an emerging wave of change in the culture, but they didn’t realize it. They didn’t mean to necessarily articulate it, but they tapped into the much deeper needs of their audience. So again, not to simplify what we’ve described here, but a really easy guardrail is to just make sure like, “Am I really, really paying attention to what people want?” Because a lot of times, what brings people to your brand, is not what keeps them there. They might come because they need to buy something, but they stay because you’re providing them with something different than just the product. I think the smartest brands understand that. And I think that’s kind of what we’re talking about.

37:34

Jean-Louis:

Yeah, for sure. I mean, it’s all just systems of value. And a lot of the time you just get lucky, you just happen upon, without even knowing. A lot of the time, people don’t even realize the actual value they’re providing for people. But ultimately, you can kind of strip away everything else, and the success of business can be predicted by its ability to fulfill value for people.

37:57

Jasmine Bina:

Right. Well, I think that was a great discussion on diversion system. So after this, we’ll probably do another house episode at some point, just to wrap this all up. But we’ll be talking to other people in different verticals, about how diversion systems are creating new brand opportunities in their categories, so we can really get a rich understanding of what this divergence actually means.

38:18

And like anything else, I personally find that I learn a lot more when I understand it in somebody else’s industry, than when I understand it in my own. Because it forces you to really kind of let go of your biases, and see an idea mapped in onto a different space. And once you understand the actual truths, then you can start applying it to your own. So we’re hoping that as we talk to different people, we bring that same value to the people who are listening. So Jean-Louis, thank you so much. Another great house episode, and we’ll talk to all of you guys soon.