When Moonjuice was founded in 2011 by Amanda Chantal Bacon, it was easy for people (like myself) to dismiss it as out of touch branding. The company’s hero product, Sex Dust, was an adaptogen-laden powder that promised support for “your sex life, sexual arousal, or sexual performance” with a hefty price tag.

For the uninitiated mainstream, Sex Dust and the many other cosmically branded Moonjuice products like it, seemed like ridiculous promises for ridiculous problems.

What I didn’t realize at the time was that Bacon had tapped into a wellness signal that the rest of us couldn’t hear yet. She understood that a new form of spiritual wellness, which combined performance, supernatural leanings, and alternative health was on the cusp of our collective consciousness.

That spiritual wellness was invisible culture, and when it surfaced, it became a part of our shared reality.

Every trend starts as an anomaly: a deviation from the norm that may look like an outlier at first, but actually signals a widespread change that is about to come.

Companies that spot cultural change before it becomes visible will always have an advantage not only in brand strategy, but also in innovation. The most valuable strategies and innovations have always been predicated on a prediction, and the only predictions that matter are the ones that tell us where culture is headed.

Invisible culture will tell you where people are willing to be pulled. It will reveal what direction they’re inclined to move in, opening a channel of new and viable opportunities that didn’t exist before.

In their article, “The Power of Anomaly”, authors Martin Reeves, Bob Goodson and Kevin Whitaker explain that finding these invisible changes means looking in the right place at the right time:

“To take advantage of emerging trends, companies must identify them when they are embryonic—not purely speculative, but not yet named or widely known. At that stage the signs will be merely anomalies: weak signals that are in some way surprising but not entirely clear in scope or import.”

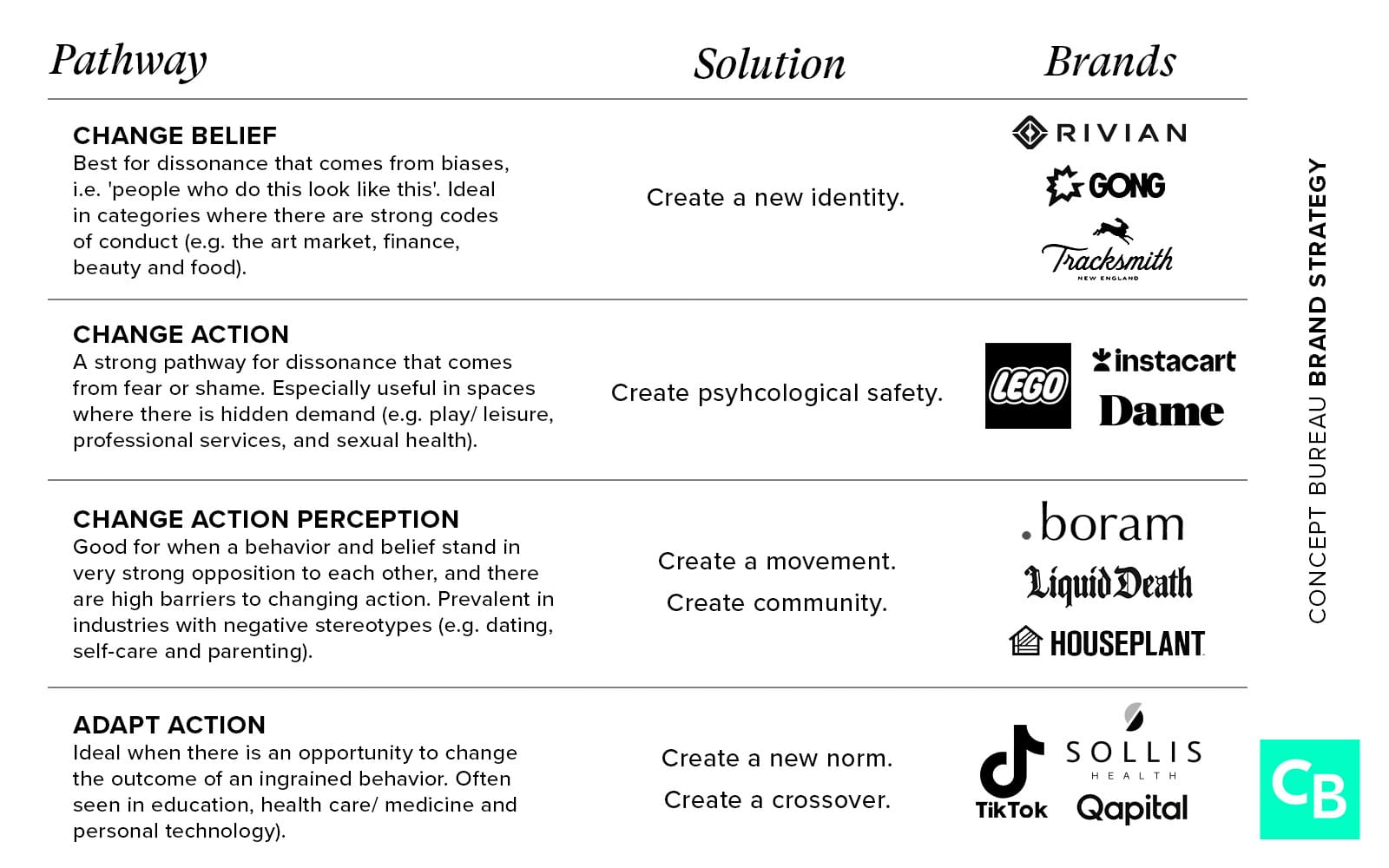

The kinds of anomalies that matter in strategy are the ones that show us how people are changing, and this is what my team at Concept Bureau focuses on in our monthly Brands & Outliers meeting. Our goal in that meeting, and throughout all of our work, is to look for changes in three main dimensions: how people feel emotionally, how people behave personally and publicly, and what people believe.

Emotions, behaviors and beliefs will always lead you to the heart of invisible culture. When any of those three things start to shift, there’s likely an anomaly worth paying attention to.

But how do you find these bleeding edge anomalies and shifts in the first place? The inconvenient answer is that it takes experience. The more you research, pay attention, and learn to think like a strategist, the more you will develop a sixth sense for spotting it.

However, there are some hotspots along the landscape that tend to house invisible culture more than others. They provide dependable signals in categories full of noise, especially in places where there are many stakeholders or competing narratives:

- Where categories intersect

- Strong tie communities

- Dissenting voices

Each of these places reveals different truths, but all of them will give you a pulse on how people are evolving and how they are willing (or wanting) to change.

When a brand understands that, they have permission to create a whole new future for their audience.

#1 Look at the intersection between categories.

The border between your category and another is usually where users are evolving the most. The changes that happen here tend to be step-changes in how people behave. It’s where we see many new norms and behaviors first emerge.

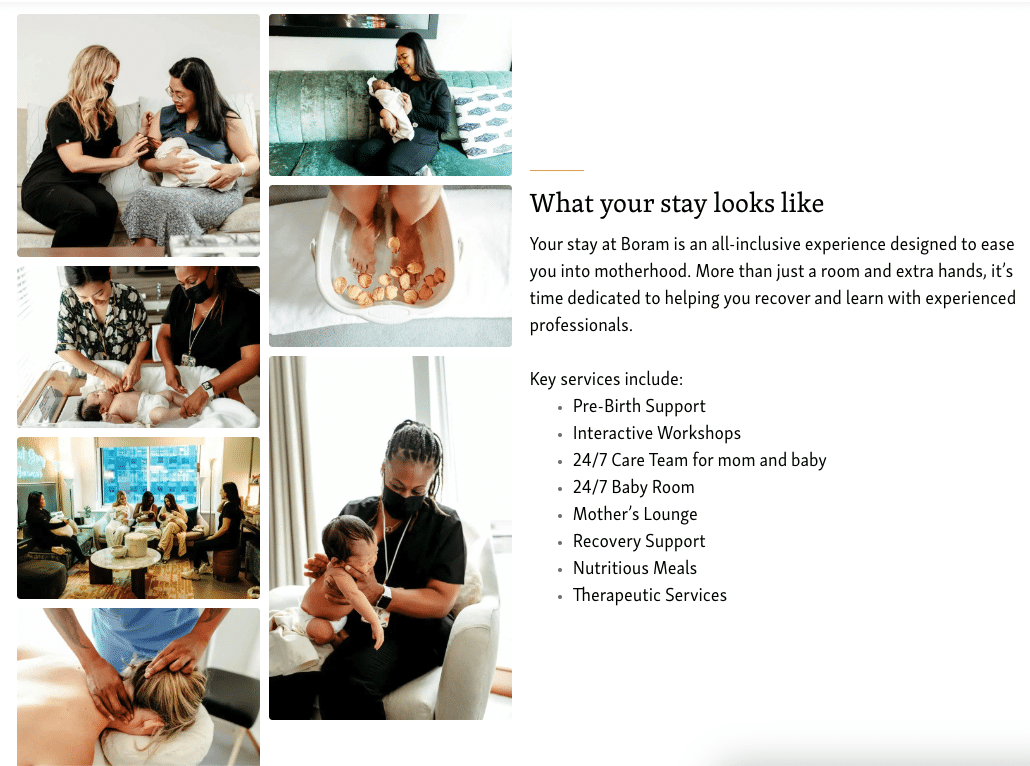

If you look at the intersection of healthcare and parenting, you see brands like Boram Care (postpartum retreat for moms), Genexa (clean kids medicine), Slumberkins (emotional learning tools for children) and a whole host of influencers, communities and private schools focused on alternative development styles.

All of these point toward more thoughtful care for children, but that’s obvious.

Spotting the real trend requires you to zoom out and look at how people are changing among all of these examples, and when you do that, what you find is a redefinition of the parent.

Parents have become increasingly intuitive about how they raise kids. They don’t look to grandparents for advice, they don’t subscribe to just a single ideology, and the few experts they do wholly subscribe to are usually the ones going against the grain.

Parenting is less about doing what is accepted as right, and more about doing what feels right. Being a parent may have once been an act of well-trodden routines and pathways, but it is increasingly becoming an act of defiance, in both the big things and the little things. Many of the choices a parent makes are in resistance to something they don’t agree with, in exchange for something that is more aligned with their intuition.

That insight creates new room for new innovations, brands and experiences.

You can do the same at the intersection of any other two categories. It will often be a leading indicator of what is to come.

#2 Watch for changing emotions in strong tie communities.

Weak ties historically allowed us to extract value from the peripheries of our networks (think LinkedIn, Instagram and Twitter), while strong ties extract value from relationships at the center of our networks (think Patreon, niche Discord groups, online affinity groups, and the proliferation of like minded living communities like Latitude Margaritaville).

While weak ties have been the underpinning of social innovation for the last two decades, strong ties are starting to emerge as the dominant threads of our social fabric.

Strong tie communities are a valuable place to look for the future because they’re typically where culture is most expressed and engaged with. When emotions and feelings begin to turn in these spaces, culture will soon follow.

We’ve seen this with many of our clients, including strong tie communities in beauty, self-care, education and dating. When emotions started to change in these deep, personal spaces between people, we knew a shift was coming. Emotions shift before people even have the words or the ideas to articulate the change they are experiencing.

Nearly all beverage industry experts attribute the strong rise of non-alcoholic adult beverages to people being more health conscious, more sober-curious, and more willing to substitute alcohol with cannabis. Gen Z goes so far as to call alcohol “Boomer technology”.

The vast majority of research reports cite these same factors over and over again, but they are missing an important change in people’s emotions—a change that can only be seen in the corners of strong tie communities—that explains this phenomenon much better.

People overall are gathering in more thoughtful ways. They are choosing connective activities like experiential dinners and holidays with chosen family. They’re playing board games and jumping in adult bounce houses. They still gather to drink, but when they do, it’s less in bars and more in the intimacy of their own homes with friends.

They seek more connective social experiences than before, in no small part due to COVID, and aim to engage with others more meaningfully. They want shared experiences that require them to be wholly present. One look at the fanbase that has formed around author Priya Parker’s book Art of Gathering will show you how far people are going today in order to reinvent the common meetup, party or hang in order to emotionally connect.

These more thoughtful gatherings require us to rethink the concept of alcohol. Yes, we want to be healthier, but we also want more fully immersed, human-to-human interactions.

This is where many alcoholic and non-alcoholic beverage brands will make the mistake of a shallow gesture, believing that adding adaptogenic ingredients or an organic label will be enough to capture this changing mindset, when in fact the trend in lower alcohol consumption is much bigger than obvious health reasons.

Emotions are taking a sharp turn when it comes to the ways we gather. We come together for different reasons now, and with very different expectations. We expect to change or be changed through our encounters with others. We expect to go deeper and feel something personally.

Where drinking may have once been a vehicle for helping us lighten up or numb out, it is now a vehicle for settling down and plugging in.

That’s a future signal that any brand—alcoholic or not—can do something interesting with.

#3 Listen for dissenting stories.

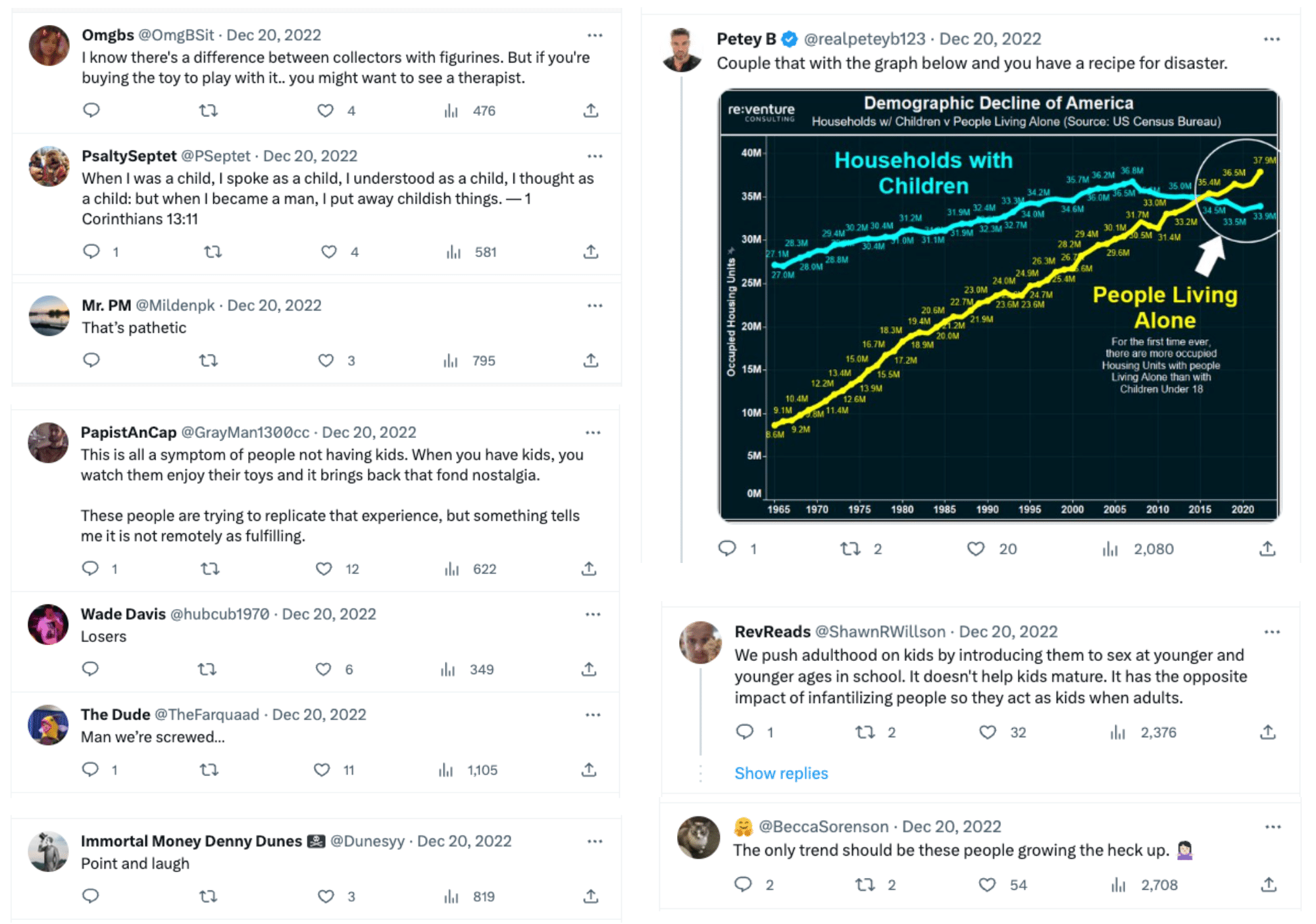

When an idea or story is widely accepted, pay attention to the quiet voices that dissent. By the time that idea is openly resisted, it will be too late to take advantage of the change.

For every story, there is an opposing story that will tell you just as much (if not more) about the direction of invisible culture. Find the unheard stories that counteract our accepted beliefs, find out who is telling those stories and how they are telling them.

When we developed the brand strategy for AI consultancy Prolego in 2021, they faced a unique problem. Their B2B clients wanted to embrace AI in their businesses, but those clients’ B2C customers shared widespread fears of AI’s potential risks. C-suites coveted the AI prowess of TikTok, but feared the AI backlash of Cambridge Analytica.

It was a different time, before chatGPT, when Alexa smart home assistants and Siri enabled devices were the extent to which most people experienced AI in their daily lives. But even with only these rudimentary forms of AI, the public’s opinion was largely informed by dystopian movies, clickbait headlines, and economic insecurity.

In our research for Prolego, we discovered a quiet, invisible group of people we called “AI Natives”, and turned our findings into a report called AI Natives Among Us. That report demonstrated a very early signal of invisible culture that has only just come to fruition in the past few months.

Just as the digital natives who came before them had an innate ability to navigate the internet, AI Natives were defined by their ability to build relationships with the AI around them. They were not merely AI users. They were connected to AI in a way that allowed them to shape AI tools for their own needs, willing to invest in molding AI for their unique way of life.

The widely accepted mainstream story of the time was that AI was a nefarious “other”, but the dissenting story of this audience was that AI was very much a technology that belonged within the human experience. AI Natives didn’t want to see technology, they wanted to feel it, and that distinction perfectly describes the difference between the apps of yesterday and the AI platforms of today.

One AI Native told us, “We’re going on vacation in a month and we’re actually packing my Google Home because I’m so used to telling it things.” A Director at a Fortune 30 healthcare company said, “In a hundred years from now, there probably will be no internet or smartphones, but there will certainly be AI.”

Most interestingly, after hearing about a company’s investment in AI, nearly half of adults under the age of 45 were more likely to believe the company positively affected society and cared about its customers. AI had a profound halo effect on the perception of a brand among AI Natives.

Their story has quickly proven to be our trajectory. There is still cultural uncertainty and fear, but the once-dissenting story of the AI Native is a clear signal of what is to come.

The anomalies of invisible culture require us to approach everything we see with an open and nimble mind. The fact is culture is always changing at the edges, always moving in a new direction, and never in a straight line for too long.

Every brand and innovation that mattered came from an understanding of these changes.

Not every anomaly will be a true signal, of course, but if you pay attention for long enough, you will start to gain a sense for the kinds of outliers that will regress back to the mean, and the kinds that will change it.

Keep searching in the places where invisible culture tends to pop up, get a strong feel for how new emotions, behaviors and beliefs bubble at the edges, and gain an advantage in the marketplace.